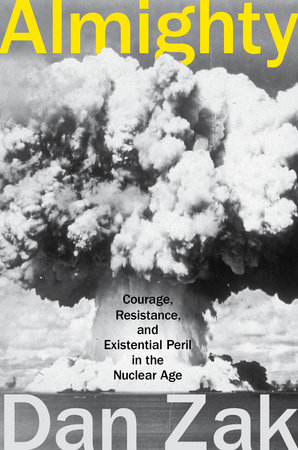

Washington Post reporter Dan Zak’s first book tackles some of the modern era’s biggest issues, the size evident even in its title: “Almighty: Courage, Resistance and Existential Peril in the Nuclear Age.”

At once a deft profile of anti-nuclear activists and a supplement to traditional history books that often leave out the multi-varied perspectives on the end of World War II, the book makes the compelling argument that we must bring the good, the bad and the ugly aspects of nuclear weapons to the forefront of our national conversation.

Q: Why aren’t nuclear weapons more commonly discussed?

Well, I’ve thought a lot about this and I have some theories. One is very simple, and that is, [nuclear information] is highly classified.

A more cosmic reason is that it is difficult to think about what a nuclear weapon can do and what nuclear war can do and what’s at stake.

It’s also hugely depressing and fatalistic. I mean, why would you want to think about the risks and the consequences of this when it seems like a problem that’s so out of reach?

Also, the very obvious reason that the Cold War has been over for over 25 years and you no longer have this force that makes people incorporate that fear into their daily lives. There are now multiple generations who have not experienced “duck and cover” and who have not experienced Cold War-like tensions between superpowers with unimaginable stockpiles.

Q: Why have anti-nuclear protests decreased [since the 1980s]?

Today [activism] can feel very anachronistic to a lot of people, especially if it’s activism practiced by older people whose tactics haven’t really changed. These people I wrote about in this book — and this is not to demean them — do this kind of “old school” activism that younger generations have not been exposed to or practiced, and so it seems very antiquated, I think, and that can be further alienating. “Oh, these are just hippies that are left over from the ‘60s and ‘70s and ‘80s, and they clearly haven’t moved on when the rest of the world has.”

Also, since this anti-nuclear activism in the ‘40s and ‘60s and ‘80s, there have been increased opportunities for people to get graduate degrees in arms control, to choose, if they want to make change, to choose an official path, get inside the system and try to work for change inside the system.

Q: Do you see my generation, as a whole, taking this issue on?

If you had asked me three years ago maybe, or two years ago, even, I would have said, “I don’t see that.” But then I went to a couple conferences where the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, called ICAN, was involved and I just was totally shocked at the numbers and intensity of youthful participation there. There were Americans, but it mainly young people from other countries, especially Europe, who were my age and younger and who were knowledgeable and passionate about this topic. Until I went abroad, I didn’t think it was a youthful thing, and then I saw there were people who were very animated, people from non-nuclear states, who believe that the nuclear powers are really holding back progress and putting the world at risk.

Q: So where are the American youth in this?

I think if you were to go — and I’ve seen activist videos do this — to Capitol Hill and find congressmen and women and ask them, “How many nuclear weapons does the U.S. currently have?” I bet 99 out of 100 would not even get close to the right number. So when you have elected officials who just don’t know, that sets a tone, and you’re not going to necessarily have an informed citizenry.

President Obama has been pretty good about talking about it, but even that is always with the caveat that we need them. We need to get rid of them, but we need them as well. It’s not necessarily as motivating as living in Austria and having your foreign minister say, “We need to ban these weapons because they’re illegal under international law.” So it’s just a different tone in the U.S.

Q: How have readers responded?

Anecdotally, I’ve heard from people around my age the same reaction I’ve had, which was complete shock at how much I didn’t know. The research and reporting process for me was a constant series of shocks and feelings of guilt that this consequential strain of American history was so unknown to me.

Q: If no one knows much about nuclear weapons, how, at the same time, does everyone have such strong opinions about whether or not we should have them?

I’ve had heated exchanges with people in Washington [D.C.], especially official Washington, about why we need these weapons. I’m not about to issue some opinion about “We should do this or we shouldn’t do this.” I just think it’s worth asking a bunch of critical questions and looking at something from all sides. And I just think when you challenge that [worldview] it can be very upsetting to [opinionated people’s] logic and, I think, to their emotions and their view of their own country.

Q: To a degree now, you’re no longer a lay person on nuclear topics, you’re, let’s say, a “lay expert.” How does that shape the way you communicate these ideas?

People ask me, “So, OK, are you for nuclear weapons? You must not be against them, because you’re writing about these activists.” And I always answer with, the one thing I can objectively state, after four years of thinking and researching and writing about this, is that I think the objective truth is that human beings are flawed and make mistakes, and perhaps we are not wholly capable of handling this ultimate power with 100 percent safety and security all the time. And then we need to ask, “Are we ok with that risk?” The risk is small, but “Are we comfortable taking this gamble with ourselves?”

Author’s note: This conversation has been edited for concision and clarity.