Plankton to the people

Researchers reach out to citizen scientists to identify species

Alexandra Ossola • November 14, 2013

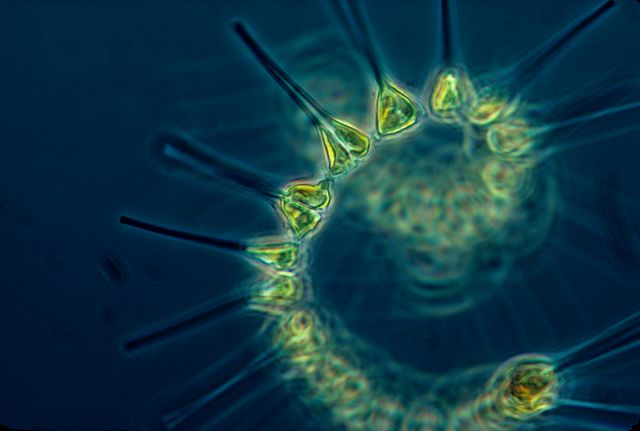

Identifying a few of these little guys could give scientists a bigger picture of the ocean’s complexity. [Image credit: NOAA MESA Project via Wikimedia Commons]

Microscopic and unable to propel themselves, plankton are tossed at the mercy of the ocean. Despite their tiny size, they’re a crucial part of the marine food web, serving as food for everything from jellyfish to whales. They’re also so numerous that they play a significant role in the global carbon cycle, pulling carbon dioxide from sea water and releasing oxygen. Plankton can be almost any type of life – animals, protists, algae, even bacteria – and they are one of the most abundant life forms on the planet. So it’s natural that researchers who want to understand the ocean need to understand plankton.

But the problem is that there are so many plankton species – at least 5,000, most of them microscopic – that identifying individual species is a time-consuming scientific chore. To lighten the load, a team from the University of Miami has asked for help from interested citizens via an online database called the “Plankton Portal.”

The first stop when accessing the new web site is a short tutorial. Visitors look at images of plankton and drag arrows to indicate the length and width of the organisms they see, as well as which direction they’re floating. They then classify the plankton based on their general appearance (jellyfish-like, head with tail, etc.). The more plankton individual participants identify, the more skilled and accurate they become, making their input increasingly valuable to researchers.

The portal has only been open since September, but in its first two weeks the site’s visitors—many of them school kids—classified about 7,000 plankton images, says Jessica Luo, a graduate student in marine biology at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences. For researchers to look through this many images, Luo says, they would have needed seven weeks; that’s five more weeks that the researchers have to figure out what the data really means.

Plankton are crucial indicators of ocean health. Researchers like Robert Cowen, a professor emeritus of marine biology at the University of Miami, use their population numbers and species diversity to tell them how larger fish are doing. These predator-prey relationships are not yet well understood, Cowen says, because they vary drastically depending on which plankton are present. Since the plankton drift with weather fronts and currents, Cowen and his team can get a more accurate picture of the movements of the ocean—and the organisms that inhabit it—by keeping close tabs on types and concentrations of plankton.

The citizen-scientists are reviewing images taken by an innovative camera called the In Situ Ichthyoplankton Imaging System, or ISIIS. Scientists deploy this camera in the plankton’s natural habitat, and use a bright light to capture their movements by tracking their shadows. Imaging has several advantages over traditional sampling methods that use fine mesh nets, which can tear up gelatinous plankton and other fragile organisms, says Louisiana State University oceanographer Mark Benfield, who is not involved in the project. Thus ISIIS and other imaging systems like it give researchers more accurate data, even down to the positions of individual organisms, in many cases.

The Plankton Portal is just one example of an ever-expanding array of citizen science projects tackling all sorts of issues, from figuring out what verbs mean to determining the ecological benefits of specific tree species. But there are still questions about the quality of data analyses done by non-professionals; academic journals so far have been reluctant to publish the results of such projects. Their reluctance stems from “a mistrust of citizen science datasets” because many researchers aren’t vetting their data enough to ensure accuracy, according to a 2012 article on the problem published in the International Journal of Zoology.

But the Florida team doesn’t have any qualms about the accuracy of their plankton data. “We have rigorous data quality control mechanisms in place,” says Luo, which include comparing the team’s classifications to those done by the citizen scientists, and following a “majority rules” tactic if there are classification discrepancies.

Other researchers say the idea is worth trying. “I could definitely see a use for this,” Benfield says. “I’d like to learn more about how effective it is, but it certainly sounds like a good idea.”

1 Comment

Australian researchers have recently discovered a potential blue green algae cyanobacterial cause of Motor Neuron Disease (MND) & Lou Gehrig’s ALS and other Neurodegenerative Diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinsons & a possible L-Serine Treatment for these illnesses see http://www.science20.com/australian_researchers_discover_potential_blue_green_algae_cause_treatment_motor_neuron_disease_mnd_als-121193

It would also be good to identify all of the strains of cyanobacteria and blue green algae that are releasing toxic BMAA into the water and our environment and bioaccumulating in our food.Large blue green algae blooms can be found in the Antarctica, on our beaches, in our lakes and rivers and in our drinking water supply.