Going green

The clothing industry prepares for an eco-friendly makeover

Susan E. Matthews • September 13, 2012

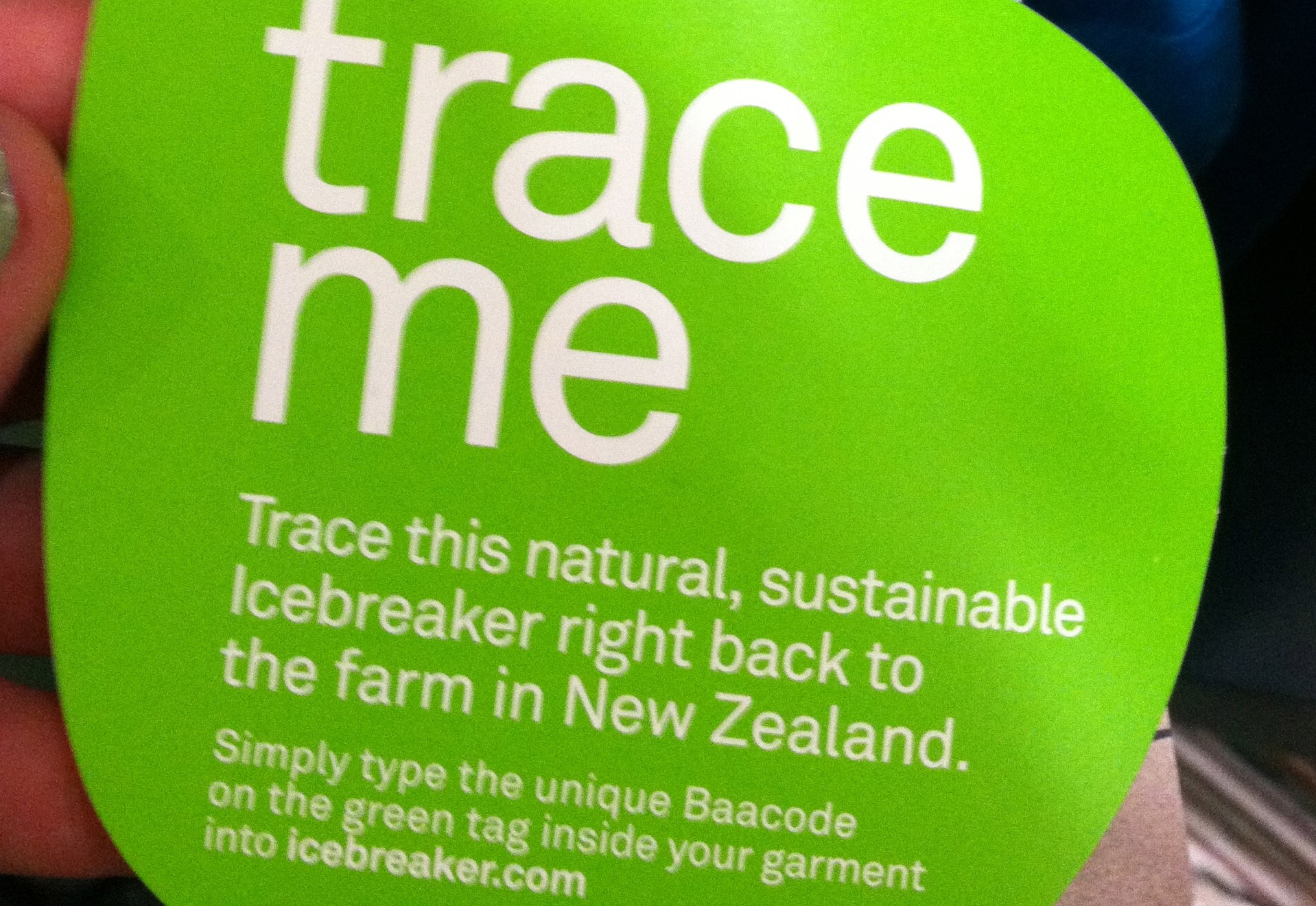

You’d buy an organic apple. But will you buy a sustainable windbreaker? [Image Credit: Susan E. Matthews]

Walk through any grocery store in New York City and advertisements touting various food products’ eco-friendly credibility will bombard you. From locally grown to organically farmed to wrapped in recycled packaging, environmentalists have officially co-opted the food industry. So what’s the next industry that may be going green?

Clothing. Some of the key phrases we associate with food and drink — local, organic, recycled — are also starting to apply to what we wear. But the process has been slow so far, because tracing all the components of clothing is more complicated than tracing an apple to its farm, for example. It requires assessing every production aspect (growing, dyeing, weaving, shipping) of all the fabrics and embellishments that make each item. Considering how much we buy, this might take a while.

In 2010, Americans spent around 340 billion dollars on clothing and shoes, more than we spent on cars, bottled water, video games and fast food — combined. The majority of this clothing is made in developing countries, where laws regulating the environmental impact of textile manufacturing are weak or non-existent. But as the desire to reduce our impact on the environment slowly goes mainstream, the demand for green clothing is rising. In response, the first trickling of green clothing is making its way from eco-friendly boutiques and outdoor clothing stores onto shelves at mainstream shopping destinations, such as Nike and H&M.

Demand drives economies. In the case of ecofashion, consumers must want (and be willing to pay for) green clothing for companies to develop it. Recent research has found that consumers say they’re ready to pay for sustainable choices. In fact, consumers may be willing to pay as much as $5 more for a $30 cotton shirt if the item is made organically, locally or through sustainable methods, according to a study by Jung Ha-Brookshire and Pamela Norum, professors of textile and apparel management at the University of Missouri. The two conducted a national phone survey asking individuals how much they would be willing to pay for greener clothing, finding that more than half of respondents said they were willing to drop an extra $5 for a greener product.

“[Consumers] want sustainability, but they want it at a low price,” Norum said.

Each production strategy — organically grown, sustainable or U.S.-grown — represents just one of many facets of green clothing. Organic cotton uses less pesticides, U.S.-grown cotton must adhere to environmental standards (which are higher than most developing countries’), and sustainable cotton’s growth can’t jeopardize the ability of future generations to use the land. Curiously, respondents did not show a strong preference between options. Consumers only want to know that a product benefits the environment, not how.

But are people putting their money where their mouths are? Not so much. In shopping for clothes, the decisions people make are affected by much more than price. According to another recent study, conducted by researchers at Open University in the U.K., people see their clothing choices as a physical manifestation of their identities. Clothing ties into consumers’ self-expression, and purchases are emotional, artistic choices that are frequently impulsive. The research found that even though consumers said they’d buy sustainable clothing, their shopping habits did not adhere to such standards.

Further complicating the problem, even if consumers committed to buying green, it would be difficult to know how. When a product is labeled “sustainable,” it’s tough to assess what that means, so already-reluctant consumers must invest their own time in researching products. “There aren’t any common standards,” according to Ha-Brookshire. “Everybody uses a different index or criteria.” And even when designers work in an environmentally conscious way, properly labeling products as “green” is time-consuming and costly. There’s no “USDA Organic” equivalent for the clothing industry.

“It takes more time and energy to develop the standards than it takes to do the right thing,” said an exasperated Ha-Brookshire.

The issue of how to label clothing for the public has puzzled eco-friendly designers for quite a while, with several options cropping up but eventually failing over the years, according to Tara St. James, a Brooklyn-based sustainable designer.

St. James is the main designer for Study NY, a brand that attempts to use sustainable and fair-trade fabrics and materials, garnering increasing recognition over the past few years. She previously designed for the eco-conscious sportswear label Covet, so she knows how difficult it is to design green, and she enumerates the reasons with a serious look in her frank, brown eyes. Most items require several types of fabric or material, each grown, dyed, spun and shipped from a different place. And there are so many options to choose from — organic, sustainable, fair trade, local, home-knitted, low water consumption, craft-made … her voice trails off without completing her list.

Labeling her clothing to explain its sustainability “would require a lot of tags,” St. James concludes simply. Rather than labeling, she has decided to maintain a blog where she writes about how she sources her clothing. She “tries to be as transparent as possible,” but recognizes that it takes a curious consumer to land on her site.

We’re in the Study NY studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn — a large warehouse-like room that is crowded, but not cluttered, with clothing and fabric. Even a glance around the studio confirms what she’s saying: “Clothing is a sum of many parts.” Each part requires the designer to make a careful choice between various pros and cons. Is it worth it to purchase fabric hand-knit by a co-op of women in Peru, even though the environmental costs of shipping to the States are substantial? St. James says that if she were to design using only local material it would severely limit her, and she finds value in supporting the Peruvian women’s business venture. Her mustard yellow plaid button-up contrasts oddly with gold nails that sparkle as she casually moves her hands to aid in her patient explanation of her work. Her outfit reminds me that, for designers, fashion is an intersection between business and art — designers are also artists.

While the number of small-scale eco-designers has steadily risen over the past decade, traces of environmentalism have found their way into larger clothing companies. American Apparel was built on the principle of locally made, efficient clothing production, with all of its factories based in Los Angeles. The company also occasionally uses organic cotton, although a visit to the 5th Avenue store yields only a few T-shirt packs bearing the neon green “organic cotton” sticker. “You could probably find more online,” an apathetic sales clerk tells me.

As frenzied shoppers flip through items on the sales rack at H&M, I scan for signs of the company’s recent Conscious Collection. The label is applied to clothing that “offers more sustainable fashion, both today and tomorrow,” according to the company website. The clothing I found sporting the Conscious label in the store was partially made from recycled materials.

“We noticed a growing interest from our customers,” public relations representative Jennifer Ward said of the line’s creation. The store has run a few collections that have been labeled as “conscious,” but an eco-friendly consumer would be disappointed at their 5th Avenue store — only a few items remained, scattered throughout the sales rack. It seems the line was popular, but it’s tough to tell if the “conscious” aspect had anything to do with it.

Nike has received recognition in recent years for reforming some of their production practices, culminating in the Nike Better World campaign (tagline: Kick ass … without kicking the planet’s ass). While every clothing item advertises the movement’s website on its tag, I had to ask seven sales representatives at the company’s main NYC store before finding one familiar with the line. He brought me over to a selection of women’s leggings, each apparently made using 10 recycled plastic water bottles. After taking a closer look at the tag, I realized they were produced in Sri Lanka.

The energy that it took to transport them to their current location far outweighed the savings of ten recycled bottles, which themselves may have been shipped to Sri Lanka to be turned into leggings. Purchasing them wouldn’t feel like I was doing the environment any favors, but water-bottle leggings may be preferable to cloth leggings — likely still made in Sri Lanka.

My leggings conundrum represents only a small facet of the many complications that are facing designers trying to turn the fashion industry green. Tough choices about what makes a product eco-friendly still haven’t been answered, and financing or marketing such ventures is still uncertain The industry is facing some tall orders as it steps up to the plate.

Even beyond these inherent challenges, there is a simpler hurdle to jump: Many consumers aren’t even aware of the work to be done, and instead over-consume the clothing that is so environmentally problematic. I saw this first hand when walking into Louis Vuitton: One associate simply blinked a few times at my query about green or sustainable clothing.

“Green,” she told me, “isn’t a prominently featured color in this year’s collection.”

Maybe next year.

1 Comment

Definitely Eco friendly clothing will help us It is a very good move.