Ig Nobels fail to bring a key field to view

Missing microbes on science’s goofiest day

Meghan Bartels • September 22, 2015

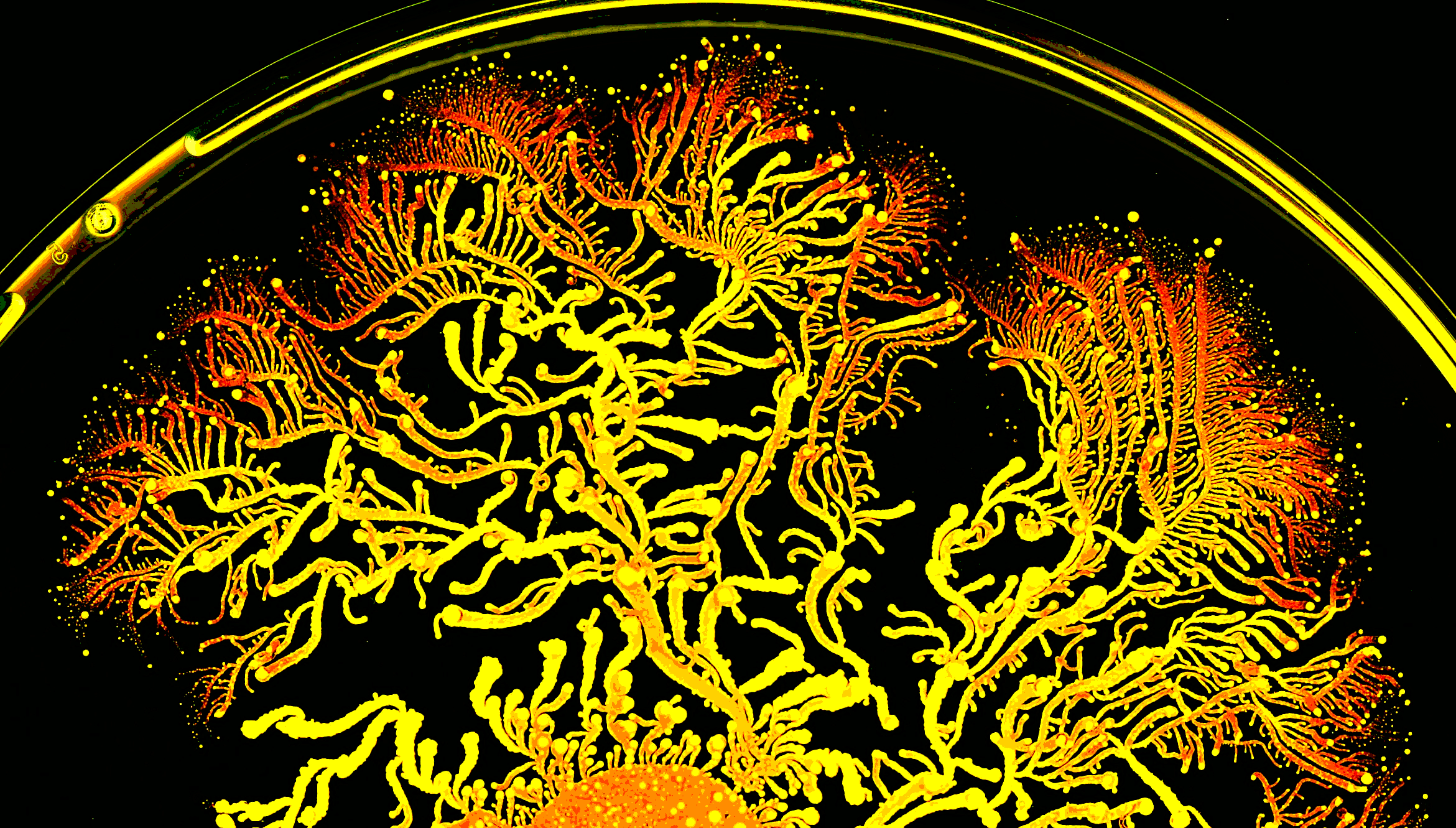

A colony of Paenibacillus vortex. [Image credit: Wikimedia Commons user Paenigenome]

Can you diagnose appendicitis with a speed bump? Can you unboil an egg? Can you make a chicken walk like a dinosaur? These feats may sound kooky, but they were real scientific studies that received Ig Nobel Awards last week.

The ceremony, an annual Internet favorite when science flaunts its sense of humor, highlights “research that makes people LAUGH and then THINK,” according to the organizers: a group of scientists, science writers and others. But there’s a huge, and hugely important, field of research that has been starkly absent from the awards: microbiology. Not since 2010 has this tiny squirmy science — which studies bacteria, fungi and viruses — had a turn in the spotlight. That year, a team of transportation engineers won for recreating the Tokyo transit network with a slime mold. The previous year, scientists were recognized for coaxing bacteria from panda poop into munching most of a pile of kitchen waste. Both these studies harnessed the talents of microbes in unexpected ways with genuine practical implications.

Of course, it is wrong to laugh at the microbes that cause diseases and otherwise make people’s lives harder. But surely a field that includes brewing alcohol and fecal transplants deserves a little thoughtful humor every couple of years.

It’s not about the 15 seconds of fame. In a culture where science is often considered intimidating and the stereotype of the mad scientist still has influence, it is more important than ever to remind people that scientists are real people who are curious about even the wackiest parts of their fields. While the Nobel Prize brings groundbreaking research the respect it deserves, the Ig Nobels offer approachability and a path from laughter to greater engagement with science.

There is a consensus that scientific literacy in the U.S. isn’t what it should be. Just last week, the Pew Research Center published a short quiz of more than 3,200 American adults answering 12 relatively basic science questions. The average score was an eight, and not one demographic pulled off an 11 or 12. Other surveys over the past four years have found that almost two-thirds of American respondents could not name a single living scientist, and that when asked to name any scientist, almost half chose Albert Einstein, who died in 1955.

A basic understanding of modern science isn’t just nice to have: Microbiologists are tackling issues that not only impact the public, but rely on public cooperation — not to mention funding — for the best possible outcomes.

The World Health Organization has declared the rise of bacteria that can shrug off one or more drugs a “serious, worldwide threat to public health.” But slowing the spread of resistance requires everyone, not just scientists. This week, scientists reminded us that soap containing antibiotics is no better at stopping germs than normal soap, but many consumers are still comforted by the mirage of more dead bacteria. As winter approaches, parents will go to doctor’s offices asking for something, anything, to clear their child’s undiagnosed infection, and many will walk away with broad-spectrum antibiotics. The more times bacteria are exposed to drugs like these, the higher the probability a bug will become immune to them and pass the resistance on to its offspring.

The issue is put in even starker terms by what many Americans were watching while this year’s Ig Nobels were announced: the second Republican presidential debate, during which several candidates repeated the false claim that vaccines cause autism. It has been less than a year since a measles outbreak, attributed in part to parents who willfully ignored vaccine recommendations, infected 131 people and tarnished Disneyland’s reputation as the happiest place on Earth.

Getting the most out of antibiotics and vaccines is one of the most tangible goals of microbiology. When communication breaks down even about topics like these, it’s clear there is a problem. Seeing microbiologists dress up as their research project and receive a flowerpot at the Ig Nobels is not a magic wand. But when the judges include categories at their whim and the cost is so low, what’s the harm in trying? Next year, I’m hoping to see some fun scientists dressed like fungi.

1 Comment

Hi. I’m the founder of the Ig Nobel ceremony. Nice article! You may not know that last year the mini-opera in the Ig Nobel ceremony featured The Microbe Chorus. The mini-opera way back in 2010 was al about microbes. http://www.improbable.com/ig/archive.html