Tracing cognition from clay stamps to cuneiform and beyond

What the formation of writing can tell us about human cognition

K.R. Callaway • March 6, 2025

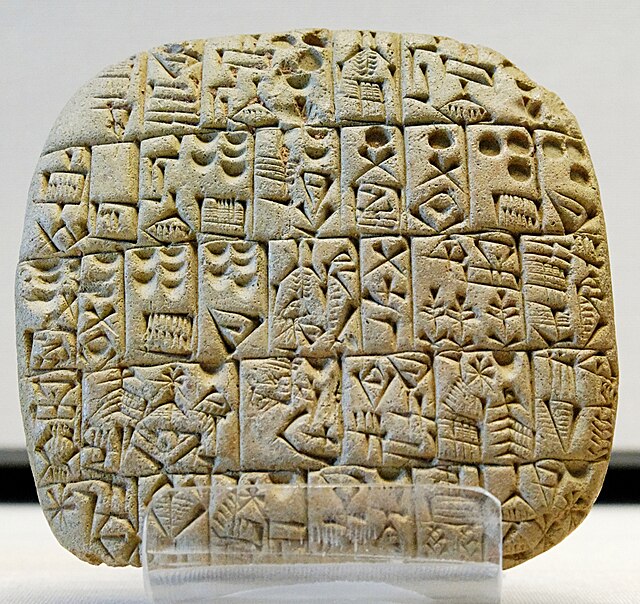

Written by pressing wedge-shaped reeds into unbaked clay, cuneiform is the earliest known writing system — but that doesn’t mean it is the first step in writing’s development. [Credit: Marie-Lan Nguyen | Public Domain]

In the fourth millennium B.C., the southern Mesopotamian city of Sumer was urbanizing — cities formed, trading posts were established and the administrative needs of cities became more complex.

Some historians believe this complexity called for a way of keeping track of administrative and economic activities — like exchanging livestock, produce, textiles and pottery — which could represent more than the small clay tokens and symbolic seals stamped into clay that were previously used to track what and how much was being traded. This is where writing came in.

“Many people say writing was probably invented [in the Sumerian city of Uruk],” said Kate Kelley, a research assistant working on the University of Bologna’s Invention of Scripts and Their Beginnings project, or INSCRIBE. “We don’t have a smoking gun, but that’s certainly where we have the earliest [script] coming from, and one of the main arguments for the invention of writing has been that it probably fit an administrative need.”

The ability to keep administrative records, track purchases and even externalize thoughts by writing them down on paper is something many of us take for granted, but writing has not been around forever. Some cognitive archeologists, those who study minds of the past by analyzing archeological artifacts, focus on the way writing systems emerged and evolved alongside both the material world and the human mind — from writing’s precursors to modern literacy.

Cuneiform, which encodes the Sumerian language and first appeared at the end of the 4th millennium B.C., is considered to be the first written language in ancient Mesopotamia. It is named for the wedge-shaped strokes that make up cuneiform’s characters, after the Latin “cuneus,” or wedge.

Cuneiform is an example of what Olivier Morin, a cognitive scientist at Institut Jean Nicod, calls “true writing.” In true writing there can be irregularities, but the system should have a set of rules that mean it can be reliably read. By reading, Morin means that one can see a sign and pronounce it correctly due to the ties between the sign and the sounds of the language encoded in the writing system.

Before there was cuneiform, there was proto-cuneiform, a system of written symbols from earlier in the 4th millennium B.C. that did not fully encode a language like true writing would, but could still communicate more complex ideas than could be conveyed by symbols stamped onto clay or clay tokens used to keep track of commodities.

The INSCRIBE project, led by University of Bologna professor Silvia Ferarra, was created to unravel some of the mysteries of how writing developed from stamps to proto-writing to true writing. Research connecting signs used in proto-cuneiform to the symbols used on cylinder seals — engraved, cylinder-shaped stones that could be rolled over clay to impress symbols or scenes on it — was recently published in the journal Antiquity by Ferrara, Kelley and Mattia Cartolano, another INSCRIBE research assistant.

“From previous studies, we know that, with regards to proto-cuneiform, there are different ideas that led to an invention of writing,” Cartolano said. “For many years, there has been so much emphasis [in research] on tokens influencing the emergence of writing. Well, what we actually found out is that tokens were just part of the process [behind writing’s emergence].”

This discovery of how symbols jumped from stamps to writing came after Kelley recognized a sign in proto-cuneiform that looks like a clay vessel with a net around it — and also looks like a symbol used on the cylinder seals she and other researchers had been studying.

“I thought, ‘This is a funny looking vessel,’ and, ‘I wonder what that is,’” Kelley said. “And it was very clear to me, quite suddenly, because Mattia and I had just been looking at a big database of all the seals, and we saw this motif occurring again and again, and this is that netted vessel.”

Being able to demonstrate the connection between the stamp and the written sign shows that other images — beyond the signs used in proto-cuneiform and symbolic physical objects like tokens — can help us understand the development of writing and the cognitive changes behind it, according to the researchers.

“Together with the first creation of images back in the paleolithic times, writing was a great leap from a cognitive perspective because it allows large communities to connect even further,” Cartolano said. “It’s a really important step in our evolution.”

Proto-cuneiform was an important step on the path to true writing. It shows a willingness and ability to create a standard system of symbols and use them to express more complex ideas about the physical and social world around them.

The leap from proto-cuneiform to cuneiform took centuries, as symbols were added and the system of writing them was refined, but the development of proto-cuneiform laid the groundwork for further evolution of writing systems in ancient Mesopotamia.

Leee Overmann, a cognitive archeologist, outlines some of the major developments that take place in this evolution — and what we can learn about cognition by observing artifacts left behind by ancient societies.

Over time, the order and appearance of strokes used to write became more standardized, which can decrease the mental effort writing itself takes and means that “you can focus on what you’re writing — the content — rather than the mechanics of producing the writing,” according to Overmann.

As writing systems develop, you also stop seeing irregularities in form — like words being split between lines of text — and messier styles of writing, such as cursive, become more common as writing speed and tolerance for ambiguity in reading increases.

Each of these developments is a step towards literacy, which Overmann said reorganizes both the brain and the material form of writing and maximizes their ability to work together smoothly.

“Writing is a system of graphic marks, but it’s been shaped under specific forces to do specific things,” Overmann said. “That’s, I think, a very important concept for understanding how writing as a material form reorganizes what literacy really is. Writing has become a tool that lets us externalize mental content, look at it, refine it and share it.”

Because early writing systems in Mesopotamia were written on long-lasting materials like clay, the region is a “really nice test case” for understanding the evolution of writing, Overmann said. However, the lessons learned about how writing developed and how these developments shaped cognition likely apply to other regions and other writing systems as well.

“The same kind of behavioral and neurological reorganizations are taking place [in the development of different writing systems],” Overmann said. “And why do we know this? [In modern] neuropsychological studies and experiments with different writing systems, different languages, different individuals and so on, it’s the same parts of the brain that are active.”