Can’t wait now for a bigger payoff later?

Study suggests self-control might not be the only thing to blame

Hannah Newman • October 15, 2013

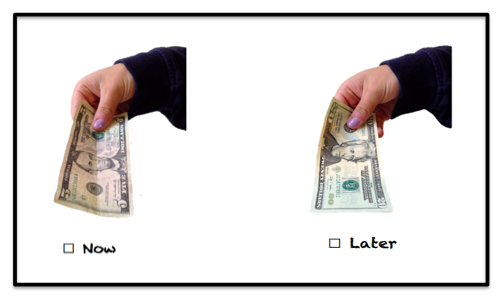

Typical delayed gratification task: a choice between an immediate smaller reward or a larger future reward [Image credit: Rachel Newman]

If I offered you $5 now or $20 in seven days, would you be willing to wait? A new study suggests that delaying gratification – waiting for the twenty bucks – is a product of not only your self-control but also how much you believe I’m good for the dough.

The findings reveal that social trust is a key factor affecting your willingness to wait for a larger future reward. This means that individuals who are often labeled “impulsive” or “lacking self-control,” such as repeat offenders, overeaters and substance abusers, may simply be acting in accordance with what past experience has taught them – a 2008 study, for instance, found that detrimental early childhood environments are strongly associated with high levels of impulsivity. Why believe in a future reward when it’s never shown up before?

The research, led by Laura Michaelson, a doctoral candidate in cognitive psychology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, was published in June in Frontiers in Psychology. It’s extremely significant, Michaelson said, because “this is the first causal demonstration between perceived trustworthiness and delayed gratification.” The team recruited 172 adults aged 18-64 using Mechanical Turk, a popular online survey tool. Each participant read a story about a fictional character described as trustworthy, neutral, or untrustworthy. On the screen next to the story was an image of a computer-generated face that differed in facial characteristics – such as distance between the eyes and eyebrows – known to affect perceived trustworthiness. After reading the story participants were asked hypothetical questions, which were accompanied by the same face from the vignette. For example: If this character offered you $5 now or $15 in a week, how willing would you be to wait for the $15?

Participants presented with untrustworthy fictional characters were 33 percent less willing to wait a week for a future reward than those who met trustworthy characters. The research provides “strong empirical evidence” that the willingness to wait for a larger reward significantly depends on how trustworthy you perceive the person offering you the deal to be, said Celeste Kidd, professor of brain and cognitive sciences at the University of Rochester, who was not involved with the research.

While some researchers have deemed the study noteworthy, others have said its claims of novelty come up short. “Willingness to choose delayed rewards depends on trust expectations, and their study demonstrates this, but it is not news in the scientific literature,” said Dr. Walter Mischel, professor at Columbia University and creator of the seminal “marshmallow test,” where children choose between eating one marshmallow immediately or sitting and waiting for a second marshmallow.

“Mischel was a pioneer of trust ideas and clearly shaped the entire field of study,” Michaelson said. “However, before our studies, the nature of the relationship between social trust and delaying gratification remained unclear.”

In our society, where we routinely blame biology over circumstance, Michaelson’s finding suggests that this attitude may be only part of the story. Perceived trustworthiness provides “an alternative explanation for why [people with criminal records, overeaters and substance abusers] might struggle that is less stigmatizing than our classic notion of lack of self-control,” Michaelson said.

An individual’s willingness to delay gratification is a nuanced matter, perched between nature and nurture. “The general life lesson to be taken away here is that some human decisions that we consider a failure are actually quite sensible based upon that person’s individual experiential history” Kidd said. With this understanding, we can “know what needs to be changed in a person’s environment to avoid disorders of self-control,” shaping intervention strategies to promote stable environments and reliable support networks, Kidd said.

4 Comments

Great article Hannah!!

Great article and it got me wondering about some of the social – cultural narratives we tend to exercise around gender, say, and race, and so I’m wondering how trust gets played out (good or bad or whatever) through these narratives, compelling someone to pre-conceive (pre-judge) another?

Yay Hannah!

I think this is particularly important when understanding why crime rates are so high for newly arrived refugees. These people have learned to trust nobody, not just individuals or a subset of society. It’s no wonder they are impulsive, restless and disruptive to society. Many have probably never known a stable environment and working/saving for the future would be a foreign concept as it requires them to have the confidence in the future to invest their time and efforts building a life.