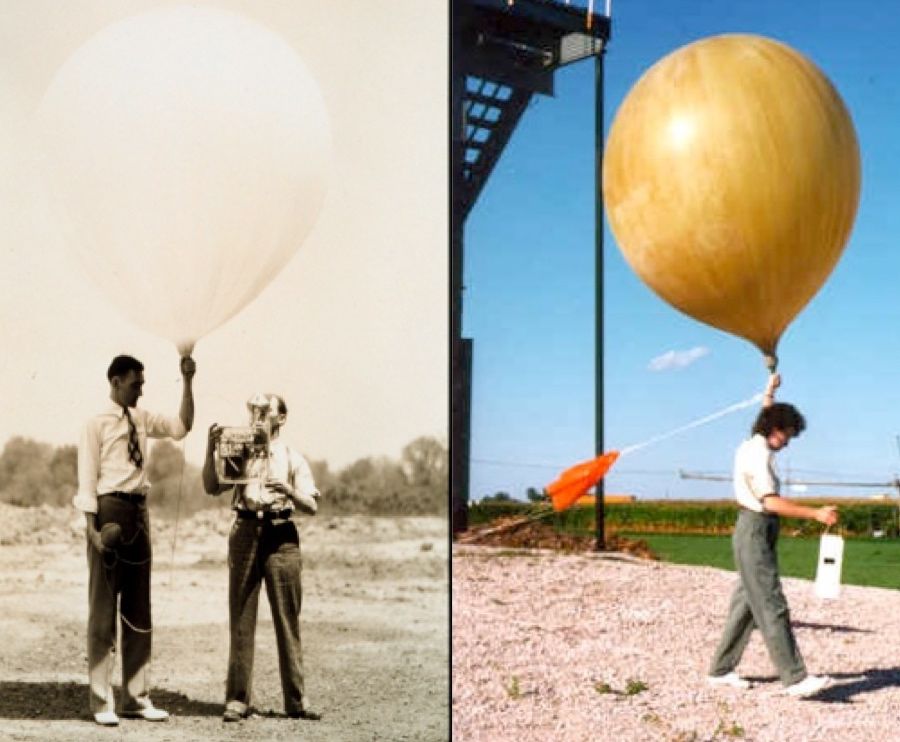

Weather balloon releases in 1930s and 1990s; technology, photography and clothing styles have changed, but these balloons have essentially stayed the same [Image Credit: NOAA National Weather Service]

Last year, on my birthday, around the time I was blowing out candles, about 900 balloons were simultaneously released from cities spanning the globe. What did I do to deserve such an honor?

Nothing at all. In fact, balloons are released on your birthday, too, not just once, but twice.

Weather forecasting today depends on intricate physics calculations and cutting-edge technology like Doppler radar, satellites and complex computer models, but one of its essential components is simple and centuries old: the weather balloon.

Weather stations all over the world release rubber balloons every 12 hours, at 6 a.m. and 6 p.m. Eastern Standard Time. When your computer screen warns of a severe-weather, tornado or winter-storm watch, that forecast usually depends on an extra balloon release from a location expecting bad weather.

A weather balloon’s measuring device, the radiosonde, which looks, from the outside, like a flimsy white, cardboard box, does what newer technology cannot. Hanging below the weather balloon, it takes measurements of temperature, pressure and humidity every second of its flight, creating a high-resolution picture of the atmosphere throughout space and time. Though satellites and radar can provide similar data, they cannot replace the radiosonde. “At the present time, there’s just nothing that has the vertical resolution of the radiosonde,” weather service meteorologist Bill Blackmore says.

Though it represents indispensable technology, the individual National Weather Service balloon has a short, disposable life. It starts as an inanimate, crumpled mass of plastic on a table inside what’s called an inflation shelter, a domed building with an antenna on top. As inflation begins, the balloon fills with helium or hydrogen and begins to rise from the table like Frankenstein (see videos at bottom of linked page). The release is just that, a person walking outside and letting go.

At release, the pressure of the gas inside the balloon matches atmospheric pressure, or about one bar, and the balloon is under five feet wide. As the balloon rises, the outside air pressure decreases, and the balloon expands until the pressure of the gas inside the balloon drops to match the pressure outside. The balloon continues to rise and expand until the rubber is stretched so thin — when its diameter is about 20 feet — that it finally bursts, at an altitude of around 20 miles and at a pressure of five to 10 millibars — nearly a vacuum.

“When they burst, they shatter,” Blackmore explains. “Since they are made from a natural compound [rubber], it disintegrates rather quickly into the atmosphere.”

Radio waves carry data from the radiosonde to a computer in the inflation shelter. Like weather balloons, which the weather service has used since 1937, these computers are classics. Seven stations in the U.S. still use IBM PC/XT computers, Blackmore says, which are over 20 years old and use five-and-a-quarter-inch floppy diskettes. Data from inflation shelters are then sent to supercomputers at the weather service’s Washington, D.C., headquarters. About four hours later, they, along with radar, satellite and other data from various sources, will have produced a local forecast.

Meanwhile, back in the atmosphere, the radiosonde falls back to Earth beneath a parachute. Radiosondes released in the U.S. come with a mailing bag and instructions for returning the device back to the weather service. About 20 percent of radiosondes are returned and refurbished.

The weather balloon and the radiosonde it carries aloft have celebrated over 70 birthdays of their own and have made no signs of retiring. Many happy returns.