Where boys learn to be men

Men Can Stop Rape's MOST Club uses lessons in healthy masculinity to curb sexual violence against women

Katie Hiler • January 12, 2013

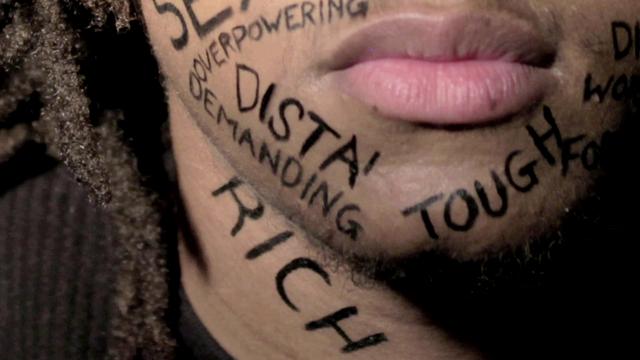

A PSA video for Men Can Stop Rape sends the message that men can be strong without being violent. [Image Credit: Richard D. Kinnard via http://vimeo.com/41292937]

It’s around 11:30 on a Wednesday morning, in a dimly lit classroom on the fourth floor of Brooklyn Collegiate High School in Brownsville, N.Y. Fourteen teenage boys are gathered for a meeting of MOST, or the Men of Strength Club. The conversation has been interrupted to pass around some snacks. Peter Wehye, the school’s physical education teacher and facilitator of the club, redirects the group to the question he posed before the interruption, about whether or not a man who cries should be considered a “punk.”

“I’m in front of my lady, right? And we goin’ back and forth, right? And she slaps me. And I start crying.”

Reactions are immediate and varied. “Oh yeahhh,” says one boy. Another wants clarification, “You boo hoo crying?” The young men shout over each other until one voice cuts through the din. “There’s certain things you gotta cry for and certain things you gotta take to the heart and just deal with,” says one of the older boys leaning across his desk.Wehye is trying to get his students to think about how society informs them of what it means to be men, and he’s been waiting for an opening just like this.

“So here’s the thing,” Wehye says. “Who decides what we should take to the heart?”

The MOST Club, a middle- and high-school based sexual violence prevention program run by the Washington-based non-profit Men Can Stop Rape, aims to address sexual violence by getting boys and men to confront deep-seated ideas about masculinity. Its mission reflects a growing consensus in the U.S that violence against women is rooted in rigid gender norms and in the way boys and men are socialized. The MOST Club uses a strategy of intervention based on social norms theory, which suggests that sexual violence occurs because men see other men support or encourage negative gender stereotypes and physical abuse. Its approach to sexual violence prevention involves identifying healthy expressions of masculinity that do not center around violence. Exactly how well MOST and similar programs are working is still uncertain – getting good data has been difficult – but the program’s designers and some prevention experts say they can see evidence of its success.

For the past few years the strategy of engaging men in sexual violence prevention has enjoyed both national and international public support. But the recent rape and death of a female student in New Delhi, India is a reminder that the struggle to end violence against women is still ongoing and cannot be won by ideas and support alone – sexual violence prevention programs need to be successful to really make an impact.

And of all the programs prepared to tackle this issue, the MOST Club program is an appealing option, in part because of its positive message. “A lot of times [it’s] been framed as telling men what not to do, and how not to behave and who not to be,” says Patrick McGann, director of strategy and planning with Men Can Stop Rape. “But you’re not really helping them think about who they want to be, how they want to behave.”

To do that, MOST Club members participate in conversations and exercises that help them identify ways in which they are being informed by popular culture about what it means to be men. For the past few months Wehye has slowly been taking the class through season four of HBO’s “The Wire,” which is set in an inner city high school much like theirs. Wehye says watching The Wire is a step up from the hypothetical situations he brings to the class because the students are able to watch characters react to a situation as its happening. “They are talking about what’s on screen, but it’s really what they see every day,” Wehye says. “But it’s easier to say ‘Joe’s making a wrong decision’ instead of saying ‘I made a wrong decision.’”

Stan Hall is a veteran MOST Club facilitator from Baltimore who is now a regional coordinator for the program. He recommended the club to the principal of Brooklyn Collegiate and acts as a mentor to Wehye. “This curriculum is very solid,” Hall says as he watches Wehye take answers from the students and write them on the board. “Without any effort, everything that’s happening, every comment they are making is exactly what I anticipate.”

Eventually Wehye will bring the topic of sexual violence prevention into these conversations about healthy masculinity. He will help the students label actions and behaviors – whistling at a woman, calling her a “bitch,” physical violence – on a continuum of ways men can be harmful to women. “It’s really about embracing your own power and understanding how to use that power in a really positive and constructive way,” Hall says. “And the ultimate misuse of power against women is rape.”

For Wehye, progress with his students can be slow. A few weeks ago, he threw out two names to his students for comparison: Barack Obama and rapper 50 Cent. Wehye asked the boys, “Who’s the stronger man?” A raucous discussion ensued. “Nobody could get over the fact that 50 Cent was shot nine times and handles his own business,” Wehye says, incredulously. “And this is why he’s a real man.”

Whether progress can be measured at all is still an open question for sexual violence prevention programs like the MOST Club. Francine Perry, director of community services at New Hope Inc., a sexual assault center in Massachusetts, says that measuring the effectiveness of different prevention strategies isn’t as simple as determining whether a new pill lowers your blood pressure. It requires consistent program delivery, reliable indicators of success, and long-term follow up – things most non-profits don’t have money or time for. “That’s our big struggle,” Perry says, “but yet we’re charged with finding a way.”

These same limitations make it hard for McGann to definitively say how well the MOST Club strategy is working. “We’ve seen some success in evaluation research with the club indicating stronger likelihood to intervene” when witnessing gender based violence, he says, “but it is a challenge.”

In 2009 researchers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention co-authored a supplement in the journal Health Promotion Practice on the topic of sexual violence prevention programs. In a study that evaluated the MOST Club, the CDC team identified a number of the program’s weaknesses, including the need to ensure that changes in knowledge, attitudes and behaviors would be sustained in its members after they graduate. The CDC also suggested the club enlist the help of principals, teachers, organizations and community groups in teaching its lessons about gender based violence.

The club has taken at least some of these recommendations into consideration, according to McGann. It now involves those who finish the program as mentors to those newly entering, and McGann says the organization is starting to compile data that will tell them whether membership affects school attendance and grades – numbers they would be able to show principals and administrators to garner their support.

David Lee, director of prevention services for the California Coalition Against Sexual Assault, believes the MOST Club has the potential to curb sexual violence here in the U.S – he has helped set up the program in several cities across the state of California. “The concept of healthy masculinity has really been a promising approach,” he says. But Lee acknowledges that even if the MOST Club and others like it ran perfectly the strategy of engaging men wouldn’t be a panacea for ending sexual violence against women. “I don’t think it’s the strategy that ends this, because it’s not going to take just one strategy,” Lee says, “but it’s one of the strategies.”

Whether or not future data show that the MOST Club is effective at curbing sexual violence, it’s clear to facilitators like Hall that the club has had a positive impact on the students who’ve come through it. “You start to see that the members of the Most Club start to become active upstanding individuals.” Hall says. “They feel empowered to speak up about things around them that normally they wouldn’t have.”

A glimmer of that future outcome is on display in the classroom here at Brooklyn Collegiate. According to Wehye, the toughest and most recalcitrant student in his class is also the one who has come the farthest. In response to the discussion about whether men should cry, the young man offered up his earnest answer. “I say a man shouldn’t show feelings. But if something is hurting you very bad and you just can’t hold it in, you should just let it go,” he says. “You could get real riled up and do something you would regret.”

1 Comment

I used to be recommended this web site by means of my cousin. I am not positive whether or not this publish is written by means of him as no one else realize such unique about my difficulty. You’re amazing! Thanks!