The next-next-generation of exoplanet astronomy

As the long-awaited launch of the James Webb Space Telescope approaches, astronomers just picked its successor’s successor.

Allison Parshall • December 13, 2021

Natalie Batalha (center) discusses the future of exoplanet astronomy at a panel discussion with fellow astrophysicists Rebecca Oppenheimer (left) and Janna Levin (right). [Credit: Ester Segretto, courtesy of Pioneer Works]

When it comes to exoplanet discovery, Natalie Batalha was there for the beginning. A young astrophysics grad student in 1995, she happened to be attending a conference in Florence, Italy in place of her advisor when two astronomers announced the first discovery of a planet orbiting another star like our sun.

“An entire new subfield of astrophysics was being born,” recalls Batalha, who went on to become the project scientist for NASA’s Kepler Mission, which identified the first rocky planet outside our solar system in 2011. Now an exoplanet researcher at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California, Batalha has since become one of the leaders in her field.

The next milestone in the search for exoplanets is now upon us: the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope. As the successor to the surprisingly durable but more limited Hubble Space Telescope, Webb was originally set to rocket into orbit around the sun as early as 2007. It is scheduled to finally launch this month.

The telescope’s infrared capabilities will allow scientists to analyze the atmosphere of faraway planets better than ever before. When light passes through the atmosphere of a planet, it takes on the “chemical fingerprint” of the elements present in that atmosphere, Batalha explained at a recent panel discussion on exoplanets at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn.

From this data, scientists are hoping to identify some of those fingerprints as signs of life. If they exist, researchers expect to spot them by picking up evidence of biological waste products in the atmosphere. “I’m hopeful that living worlds are going to stick out like a sore thumb,” said Batalha, who is on the Webb Telescope’s Advisory Committee.

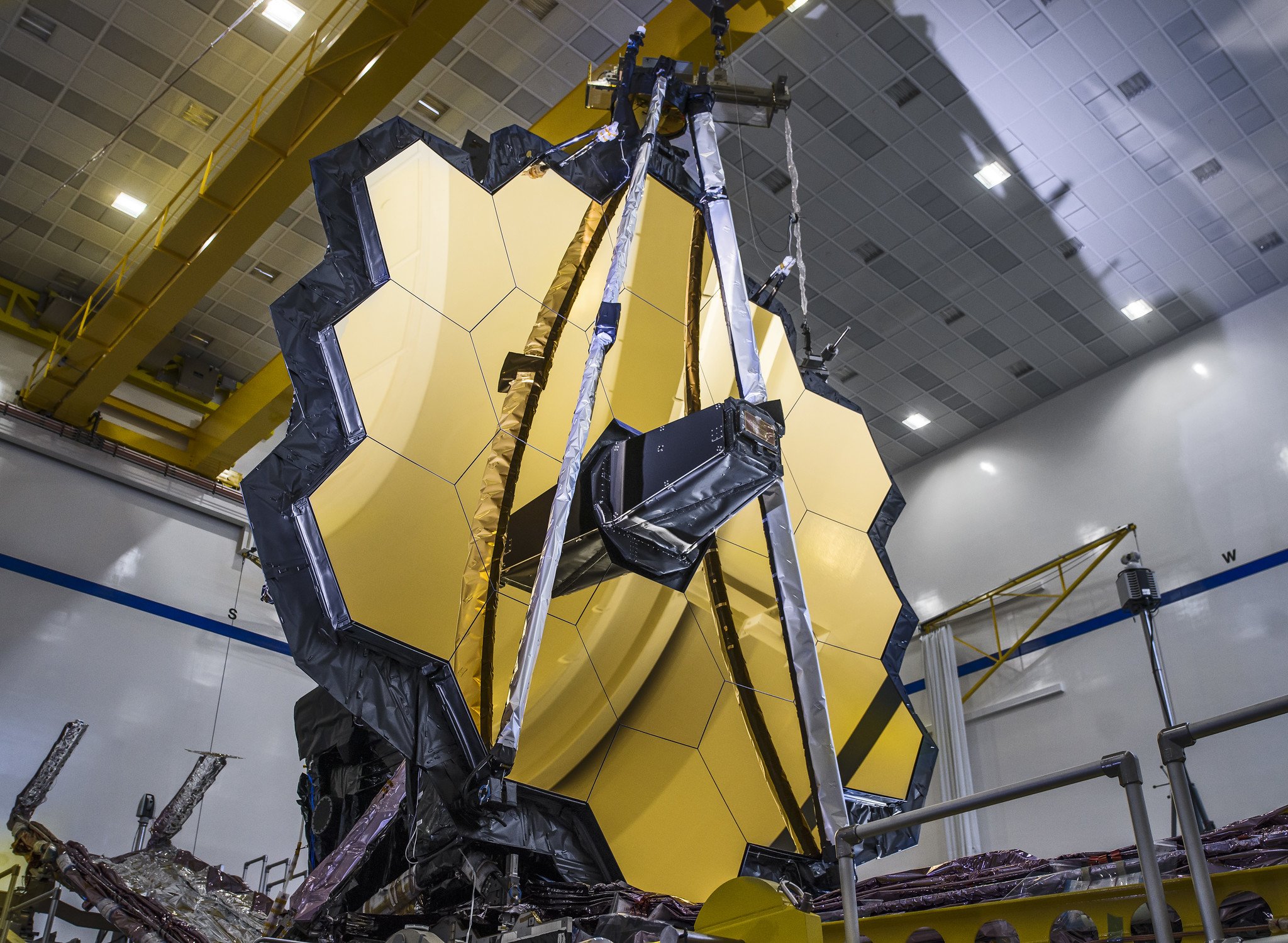

The James Webb Space Telescope is set to launch this month. It will, amongst other functions, analyze the atmospheres of distant planets outside our solar system. [Credit: NASA/Chris Gunn | CC BY 2.0]

But even as they await Webb’s long-anticipated launch, researchers are already planning decades into the future. Engineers will soon begin building Webb’s successor, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. And in early November, the results of the astronomical community’s once-a-decade survey were published by the National Academy of Sciences, which considered four concept designs for the next flagship telescope.

“I was on pins and needles to know if they were going to pick my favorite,” Batalha said. Her favorite design — called LUVOIR — had a 15-meter-diameter mirror and would, if chosen, have been capable of detecting signs of life on a few dozen distant planets. It could have cost as much as $24 billion. The survey committee ultimately recommended a design inspired partly by LUVOIR, with a six-meter-diameter mirror to decrease the price tag to $11 billion.

Batalha wasn’t thrilled about the downsizing, worrying that a smaller mirror will limit the number of exoplanets the telescope will be able to observe. Still, she called it “a decent compromise,” adding that, “in your lifetime or the lifetime of your children, we could know of another living world.”

This orbiting observatory won’t launch until the late 2040s at the earliest. In a field that must think so far in the future, Batalha has had to reckon with the knowledge that she will see very few of her many questions answered in her lifetime. “I seek solace knowing my daughter is an astrophysicist,” Batalha says. “She’s totally my upgrade.” Her daughter, Natasha Batalha, leads a NASA Ames team that was awarded the largest exoplanet observation program for the Webb telescope.

For now, Natalie Batalha still seeks the answers to those big questions: how we got here, if we’re alone, and what it all means. “I live my life, and I do my profession, as if all the mysteries are knowable,” she said at the panel discussion. And looking out at the coming generations — of telescopes and of scientists — at least some of them certainly will be.