The final frontier?

Mars may be our next step, but Louis Friedman says it may also be our last

Michael Koziol • February 7, 2016

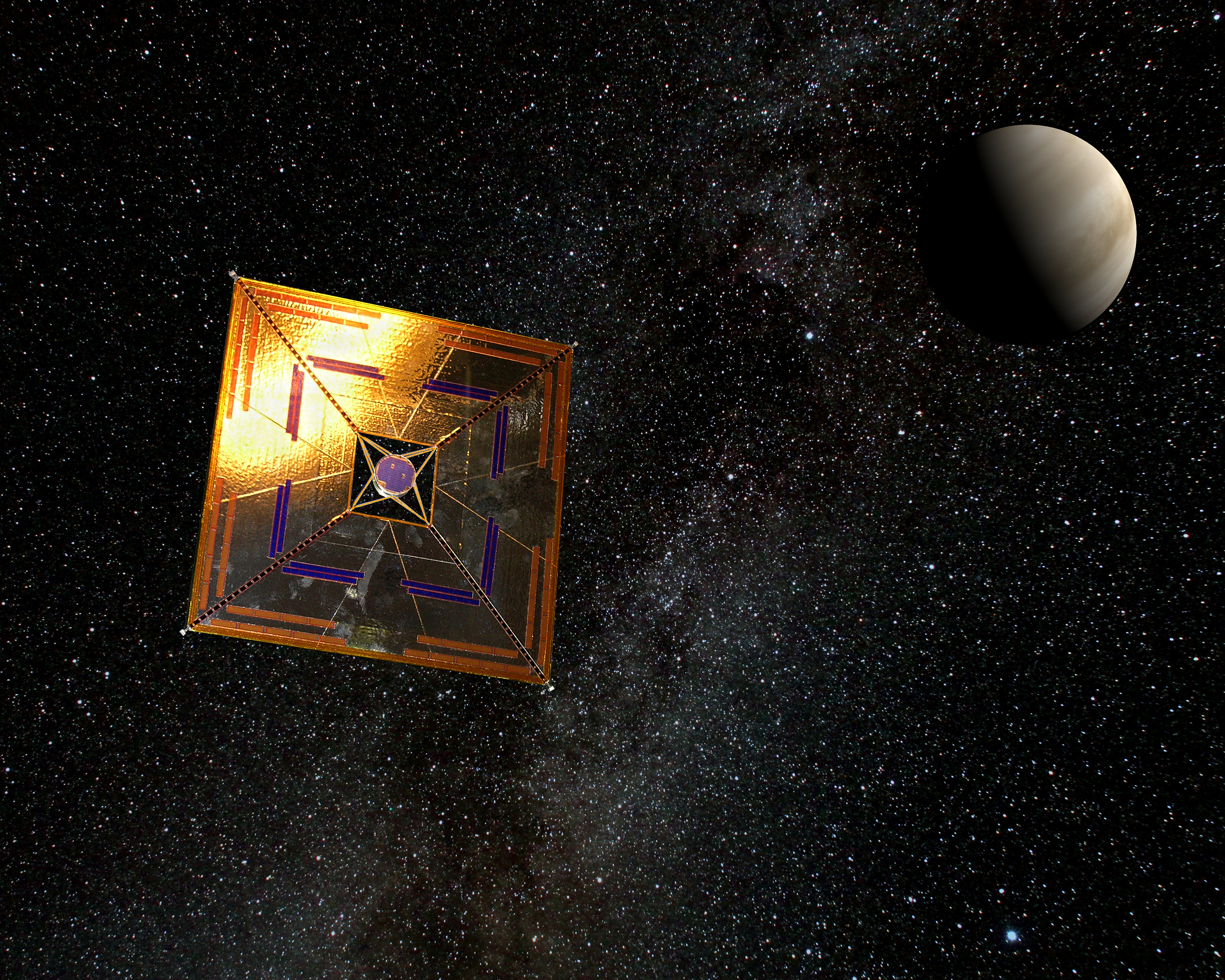

Our future in space may be robotic, like this theoretical probe powered by solar sails, which could send robots far beyond where humans will ever go. [Image Credit: Andrzej Mirecki, CC BY-SA 3.0]

He’s spent more than 40 years sending machines into outer space, but Louis Friedman isn’t ready to write off human space exploration quite yet — on Mars, at least.

“Are we to be satisfied only virtually?” he asked at a recent talk at the American Museum of Natural History, letting the question hang for a few seconds before answering in the negative.

The more important question, he thinks, is whether Mars will be our last stop. After that, he believes, robotic spacecraft will likely take over, pushing the boundaries of our presence in the universe through their cameras and probes.

If anyone knows deep space robotics, it’s Friedman, 74, who has worked on almost all the famous deep space missions: Mariner, Voyager, Galileo and Magellan, to name a few. In 1980 with Carl Sagan and Bruce Murray, he co-founded the Planetary Society, an organization dedicated to popularizing the idea of exploring new worlds.

So it may come as a surprise that Friedman doesn’t advocate for human exploration of those new worlds. In his Oct. 19 talk at the museum, he gave a sold-out crowd his vision of the future. For him, robots will dominate our future among the stars. He’s watched the field of robotic exploration develop at a tremendous pace while the technology for human exploration has lagged. He points to NASA’s space suit design, which hasn’t changed drastically in 60 years, as one example.

In the next 60 years, Friedman sees a future of manned Martian exploration augmented by deep space robotic probes thrust forward by solar sails, massive sails that would rely on energy from the sun’s light to gradually push the probe to high speeds. His crucial argument, though, is that our exploration and eventual colonization, will take so long — centuries, maybe — that by the time we’re ready to take the step beyond Mars, our ability to probe the universe robotically will be so far ahead of our manned exploration capabilities that we will be content to remain a multi-planet species of two worlds — but multi-planet nonetheless.

Considering the developments in human and robotic exploration over the past few decades, it may be the logical conclusion, but not everyone holds the same opinion as Friedman. “It’s a potential future, it’s foolish to deny that,” says Ian Crawford, a professor of planetary science and astrobiology at Birkbeck University of London, who resigned from the Planetary Society due to disagreements on the future of exploration efforts. While Crawford wants to send humans to space, the Planetary Society is instead focusing on developing its solar sail project, LightSail, emphasizing a robotic future for deep space exploration. Crawford believes that stopping human exploration at Mars won’t be enough, especially if you treat it as the last step. “Once you decide that Mars is the ultimate step, it’s a mindset that can give a dead end.”

Crawford agrees that the first step into any new region of space will begin with robotic explorers, but that we won’t remain satisfied there. He says there are more important — if intangible — reasons to set foot beyond Mars. “If you want to broaden human horizons, the more people you have in more places having literally different worldviews,” the richer all of our lives will be.

There are also less philosophical considerations at play when it comes to the future of space exploration. At the talk, Friedman suggested that private companies like SpaceX are more likely to take over the task of low-Earth orbit development — such as launching satellites — as they develop their capabilities, allowing NASA and other government space programs to push out further, although NASA and SpaceX have already discussed potential plans to use a variation of the latter’s Dragon capsule to reach the Martian surface. Crawford agrees in the short term, but believes that humans will be drawn further into space by the desire to explore. Eventually, he says, scientific research will piggyback on space infrastructure built for tourism and commercial reasons, just as today a scientist will take an airplane to do field research in another country.

When it comes to matters of exploration, though, Friedman stuck to his argument: By the time we’re ready to go beyond Mars, no one will want to. “Unless you’re a particle physicist interested in individual molecules, there’s not much out there.”

Friedman acknowledged that an exclusively robotic vision of exploration can seem bleak, relegating our species to just two planets with no intention of pushing further out. But he believes our mindset will change and we will be satisfied leaving the exploration to robots. He already sees people becoming content to stay closer to home. He told the audience a story about asking his grandson why he never saw him talking with friends. His grandson responded that he did a lot of socializing, but most of it was online.

As we develop our capabilities for space travel, Friedman says, we will also extend our comfort with experiencing things virtually. “I suggest to you we do have a bright human future in space,” Friedman said as a conclusion, “We’ll be out there in space with our minds, and with our bodies on two planets.”