Geomorphology and the Mississippi

Or, how weather can relate to geology

Mary Beth Griggs • May 18, 2011

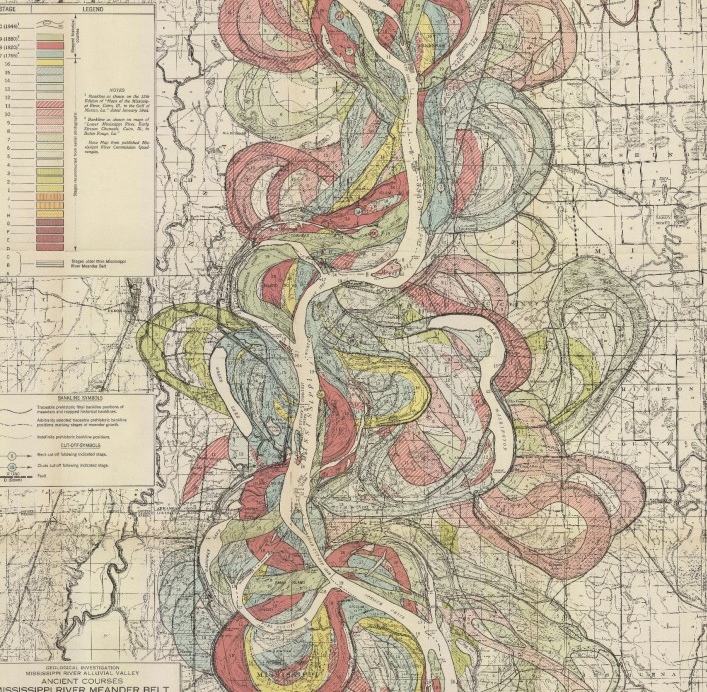

This gorgeous map was drawn by Harold Fisk in 1944. It, and the other beautiful images are available for download at the Lower Mississippi Valley Engineering Geology Mapping Program Image Credit: Fisk, Harold "Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River," Plate 22-9. United States Army Corps of Engineers*

The south has not had it easy lately. Wave upon wave of foul weather has crashed down upon the region- and we haven’t even made it into hurricane season yet**. Tornadoes tore across the southeast last week, devastating huge swaths of Alabama, and repeated storm systems swelled the tributaries of the Mississippi to bursting. But what does this wicked weather have to do with geology?

Quite a lot actually. Volcanoes and plate tectonics are certainly not the only forces that shape the landscapes of this world. Wind, rain, ice, and temperature all play a role too, as the Earth’s surface is constantly changed by the climate. There is an entire branch of geology called geomorphology that examines the interactions of all these forces (including tectonic forces) with the earth’s crust. Literally, geomorphology means the study of the form of the earth. And the form of the earth is constantly in flux.

The rolling peaks of the Appalachian Mountains were shaped by gradual erosion over millions of years. Image credit: MB Griggs

Tornadoes leave little imprint on the geologic record, but other weather and climate driven mechanisms definitely leave their mark on the landscape. Glaciers in retreat scrape across bedrock, scooping out lakes, and laying out islands and hills. Wind and water cut through the high peaks of uplifted mountains, smoothing them over millennia into soft rolling peaks. And rivers… ah rivers. They do fantastically gorgeous things to landscapes, if given enough time. Out west, rivers have cut through layers of uplifted rock, giving us spectacular canyons. No one looking at the Grand Canyon could deny the control that flowing water exerts on the landscape.

The Mississippi does a similar thing. Because the Mississippi and it’s tributaries are all almost at sea level, it isn’t cut down into the landscape like the rivers out west (which are, in a way, desperately clawing their way down to sea level through the underlying rocks (yay gravity!)), but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t constantly changing. The Mississippi is a meandering river, one of the most common river forms on the planet. It snakes across the landscape in big distinctive curves, across a wide flat area known as the floodplain. This is where the current weather becomes a problem.

As you can see in the Fisk map above, the Mississippi has changed course many many times during its history. Each of the different colors was a different course of the river at some point in time. He figured out the ancient patterns through careful geological sleuthing. A river can cut away at the earth’s surface, but it can also leave things behind. The vast floodplain on either side of the river is marked with fine, nutrient rich soil deposited by seasonal floods*** The channel however, leaves behind rockier sediment, allowing someone taking core samples along a river system to see exactly where the river was at any given point in time. The difference in sediment between the floodplain and the channel bed can be explained by the awesomely-named Hjulstrom curve, which shows the velocity water needs to travel for a grain of sediment of any size to be eroded, transported and deposited.

Fisk’s findings, of a Mississippi that liked to change its course, were very worrying for the people living along the Mississippi. People building homes and cities don’t like the idea of the land beneath their feet suddenly not being the land beneath their feet anymore. So the United States built levees along the river. These hulking masses of earth lurked along the river, especially prominent in the areas where the Mississippi was threatening to move from the Mississippi basin to the Atchafalaya river basin. The move, though natural, would have diverted water away from New Orleans, a disaster for the shipping port. And so the levees were put in place, protecting the cities along the river, and enabling cropland to move ever closer to the riverbanks-until now.

Now, in order to save the cities and towns along the Mississippi from disaster, the Army Corps of Engineers has decided to open levees and spillways and locks, allowing the river to flow for a short time in the direction that it wants to, inundating cropland and small communities in the process. This relieves the pressure on the levees further downstream, and lessesns the chance of a devestating flood on larger communities. I don’t envy the man that had to make that decision. As the river’s crest (the high point of the flood) makes its slow way southward from Vicksburg, Tennessee today, it’s worth remembering that the form of the earth is constantly changing, and there’s very little we puny humans can do about it.

*To see the maps put together, visit Pruned, here

**Opening day was May 15 for the Pacific, June 1 for the Atlantic- Visit NOAA’s Hurricane center here

***This is why farmers love planting crops on floodplain. The soil is absolutely great for plants.

1 Comment

This .. is So cool.