A rogue conservationist fights for the return of Britain’s busiest mammal

In his new book, Derek Gow tells the story of his intrepid rewilding campaign

Abe Musselman • December 4, 2020

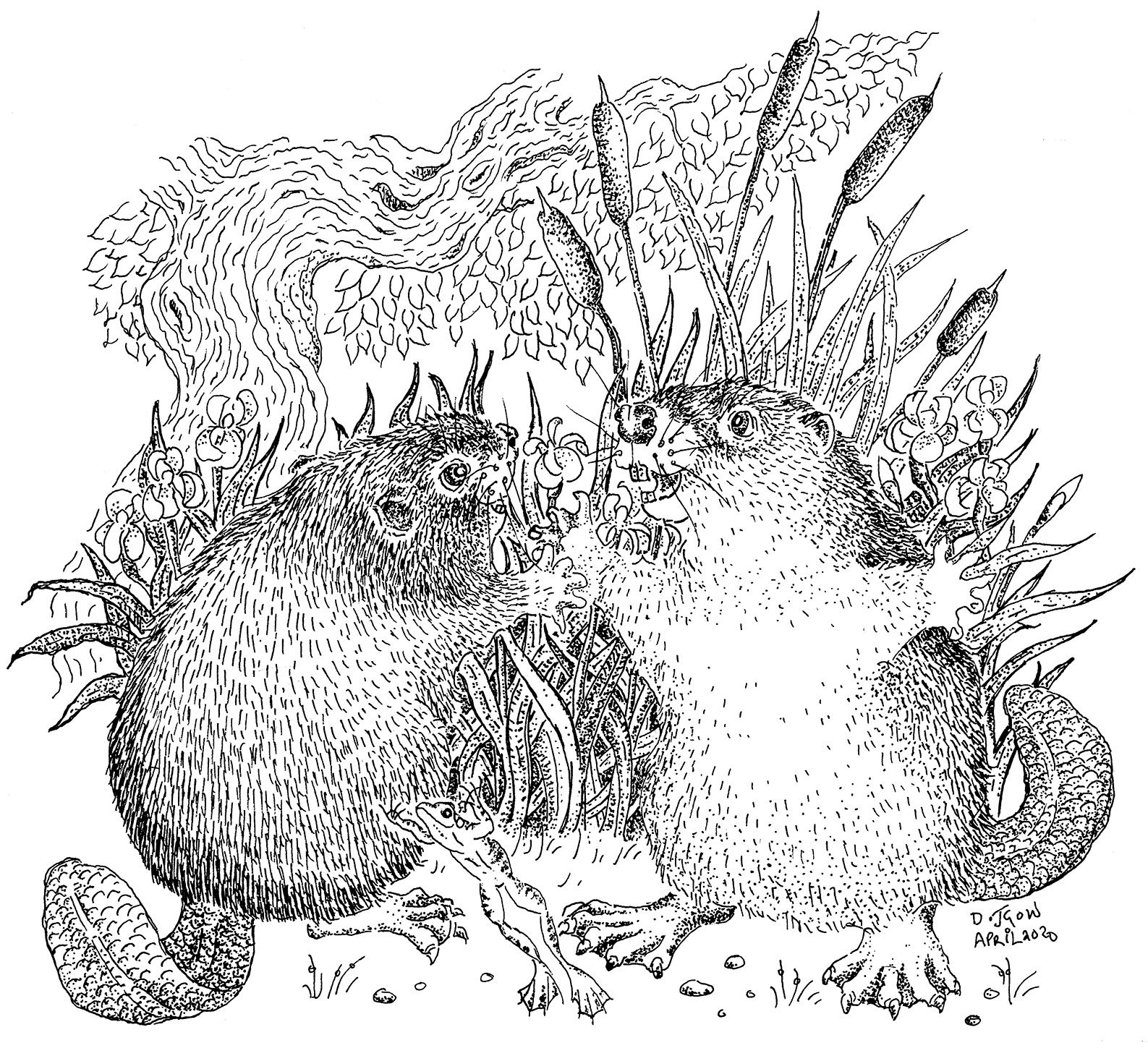

Author Derek Gow has spent more than 20 years working to reintroduce beavers to the British landscape. [Credit: Derek Gow, Chelsea Green Publishing | Used with permission]

Alfred Russell Wallace, a friend of Charles Darwin, was born too late to see the giants of the ice age firsthand. “We live in a zoologically impoverished world,” he wrote, “from which all the hugest, and fiercest, and strangest forms have recently disappeared.” I’ve always read his words as a lament, but also a reminder of how much more we have to lose.

Beavers are the second “hugest” living rodent, and they’re fierce and strange too. But conservationist Derek Gow has had a hard time rallying people to his cause: reintroducing beavers into Great Britain, where they’ve been extinct for 400 years. His line of work is known as rewilding, a bold conservation strategy that aims to let nature do as much work as possible.

In Bringing Back the Beaver, published by Chelsea Green Publishing, Gow recounts how he and a handful of beaver fanatics tried, failed and tried again to get the British people to see the beaver not only as charismatic, but essential and maybe even majestic. His campaign illustrates the challenges of conservation in the developed world and the reasons why so many of us are willing to fight to restore what previous generations have destroyed.

From the very beginning, our species has modified the world around us, shaping it to suit our purposes. As we’ve outgrown our wild origins, out of an instinct for self-preservation, we’ve pushed the wilderness and its inhabitants to the margins. In their place, we’ve created civilization, a new natural order built by human hands.

Now, in this late stage of the human story, some have started to wonder whether we’re fit to rule after all. We’ve grown nostalgic for the mystery of the untamed world, where we took our first uncertain steps alongside huge, fierce and strange forms.

But if we know where to look, we can find the wilderness knocking at the borders of civilization, eager for a chance to return. All it needs is a little help.

Cult of the beaver

Humans have been fascinated with beavers for millennia, says Gow. He’s the latest in a venerable order of beaver keepers.

Beavers appear in mythic traditions as far apart as those of the Celts and the Blackfoot tribe of North America. Medieval pharmacists used castoreum — a yellowish ooze drawn from sacs near the beaver’s anal glands — to treat headaches and fever.

But over time, our attitude toward beavers shifted from reverence and curiosity to greed. The fur trade wiped out beavers in Great Britain, and European colonists nearly did the same in North America as beavers transformed from creature to product. In one harrowing passage, Gow describes how trappers would kill as many beavers as they could within an area to make sure their competitors didn’t move in on the territory. “The pain. The misery. The fear. The destruction and death this caused bothered them not at all,” he writes.

These days, beaver enthusiasts are a proud few. You can spot one, says Gow, by “the kind of tedious zeal generally restricted to deluded members of obscure religious cults.” Over the course of the book, he introduces the reader to some of the cult’s most colorful devotees, from conservation-friendly members of the landed gentry to an eccentric scientist “who would not have been out of place on a Shackleton expedition killing a narwhal with an axe in order to measure the length of its penis.”

Gow’s own moment of conversion comes during a visit to a remote beaver farm in Poland. The keeper reaches into a concrete beaver lodge and pulls out a drowsy mother, handing her to Gow. She settles into his arms and fills the room with “wood and herbs…the indescribable sweet smell of beavers.”

“I have seldom known such rapture,” he says. To each his own.

Rage against the machine

Gow’s many opponents range from farmers and sport fishermen to obtuse politicians and bureaucrats. In describing one British environmental department, he remarks that “most of its employees are drawn from the university of prevarication. Once employed,” he says, “their principal goal is to outcompete their fellows in ensuring pointless delay.” In certain entertaining passages, Gow channels Wendell Berry, adding in a healthy dose of Scottish rage.

But his greatest enemy is inertia. In the space of 400 years, the British have forgotten what it’s like to live alongside the beaver, and people are slow to change. Beavers are ecosystem engineers: species that make changes to the physical landscape. While traces survive in the form of old dams and lodges — and the shapes of rivers as they bend around them — the work of the beavers has been mostly erased by human settlements. We’ve replaced their handiwork with our own. In a world of skyscrapers and bridges, beavers can’t compete.

In his fight to tip the balance, Gow takes advantage of serendipity and every loophole he can find. He recounts his exploits with the unhurried voice of a practiced storyteller. When a real-estate developer goes looking for a PR-friendly way to make use of leftover land, someone points him to Gow. Their plan to release two breeding-pairs of beavers is nearly thwarted by the government, but at the last minute, the owner announces he will name the beavers after members of Parliament, bringing a swarm of media attention that tips the balance in their favor.

Others resort to tactical re-beavering. Gow describes how a renegade Belgian conservationist, frustrated with the farming lobby’s obstruction, coordinated the release of a hundred beavers into Bavaria under the cover of darkness. Once the beavers are set loose, there’s little the government can do about it.

Return of the wild

Rewilding represents a relatively new and unconventional philosophy in the conservation world. While traditional conservation tries to preserve an ecosystem by drawing boundaries and managing the land, rewilders often let nature build a new ecosystem from the ground up. They populate the land with a few key species, then they step away and let the wild get to work.

It’s not as far-fetched as it sounds. As Gow notes, wild boars have done just fine without any help from people like him. Driven extinct in Britain in the 1600s, domestic boars eventually reestablished a wild population about 30 years ago. “They just escaped from poorly fenced farms, met others that had done the same and bred.” Maybe rewilding works best when it happens by accident, with as little human touch as possible.

Gow has seen firsthand the horrors humans can bring about when they’re in control. In one of the book’s most memorable scenes, he takes a tour of a dodgy wildlife park in post-Soviet Poland. On his way to the beavers, he encounters a host of “random biological experiments,” an uncanny menagerie that includes a hybrid bison-cow and a herd of “tame” deer with murder in their eyes, a vision of the wild seething beneath the bonds of human repression.

Rewilders learn to grow comfortable with chaos, the kind of surprises that inevitably occur when humans interact with the wild. Upon receiving his first shipment of beavers, Gow is attacked by an irate female and has to fight her off with a broomstick. Later on, he suffers a nasty infection when a beaver bites him in the breast. In his accounts of these incidents, Gow doesn’t seem afraid. He’s thrilled at the way the wild reasserts itself, even in captivity.

Time and again in Gow’s story, beavers escape their human captors, slipping through nets and chewing through the walls of their pens. Months after they’ve disappeared, signs of their work begin to appear in the landscape. “Suspicious piles of woodchips…teeth marks…well-worn foraging paths.” Dams go up, and after long enough, the land itself begins to change. Wetland shrubs grow along the new-formed pond. The banks fill up with insects and small mammals, the water with fish. The wild returns.

Watching beavers at work, it’s hard not to ascribe them human traits. They’re industrious, determined to get the job done. But their minds and motives are completely alien to human experience, something we can never truly understand. This sense of strangeness is one thing we’ve lost as we’ve remade the world in our image.

Ultimately, what distinguishes rewilding from other conservation strategies is humility, a willingness to share the Earth with intelligences that aren’t our own. Beavers were shaping the planet long before humans decided we should be in charge. They remind us we can’t do it alone.

Gow has won many small victories for the beaver, but his greatest achievement has been capturing the public’s imagination. Without enough public support, conservation efforts can’t succeed in the long term. His campaign has reminded the British people what they’ve lost and what they could have again if they’re willing to make space.

As I finished out the book, I imagined a lone traveler, a hundred years from now, encountering a feral beaver in the wildlands of Great Britain. Could it be different next time?