Cassini was a heart-breaker

Social media made us love—and mourn—a space robot

Jessica Boddy • October 23, 2017

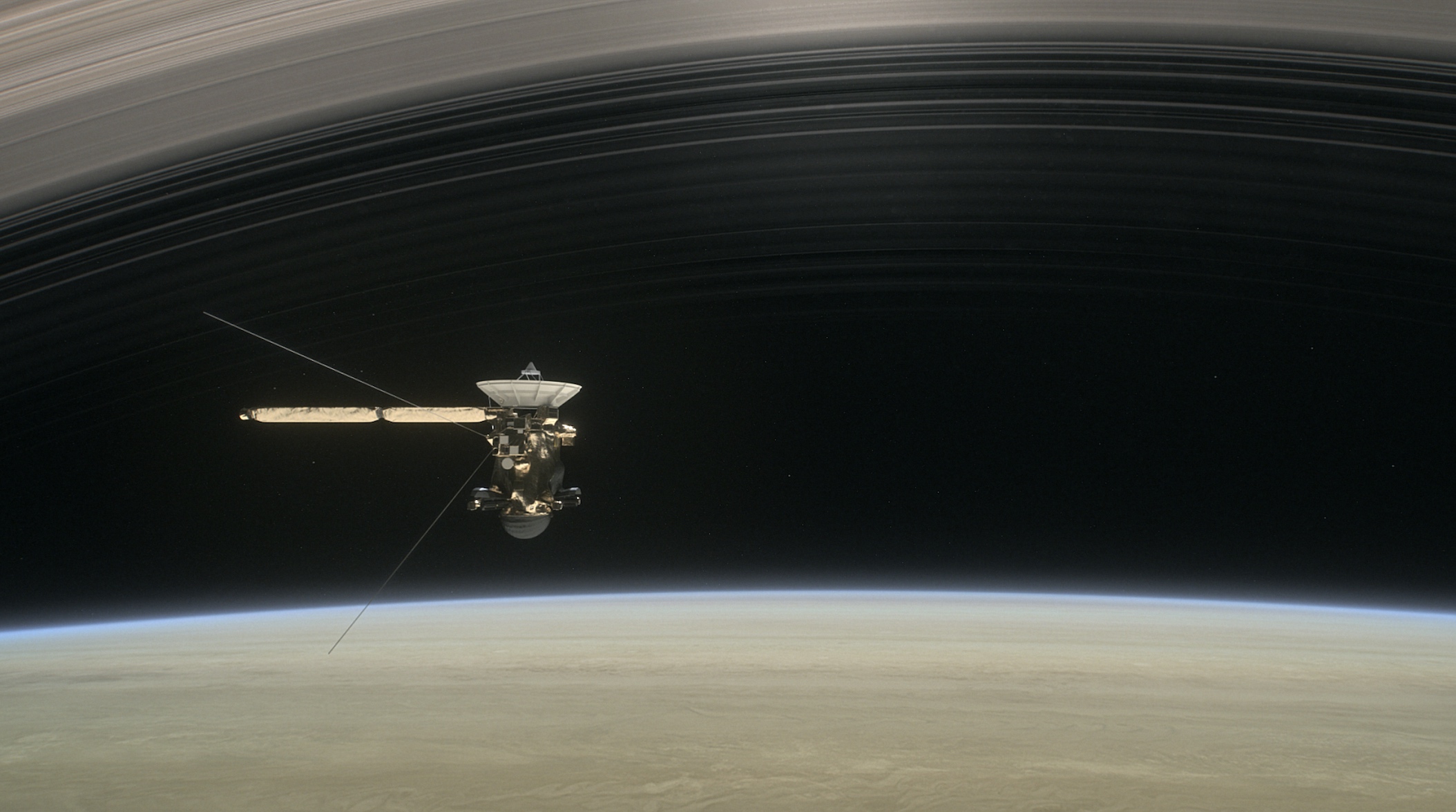

Cassini dove through Saturn's rings and into the planet's atmosphere in its final moments. On Earth, Cassini-lovers mourned. [Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech]

When Cassini plunged into Saturn last month, peoples’ hearts broke. Admirers held funerals. They cried. They flooded Twitter with mournful gifs.

Just got all chocked up inside pic.twitter.com/lIsnyulZy2

— TxRaven (@TxRaven1) September 15, 2017

Apparently this was the last transmission pic.twitter.com/fUUNLvSxLN

— Craig Hamer (@CraggleMcHamer) September 15, 2017

The NASA space probe launched in 1997. In its 20 years in orbit, it taught us a lot about Saturn. It explored the planet’s moons and provided data that will fuel scientists’ work for years. Then on Sept. 15, 2017, Cassini, unable to travel much further on an empty fuel tank, plunged to its demise in an effort to collect more data about Saturn’s atmosphere. Cassini faithfully transmitted those final numbers and images during its last seconds.

While it was really just a hunk of metal, the robot was often given human-like qualities on social media. This made it so devastating when Cassini died—even though it was never alive in the first place. Todd Barber, the lead propulsion engineer for Cassini, was one of those who broke down.

Barber worked on Cassini since the mission’s start. After 20 dedicated years, “I did my final status report counting how much propellant we used to the last second of data,” Barber recounts. “And when I did that I just burst into tears.”

But it made sense that Barber would cry. He had worked closely with Cassini for much of his career. Why had the rest of the public reacted similarly?

“We’ve had numerous prior vehicles up there [in space],” says Douglas Gillan, a cognitive psychologist at North Carolina State University. “This was the first one that I’ve noticed with such a widespread response.”

Responses to other spacecraft going offline have never been quite like this. In 2008, NASA’s Phoenix Mars lander “died” in harsh Martian weather, and the response was lackluster, to say the least. One Twitter user was even relieved it died, tweeting, “RIP Mars Phoenix Lander. Your annoying Twitter updates will be missed by a few, I’m sure.”

Gillan says social media played an essential role in why Cassini, a simple, school bus-sized spacecraft, tugged at the heartstrings of so many.

Back in 2008, Twitter only had 6 million users. Today it has over 300 million. What’s more, NASA has stepped up its social media game. Nearly every post to @CassiniSaturn has a flashy photo or a link, and the account has over 1.5 million followers. (Poor Phoenix only has 294,000.)

“If I can’t really articulate what my feelings are, and then I see other people are grieving on Twitter, maybe I start grieving,” says Gillan. “It’s a social response.”

Gillan adds that the grief around Cassini also stemmed from how we anthropomorphized the robot. People drew comics of Cassini talking to Earth and Saturn, referred to it as a friend and thanked it for its data.

Now, as we continue on after the loss, grief is turning into pride. Many post the spacecraft’s photos of Saturn and its moons with messages of hope and wonder.

“Cassini was a marathon — a long, beautiful mission with a continuous flood of data,” Barber says. He feels validated by the public’s reaction to Cassini’s final moments. “We never knew if people were paying attention.”

Now he knows they were.

He believes it was Cassini’s data and benefit to science that endeared the spacecraft to the public. “Maybe that’s why they were invested in the mission and felt sadness with us,” he adds.

In the end, “I’d think Cassini would say, ‘don’t weep for me. I lived a long happy life, I went out on my own terms, I did science to the very last second,’” says Barber. “That’s how I’d want to go.”