Dancing in digital immortality

The evolution of Merce Cunningham's "Loops"

Ashley Taylor • July 16, 2012

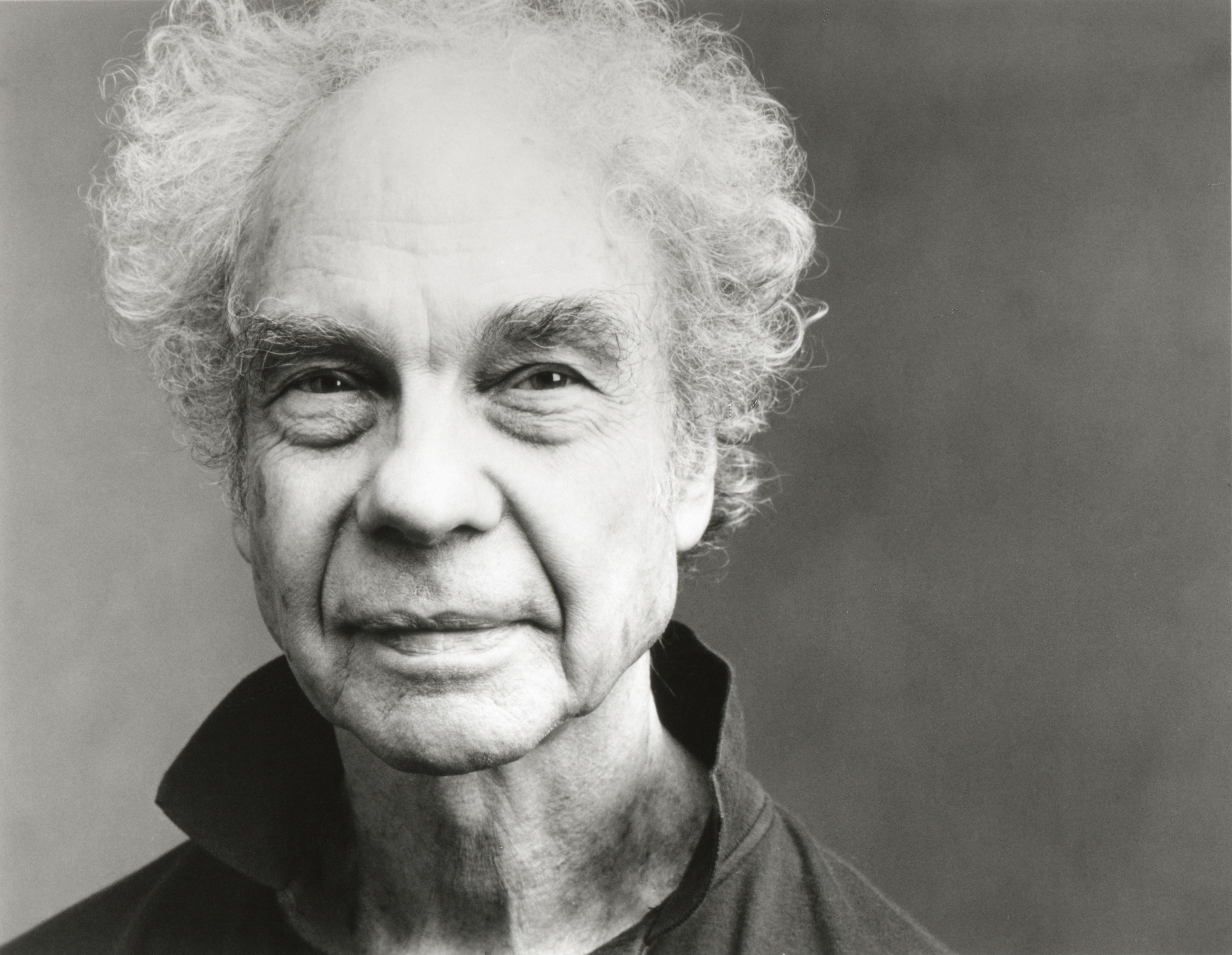

The late choreographer Merce Cunningham (1919-2009) lives on in more ways than one. [Image credit and copyright: Annie Leibovitz, courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust]

The modern dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham died in 2009, and his company gave its final performance at the end of last year. Many of his dances will live on in the memories of former company members who go on to restage them. But there’s one solo, “Loops,” that Cunningham never taught to another dancer. This piece lives on through a different medium: digital motion capture.

“Loops,” which Cunningham choreographed for himself in 1971, explores rotations of all kinds. Originally a full-body dance, “Loops” eventually narrowed to Cunningham’s hands alone. In old age, Cunningham performed the piece seated in a chair. Now no live performer knows “Loops.” But computer programs do, and they continue to create variations of Cunningham’s work. Do these digital variations memorialize or haunt the choreographer?

In August of 2000, OpenEndedGroup, a trio of digital artists in New York City, affixed reflective markers to Cunningham’s hands and had him perform “Loops” in front of infrared cameras, which recorded the markers’ positions over time as a set of data points. This technique for digitalizing movement is called motion capture. You may have encountered it in digitally animated films such as The Adventures of Tintin and in certain interactive videogames — Kinect for Xbox 360 is an infrared camera that tracks the skeleton. In the dance world, motion capture is known as the technology behind BIPED, a 1999 collaboration between Cunningham and OpenEndedGroup, in which live dancers interacted with digital forms created using motion capture and projected on a transparent scrim. This time, motion capture recorded Cunningham himself.

OpenEndedGroup wrote software to interpret the data from Cunningham’s performance. The result is quite different from the original. As the Kaiser described it, “we’d have a cat’s cradle as well as hands, we’d have all these relationships that were going beyond human anatomy.” The program made on-the-spot decisions about how to connect the motion capture dots. Altogether, OpenEndedGroup created four versions of “Loops” — tweaking the software every time. Of those, the first three were “all computed in real time, so they were basically improvising the same way [Cunningham] had.” Kaiser refers to the way Cunningham varied “Loops” — and most of his works — from performance to performance using “chance operations,” such as rolling a dice, to determine the sequence of motions. In contrast, the last performance of OpenEndedGroup’s “Loops,” at Lincoln Center last spring, was a 3-D film, not a live run of the software, and Kaiser called it the “definitive version” of the piece.

The above video is silent.

The future of “Loops” would prove to be anything but definite. OpenEndedGroup made the motion capture data open source. Any artist could download and reinterpret it. At the Boston Cyberarts Festival in 2009, four digital artists did just that — writing software to reinterpret the raw motion capture data. The resulting works were displayed on computer screens at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Museum in Cambridge in an exhibit called “Loops: New Iterations.” The exhibit took place a few weeks before Cunningham died. “The piece became more poignant after his death,” festival artist Golan Levin commented, “because suddenly it was like giving him a body that he had lost, in a way.” Levin, a digital artist from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, used the motion capture data to animate a white a blob-ular structure that looks like a little man kicking and wiggling to get out of a white sac.

And so Cunningham’s work continues to evolve through the technology he championed. Anyone could reinterpret the work today.

If OpenEndedGroup’s Kaiser had his way, no one would do so. “After our experience with Cyberarts, we have no interest in anyone else interpreting it, since it was so stupid,” he said. “None of [the four artists] engaged anything of interest, certainly not with the motions of Cunningham,” Kaiser said. “There’s nothing to deal with the motions. And I just found the whole thing just tremendously simple-minded in the usual way of digital art. Gimmicky. And just not thought through.”

In his iteration for the Cyberarts Festival, Brian Knep, the artist in residence at Harvard Medical School, chose not to engage with the motions of Cunningham. “When I first downloaded and started playing with the captured data,” Knep said, “I kept coming back to the reference footage, captivated by watching Merce’s facial expressions. This had far more meaning to me than any of the data.” For his interpretation, Knep used image reconstruction algorithms to recover detail from the original video footage of Cunningham’s performance, then zoomed in on Cunningham’s face, completely cutting out the hands. Two numbers at the bottom of the screen, the speeds of Cunningham’s hidden hands, are the only representation of the motion capture data.

Here’s how the other digital artists reinterpreted “Loops:” Boston-based Sosolimited used the motion capture data from Cunningham’s fingertips alone to animate text from reviews of Cunningham’s work; Casey Reas, a Los Angeles media artist best known for co-creating the programming language Processing, created software that used the motion capture data to animate two curved forms, one black, one white, connected by threads.

The above video is silent.

No one will ever know what Cunningham thought of his new avatars, but Kaiser took offense in his name: “I found the whole thing insulting, if not to us, certainly to Merce.”

Abby Diaz, a graduate student studying digital media at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, is not surprised by Kaiser’s disappointment. “Reinterpreting any masterwork — anything created by Merce Cunningham or Balanchine or any really pivotal choreographer — is incredibly difficult because you’re trying to up the ante against a work that’s super progressive, something totally different.” She thinks that both funding and talent will limit people who try. “I think it’s a little naïve to think that when you open source code, people are going to make masterpieces out of it.”

Though people may disagree about the form they take, Merce Cunningham’s motions will endure as long as there is a computer and an Internet connection. “Loops” has transcended the medium of the dancer. It has a life of its own.

1 Comment

About the most unrewarding few minutes I have ever spent on the Internet. Reportedly, this man was a great artist. These efforts to interpret his artistry seem feeble, disrespectful and wrong-headed.