Finding Philae: the case of the missing comet lander

Two months after its historic comet landing, Philae’s whereabouts are still unknown

Hanneke Weitering • January 15, 2015

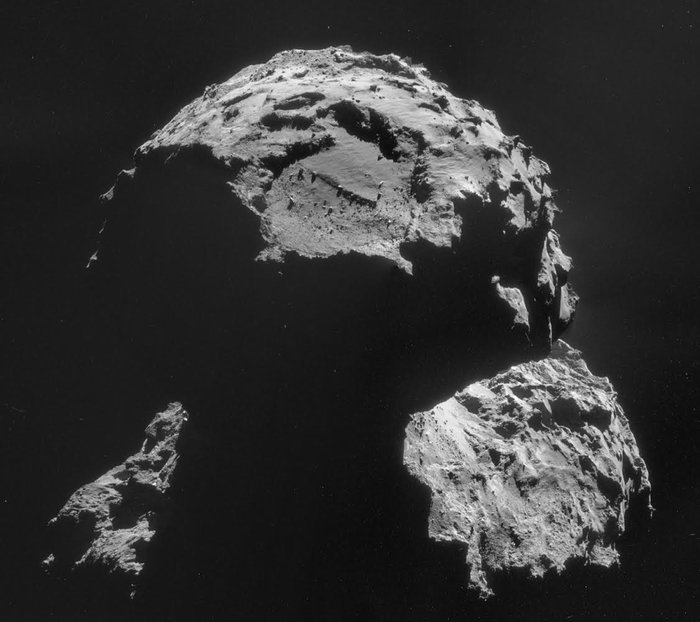

This image taken by the Rosetta spacecraft shows Philae’s intended landing site on Comet 67P. [Image credit: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM]

On the afternoon of November 12, the European Space Agency’s mission control room erupted in cheers when, for the first time in history, a spacecraft landed on a comet. Aiming the robotic lander toward a speeding space rock the size of Mount Fuji was no easy task for mission controllers, who sat more than 300 million miles away at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany.

Despite the mission’s success, however, there was just one problem: the Philae lander has gone missing.

Although Philae was successful in reaching Comet 67P, its landing was all but smooth. When Philae first hit the comet’s surface, it should have fired two anchoring harpoons into the soil and an additional thruster to hold it in place. But both the harpoons and the thruster malfunctioned, causing the lander to actually bounce off the comet and back into space.

The comet has such weak gravity — less than one in 100,000 times the Earth’s — that its escape velocity is only about one mile per hour. Anything traveling faster would never dream of staying put on that comet.

So Philae strayed an entire kilometer (roughly the span of the Golden Gate bridge) from the comet’s surface, but luckily the little comet had just enough gravity to bring it back down again. Almost two hours after the first touchdown, Philae was back on the ground — but not for long. The lander gently bounced one more time, though not nearly as high as the first time, before finally coming to rest at an unknown location a few minutes later.

The whole Philae fiasco was caught on camera by none other than Rosetta — the spacecraft that dropped off Philae and continues to orbit Comet 67P. Using Rosetta’s cameras, the ESA monitored Philae as it bounced over the comet. With these images, scientists hoped to guess Philae’s final location.

But efforts to pinpoint Philae’s current spot using Rosetta’s cameras have been unsuccessful. Although Philae was clearly seen bouncing all over the comet before, it’s much more difficult to spot the little spacecraft as it sits motionless on the comet’s surface. Given the resolution of Rosetta’s camera and its distance from the comet, Philae might only constitute one pixel in a photo of the comet, according to an ESA blog entry. Looking for Philae in these photos might be comparable to looking for a golf cart in a satellite image of downtown Los Angeles — a tedious if not impossible task.

So ESA scientists turned to the images and data transmitted by Philae itself. Unfortunately, they still weren’t able to determine its exact location. All they know is that it’s on the edge of a cliff somewhere in the dark. Without any sunlight to charge its solar panels, Philae’s battery quickly ran out, and the spacecraft went to sleep.

All hope is not lost for Philae, though. When Comet 67P nears the sun later this year, there’s a chance that some visible sunlight might recharge its batteries, and the ESA is confident the lander will eventually wake up. If and when Philae does come back to life, the lander should be able to communicate with Rosetta, allowing the scientists to finally find their missing spacecraft.

In the meantime, Rosetta won’t be taking any more pictures to try and locate Philae. Instead, the orbiter has other plans; it will venture farther away from the comet, where it will study the comet’s coma, or tail.

ESA scientists are still digging through the data captured during Philae’s 60 hours online. Although it’s far less than they had hoped, the “little lander that could” managed to return results from all 10 of its science instruments before slipping into hibernation.

2 Comments

Great article!!!

The whole Philae “fiasco”… rather a harsh word for such an amazing overall achievement.