Where the hell is everybody?

The Universe is probably devoid of life, but experts say we may never be sure

Dan Robitzski • October 17, 2016

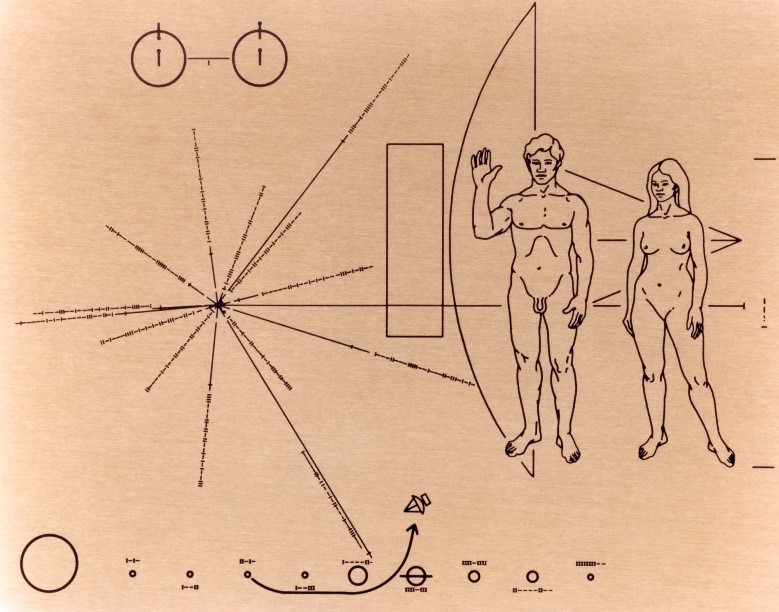

Our farthest-reaching messages, like this plaque on Pioneer 10, have barely penetrated the vastness of space. Even if complex life forms are out there, would they notice? [Image Credit: NASA-Ames Research Center | CC0]

A heavy bass line from DJ Black Helmet’s latest set — a mashup of jazzy throwbacks and new-age fusion — hit me as I walked into the room. I was surrounded by cool-looking Brooklyn millennials, clad in leather jackets and bleached hair.

Someone in this room was going to wax philosophically on life — what it means and where it comes from — but it wasn’t going to be the buzzed hipsters. I was at Pioneer Works, a non-profit art museum and science outreach center in Brooklyn, to listen to some award-winning scientists and professors contemplate perhaps the biggest question there is: Are we alone in the universe?

It turns out that even three of the leading experts on extraterrestrial life can’t give definitive answers. But their panel, held during the Scientific Controversies event on October 6, fostered lots of speculation.

When it comes to the search for complex extraterrestrial life, researchers aren’t sure what to look for. There are clues: If we see carbon-based organic molecules, the building blocks of life on Earth, on another planet or moon, then it might mean that life could exist there. But there are many steps and a whole lot of sophisticated organization between simple carbon molecules and living cells, so carbon’s presence is not enough.

Life has managed to permeate all of the environments of earth — even the coldest, hottest, deepest and highest — and many of those extreme environments could be compared to known extraterrestrial phenomena, according to one of the speakers, Nick Lane, evolutionary biochemist at University College London. Citing the vast array of “inventive biology” on Earth, Lane argued that it’s a reasonable assertion that life’s basic components on other planets would be fairly similar. However, researchers don’t have the tools to determine the probability or mechanisms by which those raw materials might form life.

The abundance of these earthlike conditions, which according to Lane may exist in as many as one-fourth of the likely billions and billions of planets in the known universe, often lead people to assume, statistically, that extraterrestrial life must exist. But Lane questions that assumption. “It seems like a no brainer that there’s got to be life out there,” he said. “This is part of the problem. We don’t have the statistics for that kind of big number.” He’s more optimistic about the generation of organic carbon, the key building block of life on Earth, but doesn’t extrapolate to the complexities of cellular life. “Carbon is the easy part,” he said. “It’s everything beyond that that’s more difficult.”

The big challenge in assessing whether a planet is likely to contain life is that there are no examples, other than the nebulous beginning of life on Earth, to use as reference. There are many good ideas on how cellular life began, and then later made the leap to multicellular organisms, but because these developments only happened once in known history, there’s no way to come up with predictive models. “How do you assign probability to a seemingly random event?” was the big question posed by Caleb Scharf, an astrobiologist at Columbia University. He argued that observations on how life began could not be applied to other situations because all of our data was collected retroactively. We understand many of the conditions that were conducive to developing life on Earth, but Scharf explained that it’s impossible to tell whether these conditions will generally give rise to living organisms or if the beginning of life was something of a fluke.

If there is life out there, there is also a good chance that we will never find it. “We keep expecting humanoid life, but look at all the things on our planet that have been around much longer than us,” said the panel moderator, Janna Levin, the science director at Pioneer Works and an astronomer at New York City’s Barnard College. Scharf agreed, quipping “I have no bloody idea what an alien would look like.” Lane added that because humanity’s intellectual abilities may be more of a freak accident than an evolutionary inevitability, any alien life that’s out there might be unable to explore the planets or respond to our search.

The panel, in their discussion of evolutionary biology, pointed out that life will do what it must to adapt and survive, but nothing more. So the odds that another species would develop the intelligence to be able to detect or transmit messages into space are astronomically low. Fermi’s paradox postulates that if an intelligent and advanced species was capable and motivated to traverse the galaxy, they would already have done so.

And even if intelligent life has developed, it’s unlikely that we will come across it, the panelists agreed. Just as it’s uncommon for a species to face environmental pressures to develop advanced intelligence, it’s even less likely that it would need to adapt to space travel. “Biology as we know it is lousy for that, and machines are more likely to be successful” said Scharf. It is more reasonable to expect an interaction of robotics than to see extraterrestrials up close, he added.

The Breakthrough Starshot Initiative is developing a plan to explore the star nearest our solar system, Alpha Centauri, by launching tiny vessels at roughly one-fifth the speed of light. These machines would fly through the star system and transmit their findings back to Earth. So if we are sending robots out into space, why would we expect aliens to do any differently? A swarm of tiny robots would likely be undetectable by any live organisms in Alpha Centauri’s solar system. So if extraterrestrial organisms developed the same strategy, “these things could be zipping past us all the time and we would never know it,” Scharf noted.

Even though we’ve landed rovers on Mars and launched missions elsewhere, the prime objective of these expeditions was rarely to scan for life. “We just haven’t looked closely. We’ve sent the wrong kind of missions,” Scharf said, pointing out that scientists could readily develop different kinds of missions that would be better suited for the task. Levin played an animation demonstrating the scale of the known universe, which is so vast that our galaxy wasn’t even allotted a single pixel. “We’ve only been to the moon. That’s not to be slighted, but that’s it. Our farthest-reaching satellites have only just broken out of the solar system,” Levin said.

Considering that small scale, it’s important to note how significant it would be to find even a single cell outside of earth. “We only have one data point, and extrapolating from that is extremely difficult,” Scharf said. “But all it would take is one instance of life to shift those statistics totally in favor of a universe teeming with life.” It’s hard to imagine, but for all we know there could be another museum, somewhere on the far side of the universe, that’s packed with hip, young aliens theorizing our existence.

4 Comments

That’s crazy. Just goes to show you that “God” probably doesn’t even exist.

I have to admit, you changed my mind a few things!

If they found life on Saturn’s moon, then why not somewhere else in the galaxy, let alone universe!

Life and intelligent life may be so rare in our minuscule time scale that it never exists in more than one place at the same time and there may be immense stretches of time when there is no life, anywhere. It’s possible aliens just visited us in the recent past, or will in the immediate near future (say, 100 million years either way).