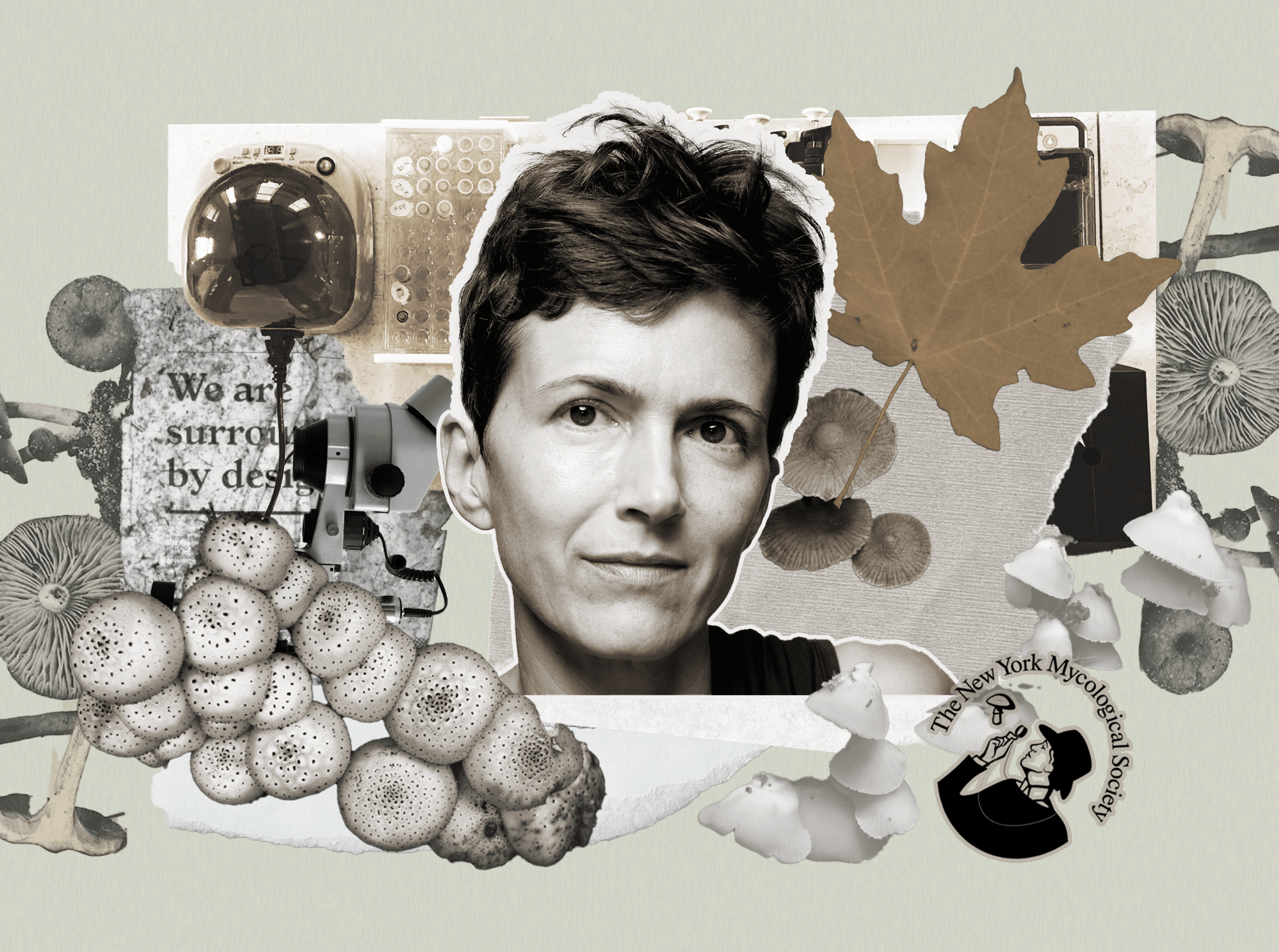

One woman’s mission to diversify and document New York City’s mushroom scene

Sigrid Jakob and other citizen mycologists are classifying fungal species before they disappear.

Avery Orrall • May 6, 2024

Sigrid Jakob surrounded by mushrooms she's documented in parks around New York City [Credit: Gayoung Lee | Elements courtesy of Sigrid Jakob]

After a long day as an independent marketing analyst, solving challenges for companies like IBM and Home Depot, Sigrid Jakob pulls out her mushrooms — not to eat, but to sequence. Her home lab, which can fit into her backpack, even has a tiny centrifuge.

Her lab represents one of her goals as president of the New York Mycological Society: taxonomy. DNA sequencing is a way to categorize species and can even help differentiate similar mushroom species from one another.

Jakob, a photographer by training, was looking for a way to “rebalance the other half of [her] brain,” a task that neither photography nor corporate strategizing could accomplish. Both are about “strategy, understanding people, developing a unique point of view, blah blah blah,” she said.

“I can’t say the same about mycology.” So what’s the overlap between photography, mycology and being an independent analyst? To Jakob, it’s about “the diligent pursuit of some kind of truth,” she responds.

Most people in the mycological club she leads aren’t mycologists by training. Bethany Beech, one of the club’s members, is a software designer who began foraging for mushrooms during the pandemic and has a knack for memorizing the Latin names of the mushrooms she finds. As she started discovering new mushrooms she couldn’t find in books, she felt the urge to classify them. That’s where Jakob came in: she lent Beech her sequencing kit and held an informal class in her living room. She even published a YouTube series during the pandemic aimed at teaching at-home foragers how to sequence their own mushroom DNA.

Citizen scientists are rising to a challenge that scientifically trained mycologists aren’t able to handle, says Roz Lowen, a former homemaker and society member who went back to school at age 50 to get her doctorate in mycology. “It’s all a matter of funding,” she says — alpha taxonomy, or the basic identification of fungi, is something institutions are no longer spending money on. Amateurs have offered a “great service” by finding, sequencing and recording fungi in databases, she says.

The world holds an estimated 2-11 million fungal species depending on who you ask, yet only roughly 150,000 of them have been classified, says Jakob. And none of them are protected by the Endangered Species Act, she says, “even though we’re losing fungi at the same rate as trees, plants and animals.”

But classifying mushrooms isn’t just about saving them: “The vast majority of trees and plants have fungal partners,” she says, “so understanding healthy ecosystems requires that we understand the role of fungi in these ecosystems.” Mushrooms are often in symbiotic relationships with other wildlife, Jakob says, so they are part of a bigger picture — one that has often been neglected.

“Fungi were considered like parasitic plants in a lot of textbooks up until the 1960s,” Beech added.

Jakob’s home lab, which she uses to sequence mushrooms [Credit: Sigrid Jakob]

Jakob’s medium of choice for finding new mushrooms: fecal matter. And yes, she knows how that sounds to the uninitiated. “Oh my God, who are these freaks who study mushrooms growing in poop, you gotta be so weird… But then I thought, ‘There’s so much beauty in all this poop,’” she says. Viewing fecal fungal growths under a microscope “is the most beautiful and relaxing thing I’ve ever done. It’s like floating, like being underwater.”

Her most recent taxonomic contribution grew from her fascination with fecal matter: she discovered deer droppings in Van Cortland Park last winter. They were covered with a black layer of what she originally thought was mold. When she realized it was fungus, she thought, “Wow, this is a mushroom that makes its own blanket. That’s pretty cool.” A forum posting introduced her to Michael Richardson, a retired Scottish mycologist, who had discovered the same fungus 20 years ago. They named it Sporormiella tela and published their findings in a recent paper.

Jakob is also a board member of the Fungal Diversity Survey, a “Noah’s Ark effort” to document thousands of fungal species. Many will be studied and sequenced with the assumption that they will go extinct: “This will be the first — and the last — record that we have of them,” she says.

While Lowen agrees that the disappearance of fungi is urgent, she attributes the scarcity of some species to how rare they are. “It’s tricky to know whether something is really becoming extinct, or whether it’s just obscure and nobody’s looking for it,” she says. Global warming is making some species hard to find, she says, but it also may be contributing to the redistribution of fungi: in areas you may have found a species before, the climate has changed enough that it’s no longer present there, but it might be present elsewhere.

The club — with a current member count of over a thousand — documents most of its taxonomic findings, including DNA sequencing and images, in data systems like GenBank and iNaturalist. Jakob says that on almost every walk, they find something they haven’t seen before. They have documented over 1,600 species in New York City.

But why New York City? For Jakob, it started with “Harriet the Spy,” a children’s book about an adventurous young girl living on the Upper East Side. She was excited to discover that even in New York, if you know where to look, nature can be both abundant and diverse. That’s especially true for fungi, mostly because there are a lot of exotic trees. “This is a city of immigrants from a plant perspective as well as a human perspective,” Jakob says. “And obviously, there’s many more eyes to the ground. People don’t want to make eye contact with each other.”

New York City is also the perfect stage for Jakob’s second club goal: member diversity. “Mycology itself has a bit of an age problem,” Beech says. “And a bit of a gender problem. It’s changing, but even up a few years ago, it was really dominated by, like, old white guys.” Intentionally or not, she says, mycology has become gatekept. “Sigrid has so consciously decided not to do that.”

“Mushrooms are a very diverse, eclectic group,” agrees Journei Bimwala, the board member responsible for community partnerships. “It just doesn’t make sense for it to be exclusive. Nature is something that belongs to everyone.” Bimwala, who Jakob brought on board a year ago, was responsible for organizing the second annual Fungus Festival on Randall’s Island in October 2023. Guests at the Fungus Festival attended events such as mushroom ale tastings and mindfulness yoga sessions inspired by fungi. She also works closely with BIPOC communities like the Bronx River Alliance to hold shared events.

Jakob’s third and final goal as president: “I really wanted to become part of a larger mycelium of organizations that care about nature.” She recalls the club’s 60-year feud with the Parks Department, including “bolting because we were worried we would get arrested” for sampling some of the fungi in New York City’s parks.

Now, she says, “We need to be partners. We have the same agenda: we’re trying to increase knowledge of the natural world and protect our environment. So we should be friends, not enemies.” While foraging for mushrooms in New York City is still technically illegal, members of the society are allowed to gather mushrooms under the guise of research. The society has research permits from the Parks Department that allow members to forage, but the club tries to keep gathering for food limited and quiet. Their website recommends not over-picking edible mushrooms, and states: “Do not ask people for their edibles spots, unless you know them well” (followed by a smiley face).

The New York Mycological Society is part of the North American Mycological Association, a network of clubs all sharing the same goal: preservation, documentation and appreciation for fungi. As Jakob says, “Mycology is for everyone. But mostly non-scientists who just care a lot, like me.”