Mineral Monday: Kyanite

So what do minerals teach us anyway?

Mary Beth Griggs • October 24, 2011

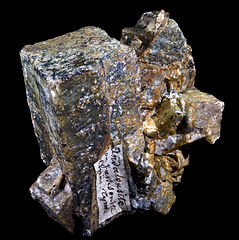

Kyanite [Image Credit: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com]

It’s Monday again! And that means it’s time to rock*.

Last week we talked briefly about olivine, and you learned that geologists love naming things, and also that olivine’s chemical structure can substitute magnesium for iron and vice-versa, giving us one big olivine-y spectrum of compositions.

This week we’re going to add on to that. Many of you might have been wondering why that spectrum matters—who cares** whether olivine has more magnesium than iron? Well, olivine forms in molten rock***, so the composition of the mineral tells us what kinds of elements are found within the magma, giving us a better picture of what lies beneath our feet.

It also tells us what kinds of temperature the olivine formed at. Magnesium-rich olivine melts at 1900 degrees Celsius, and iron-rich olivine melts at a balmy 1200 degrees Celsius. Because olivines with high magnesium content can withstand higher temperatures, they can crystalize out of a cooling magma before the ones with high iron content. Which is just cool.

Whew, that’s a lot of geology. But stick with me folks. We’re getting to the good stuff, and I promise you pretty pictures if you keep going with me.

The point is, minerals can tell us a lot about how the earth works, even when we can’t observe the processes happening directly. Which brings us to today’s mineral: kyanite.

Kyanite (Al2SiO5) is usually dark blue, and it forms spindly thin crystals as it grows. What is fascinating about it is that, like olivine, kyanite can tell us a lot about how rocks formed.

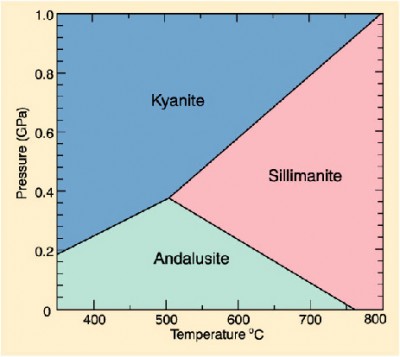

Kyanite has two sibilings: sillimanite and andalusite. Like identical triplets, they all have the same chemical formula: Al2SiO5, and they all form in metamorphic rocks. But they look different, because they were formed under slightly different conditions. Kyanite forms under high pressures and low temperatures, sillimanite likes it hot, and can handle pressure fairly well, but not as well as kyanite, and andalusite is the mild-mannered youngest child who prefers low temperatures and pressures.

Kyanite and its sisters are hardly rare — they are commonly found metamorphic rocks all over the world, making them a useful diagnostic tool. Because they form in such different environments, it’s rare that all three are ever in the same rock at the same time (if they are, that tells you that the rock formed under very specific conditions). Finding kyanite in a metamorphic rock tells a geologist that the rock was formed at high pressure, but that the rock only really encountered temperatures up to 800 degrees Celsius. Their favored temperatures and pressures can be visualized in a phase diagram like this one:

Phase diagrams are great ways of visualizing how minerals form within the earth, but in a way minerals like kyanite are themselves visualizations of information: their presence gives researchers a glimpse into the depths that we wouldn’t ordinarily see.

Of course, they’re also just gorgeous:

*Thanks Sarah!

**Answer: Geologists. They are the only ones that care. But now you do too!

***Usually magma, under the earth’s surface, as opposed to lavas above the earth’s surface. Like any over-achiever, olivine enjoys high-pressure environments.

**** Quick Review for those struggling to remember what the heck metamorphosis is. There are three ways rocks can form: Igneous rocks get cooled down from a melt like magma or lava. Sedimentary rocks are bits of other rocks that have gotten stuck together, metamorphic rocks have been squished and heated, but they haven’t melted yet. Look at the Rock Cycle if you want a visual representation.

Next Week for Halloween: Spell ingredients!