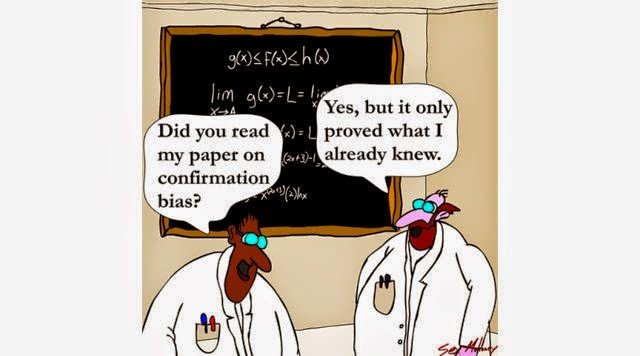

You’re not nearly as rational as you think

Confirmation bias might even apply to decisions we think of as purely objective, like math problems

Dana Najjar • November 29, 2018

While debates rage over possible biases behind Facebook and Google’s news feeds, the reality may be that it matters less than we think. Source: Peter Dashevici, Creative Commons

We all like to think of ourselves as eminently rational. Sure, everyone’s susceptible to a little bit of bias, but at the end of the day we’re capable of making purely rational decisions.

Or are we?

One bias in particular — confirmation bias — might be especially difficult to overcome, according to a new study that sheds light on how our brains can trick us into getting things wrong.

Confirmation bias is the psychological drive in all of us to seek out and warp new information so that it strengthens pre-existing beliefs. It’s partly to blame for the perpetuation of stereotypes and for your uncle’s solemn conviction that women are bad drivers despite all evidence to the contrary. The driver who cut him off yesterday? Proof positive that women can’t be trusted behind the wheel. But that woman who flawlessly parallel parked? Definitely a fluke.

The study, published September in the journal Current Biology, suggests that confirmation bias applies not only to abstract or high-level thinking, such as scientific reasoning or political affiliation — or, yes, automotive judgment. It also applies to so called low-level decision-making that seems, on the surface, completely objective.

“This type of bias has been documented in high-level reasoning tasks. We wanted to know if it generalizes to low-level judgments,” said Tobias Donner, a neuroscientist with Germany’s University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf and a lead author on the paper.

Study participants watched a movie of white dots moving on a computer screen and were asked to decide whether the dots were moving clockwise or counterclockwise (not as easy as it sounds, since the dots were surrounded by other randomly moving dots). Next, they watched a second movie of animated dots. They were then asked to determine the overall direction of motion for both movies.

Researchers found the participants’ first decision biased their judgment about the second; those who had started out by saying clockwise were much more likely to stick with that direction regardless of what came next, and vice versa. The findings were validated in a second experiment that asked participants to estimate the average of a series of numbers.

Were the participants devaluing information that disagreed with their initial choice, or did they simply not see it? The researchers believe the latter mechanism is at play, that the participants selectively paid more attention to new data that agreed with their initial choice and ignored those that didn’t. “As we commit to a particular judgment or hypothesis,” said Donner, “this acts in the brain as an attention cue,” modulating what we pay attention to and, as a result, what we see and what we don’t.

This is a whole new understanding of how confirmation bias works. Rather than taking in all available information and selectively analyzing it, our brains may be leaving out anything that disagrees with our previous judgments right out of the gate.

“This is kind of scary,” said Jaime de la Rocha, a neuroscientist at the Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute in Spain who wasn’t involved in the study. “When people are evaluating evidence, they are using a filter created by previous decisions.”

So do we stand a chance against this particular bias, or should we resign ourselves to remaining entrenched in our beliefs?

De la Rocha isn’t sure. “There is no magical formula to avoid bias,” he said, and “it’s too early to know if we can override it.” But if he had to guess: “It seems like this is low-level – the kind of stuff that you cannot avoid.”

Donner, however, is more optimistic. He said he thinks any decision-maker can try to counteract the effect of confirmation bias by actively directing their attention rather than letting their past choices direct it for them.

“Having made a choice, pay extra attention to things that contradict that choice,” he explained. This may seem obvious, but it requires working hard against what appear to be very deep-seated cerebral mechanisms, and that’s no easy feat.