The surprising history of π

Actually, it’s not all that Greek to me

Meghan Bartels • March 14, 2016

Pie pi is clearly the tastiest way to represent pi, but what’s the oldest? [Image credit: Kristin Brenemen | CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

The Greeks get a lot of credit for a lot of things, but that doesn’t always mean they deserve it. Take π, that magical number that turns a circle’s diameter into its circumference: It’s designated by a Greek letter and that Archimedes guy estimated it with some polygons, so it must be Greek, right?

Wrong.

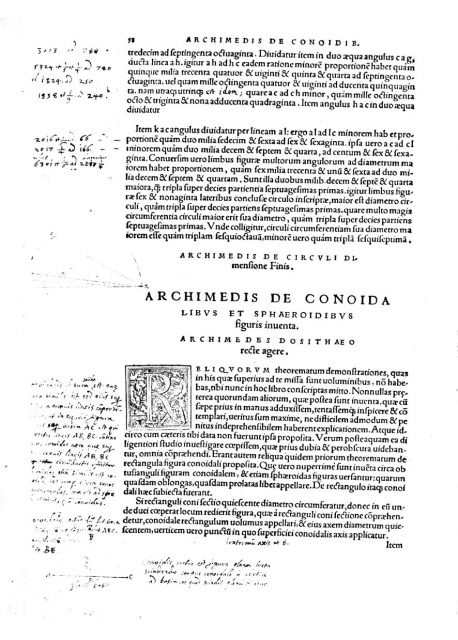

Sure, this is (a much later, printed Latin translation of) Archimedes calculating π — pretty accurately, no less, but let’s not get too excited. [Image credit: Biblioteca Europea di Informazione e Cultura | CC BY-NC-ND 3.0]

For most of history, π wasn’t really represented by any particular symbol at all. Like Archimedes, many mathematicians just wrote out what they were talking about, using whatever variation of “the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter” they happened to prefer. Otherwise, they just used the current numerical approximation. Three was a popular simplification, but many estimates were actually quite close to the value we know today.

And even when mathematicians finally decided it would be handy to have a standard symbol, there were a few other contenders to fill the role of what became π.

![John Wallis uses a square to represent the ratio of a circle’s area to the square of its radius. [Image credit: Archive.org | public domain]](https://scienceline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/02_ArithmeticaInfinitorum_0201_-640x208.jpg)

John Wallis uses a square to represent the ratio of a circle’s area to the square of its radius. [Image credit: Archive.org | public domain]

![In which William Jones can’t quite decide if he wants to invent π. [Image courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Bangor University]](https://scienceline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/03_Ann201-355x640.jpg)

In which William Jones can’t quite decide if he wants to invent π. [Image courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Bangor University]

![William Jones gets down to business, saving future mathematicians from representing a number with a clunky phrase. [Image courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Bangor University]](https://scienceline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/04_Ann203-349x640.jpg)

William Jones gets down to business, saving future mathematicians from representing a number with a clunky phrase. [Image courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Bangor University]

But even once π was the undisputed symbol for the ratio between a circle’s circumference and diameter, there was still the tricky matter of actually remembering the number it represented. One popular approach was to compose mnemonic devices, often structured so that the number of letters in each word matched each digit of π, a strategy called pilish. There are dozens of examples in languages from Albanian to Swedish.

English speakers may particularly enjoy this charmer, published in the magazine of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. The editor suspected it was submitted by a famous astronomer of the time, who noted it had been tailored for an American audience. “How I want a drink, alcoholic of course, after the heavy chapters involving quantum mechanics.”

Now π is second nature to us, but next time you find yourself impatient with calculations, spare a thought for the mathematicians who spent millennia doing math with words instead of symbols and raise your glass to π!