Chemistry Nobel honors discoverer of unique solid matter

Sole chemistry winner recognized for controversial work on quasicrystals

Miriam Kramer • October 5, 2011

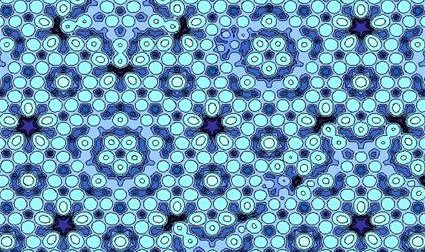

Quasicrystals, like the one above, are not composed of a random assortment of atoms or have a repeating structure, putting them in their own class of solids

After nearly being kicked out of his research group for defending his controversial findings, it looks like Israeli scientist Daniel Shechtman will have the last laugh.

Today, Shechtman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery that isolated him from his colleagues back in 1982. By putting a quickly cooled glob of metal under an electron microscope, he was able to observe an extremely unexpected way for matter to arrange in a solid form now known as quasicrystals.

Before this finding — and for some time after as the scientific community rebelled against Shechtman — it was thought that solid matter could only be arranged in a constantly repeating and rigid atomic arrangement (like diamonds) or a totally random assortment of atoms (like glass). Quasicrystals, however, do not fit into either of those categories perfectly.

Instead, on an atomic level these solids take the form of ancient mosaics found in Iran and Spain. Both quasicrystals and these mosaics do not repeat their pattern, but still follow an overarching and accepted order, a formation thought impossible before this discovery.

In the years since Shechtman’s findings became scientifically accepted, many quasicrystals have been fabricated in a lab setting, but only one — an alloy of aluminum, copper and iron in Russia — has been found occurring naturally.

Quasicrystals could aid in the development of new materials for products like non-stick frying pans, engines, and LED lights. But those inventions are probably a long way down the road. For now, Shechtman can rub his detractor’s faces in his $1.5 million prize and the definition that he changed in the International Union of Crystallography.