Fusing the Manhattan Project into a national park

A newly authorized park hopes to make the forgotten history of the atomic bomb public knowledge

Jennifer Hackett • January 2, 2015

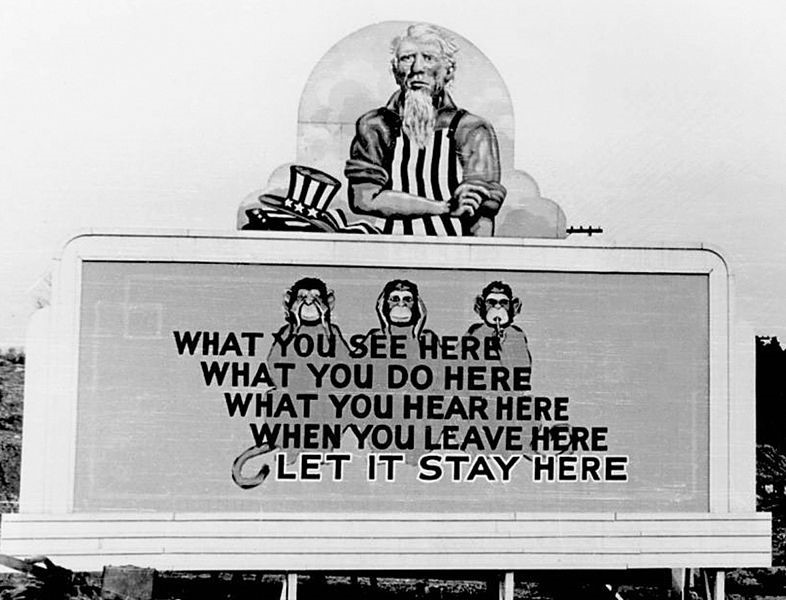

Although a sign outside Oak Ridge National Lab warned visitors to keep its research quiet, a new national park wants to share the secretive history of the Manhattan Project. [Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons]

Los Alamos, Oak Ridge and Hanford were the names of the best-kept secrets of World War II — and they may soon be the sites of the newest national park. They make up the major locations of the Manhattan Project, the nation-spanning scientific mission to develop a nuclear weapon before Nazi Germany that lasted from 1942 to 1946. It was a true success story with a dramatic conclusion: The atomic bombs developed across the three sites were used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan to devastating effect. While today all three locations still boast active research labs, their wartime role is mostly forgotten.

The Atomic Heritage Foundation, the National Parks Service and the U.S. Department of Energy hope to change that. The foundation, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C., has worked to preserve and promote the memory of the Manhattan Project since 2002. Establishing key Manhattan Project locations as a multi-site national park has been one of its major goals. Twelve years later, it’s one within reach: On Dec. 19th, 2014, President Obama signed the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act. Included within this act is the authorization to establish a new Manhattan Project National Park.

“It’s been a long journey,” said Robert S. Norris, senior fellow for nuclear policy at the Federation of American Scientists and a board member of the AHF.

The proposed national park would create a way to tell the story of the Manhattan Project across the three key places involved in the atomic bomb’s creation: Los Alamos, New Mexico; Oak Ridge, Tennessee; and Hanford, Washington. “They showed that you could use uranium to get plutonium at Oak Ridge, that they could do it on a large scale at Hanford, and then they put it all together at Los Alamos,” said David Keim, director of communications at Oak Ridge National Lab.

While all three have historical exhibits, they’re site-specific. “The Park Service would basically pull the full story of the Manhattan Project together,” said Heather McClenahan, executive director of the Los Alamos Historical Society. “There is no place that does that.”

The National Park Service would establish visitor centers at each site, providing a hub of information about the Manhattan Project on a national scale. Each site would then have specific exhibitions highlighting their unique history within the larger historical context.

This isn’t the first time the park proposal has been up for a vote. It was defeated in the House in 2012, largely due to opposition from former Democratic Representative Dennis Kucinich of Ohio. He argued “the effects of the bomb were nothing to celebrate or glorify.” The history of the Manhattan Project is rife with controversy, and there is still no clear consensus on whether the decision to use the atomic bomb on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, causing almost 200,000 civilian casualties, was morally justified.

According to McClenahan, Kucinich’s concerns are unfounded. “Government agencies trust the National Park Service to do a fair job covering history,” she said, citing Manzanar National Historic Site, which memorializes Japanese internment camps, as an example. “Those things aren’t glorified. They’re looking at history, not burying our heads in the sand.”

Exhibits at Los Alamos National Laboratory already discuss the ambiguous morality of the decision to use the bomb and how to move forward in the post-atomic world, McClenahan continued. The park would expand on these exhibits rather than try to whitewash them. “There’s a huge story about what happened when the bombs were dropped on Japan, and the debate that went on over the control of nuclear weapons after. [That story goes] beyond our scope, and we’re anxious to get the Park Service to help us tell it.”

No matter how contentious its legacy, the Manhattan Project signaled a major turning point in scientific research. “Prior to World War II, the drivers of science were German,” said Lee Riedinger, a professor of physics affiliated with Oak Ridge National Lab. “All of that changed after World War II.”

The postwar period saw the rise of large national laboratories funded by the government. According to Keim, the Department of Energy became the largest funder of physical science in the United States directly because of the Manhattan Project. It set the trend for future research by showing just how successful well-financed, large-scale research efforts could be, especially when they brought scientists from around the world together to collaborate on them.

The Manhattan Project also brought about the nuclear age and all its associated controversies. Nuclear power continues to be an environmental issue, as both a source of clean energy and a major contamination threat, while the nuances of nuclear proliferation continue to play an active role in international relations. Both Los Alamos and Oak Ridge are still functioning national labs that continue to play a role in these nuclear issues: The Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge is chiefly responsible for maintaining and ultimately disassembling the national stockpile of nuclear weapons. Hanford, on the other hand, demonstrates the dangers and difficulties of nuclear waste clean-up. Active parts of the labs will be off-limits to visitors, although McClenahan hopes that tours of Los Alamos National Lab will be made available to the public as special events.

The Manhattan Project National Park would be the thread that ties all three sites together, providing a stronger national context and enabling larger topics such as the morality of the bomb, the long-lasting impact of the Manhattan Project on American science research and the nuances of living in the nuclear age to be discussed. Now that it’s been authorized, securing a source of funding is the next step towards this new national park.

1 Comment

This is a story that needs to be told. I hope it happens.