Mineral Monday: Olivine

Mineral names, elements switching places, and olivine!

Mary Beth Griggs • October 17, 2011

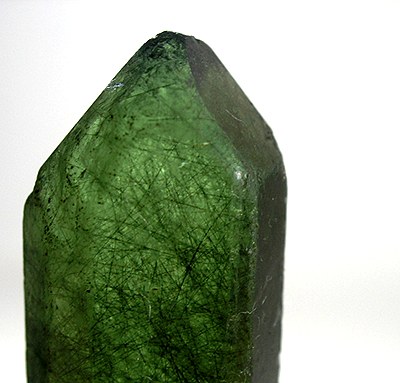

Olivine Crystal (Image Credit: Rob Lavinsky)

I have a wonderful friend who is a graduate student in chemistry. While we were both undergrads, she happened to take a course in geology*, and she told me that the mineral names geologists used drove her nuts. They didn’t make sense — why not just say silicon dioxide instead of quartz?**

The simple answer is that geologists just take a certain perverse pleasure in confusing everyone else in the scientific world.

I’m kidding. Geologists just like naming things.

There’s a certain evocative quality to names — cinnabar sounds much cooler than mercury (II) sulfide. But beyond that, there are some practical reasons for naming gems and minerals in geology, and most of them have to do with the simple fact that the chemical formulas for minerals are weird — and they often don’t help in the field, where geologists need to be able to classify the rocks they’re looking at without a lot of extraneous equipment. There’s plenty of time to do that when they get back to the lab (and it’s way more fun to bring back rocks from the field than to haul a microscope into the wild).

Which brings us to olivine, the mineral of the week. Olivine’s chemical formula is (Mg, Fe)2SiO4, which, as stated before looks a little weird. It is a mineral series — olivine is a magnesium iron silicate. While it will always have the silicate part (SiO4), magnesium and iron trade places in the elemental front seat. If there is only iron in that spot, it gets the name fayalite, and if magnesium hogs that area, then it’s called forsterite.

Most olivine samples fall somewhere between the two: a mix of iron and magnesium. This is because olivine is a solid solution — and magnesium and iron are similar enough that they can sub in for each other as olivine crystallizes from magma, which is essentially one giant, super-heated mess of elements and minerals hanging out and interacting with each other, just like they do in chemistry. We’ll talk even more about this stuff next week when I introduce you to the greatness that is phase diagrams.

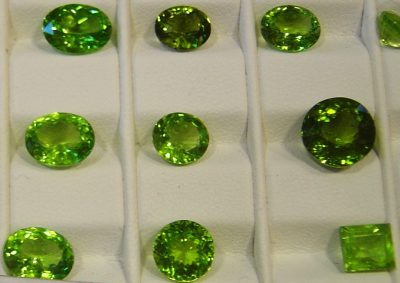

For now, a little bit more about olivine. Olivine has a gorgeous green color, and while the crystals are usually hidden within the fabric of igneous rocks, sometimes its crystals can grow large enough to be gem quality. When this happens we give it yet another name, because it sounds cool: peridot.

* I also took a chemistry course while an undergrad — she did much better at geology than I did at chemistry.

**I don’t actually remember what mineral it was that we were talking about. Quartz is just my go-to.

3 Comments

What’s the difference between the transparent gem, peridot, my birthstone, and the rock, olivine? Now I want to learn about rocks on a Friday night. Go Scienceline!

Hi Ashley!

Great question. Peridot, the gemstone, is the crystal version of olivine, which just means that it’s molecular structure is nicely arranged. It had time to grow, repeating the same chemical formula in three dimensions, until it was visible to the naked eye (which is awesome!) Olivine and Peridot have the same chemical formula: (Mg, Fe)2SiO4, but olivine very rarely has the chance to grow into large crystals-that takes both time and space, which are both hard to come by in a magma chamber. Usually that nice chemical formula gets all mixed up with other minerals that are forming from magma at the time, so olivine gets distributed throughout a rock, lending it a green tinge if you’re lucky, but no pretty crystal shapes. Hope that helps!

MB

This was great info Mary Beth!(if i may)

Finally, i can see the connect between Olivine and Peridot.

thanks to Your explanation.

The simplified chemical explanation finished it for me.

excellent