What’s the future of science during Trump’s second term?

How the Gold Standard became tarnished

Tom Brown, Leslie Liang • September 17, 2025

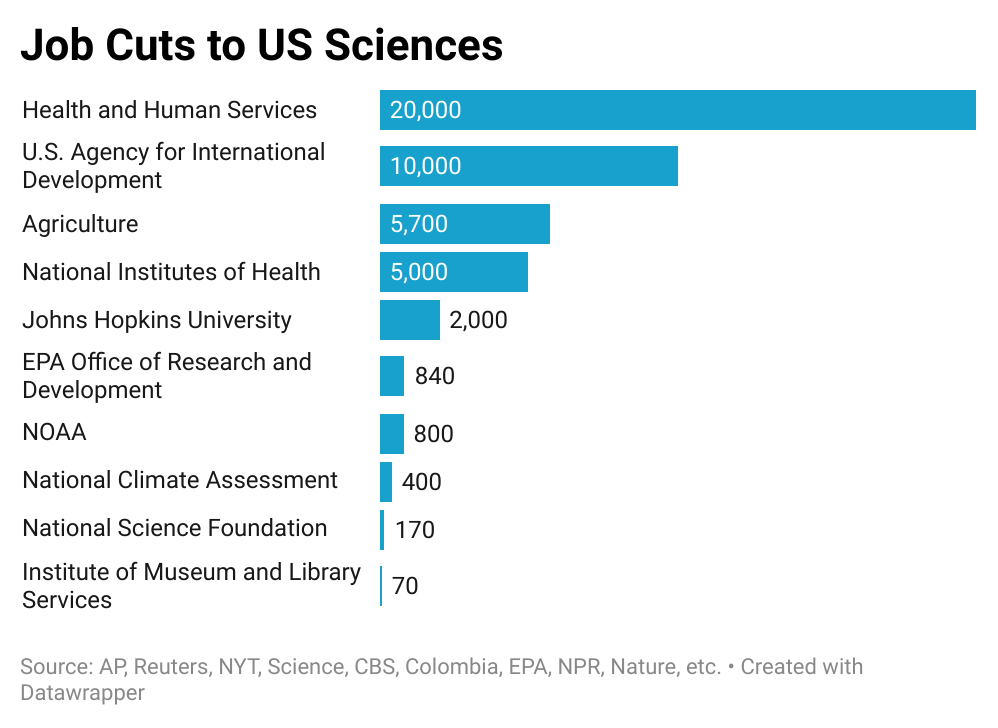

In his first eight months of office, the second Trump administration has overseen the firing or buyout of more than a quarter-million employees, and cut out at least $36 billion in science funding, according to a dataset compiled by Scienceline. The science funding deficit is set to reach $163 billion by 2026, with institutions ranging from the Weather Service to the National Parks seeing their funding cut. Researchers, citizen scientists, and science communicators across the US are now having to adapt to an industry in upheaval.

“We have seen an all out assault on American science,” says Gretchen Goldman, an environmental engineer and president of the Union for Concerned Scientists, who previously served in the Department of Transportation and the White House. “It will harm people across the country and the world.”

On May 23, the Trump administration released a statement titled Restoring Gold Standard Science, which said that “confidence that scientists act in the best interests of the public has fallen significantly,” and that a majority of researchers believe science is facing a reproducibility crisis, a reference to the concern that a growing number of scientific research cannot be repeated to test its validity.

It’s true that confidence in science among the U.S. public has plummeted over the past decade. In 2023, confidence levels sank to the lowest seen since 1972, with only 23% of Americans stating they had a great deal of confidence in science. Levels had fallen 14 points since the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I think COVID made things a lot worse, because it increased distrust and really exposed how difficult it is to communicate uncertainty to the public,” says Jennifer Kates, senior vice president and director of the Global Health & HIV Policy Program at KFF, a health policy organization in the U.S. “I think a lot of what is true in science and medicine and health is uncertainty.”

The administration’s claims on reproducibility are supported by Nature’s 2016 survey of 1,500 researchers, which found that over 70% of respondents could not reproduce another scientist’s experiment. However, the same survey found that less than 31% thought that failure to reproduce published results meant that the result was wrong.

The majority of scientists in the survey said it was easier to get funding for new studies than for replicating old studies, creating a perverse incentive for researchers to move on. Many studies are also not replicable because they use anonymous participants, so researchers aren’t able to reproduce the study without breaching privacy laws.

Brian Nosek, professor of psychology at the University of Virginia, said in a post on Bluesky that this “weaponization of the reform movement” is becoming a “justification for reducing investment in research,” and a means of throwing out science which doesn’t align with White House objectives. “This is a logical error, like saying the faucet is leaking so the house should be burned down,” Nosek added.

Dominique Brossard, a professor of science and risk communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says that the Trump administration’s funding cuts should not have come as a great shock. “Since Trump’s first term, he’s had four years to plan this,” she says. “So all those executive orders came, most likely, from a concerted effort.”

Secret Science

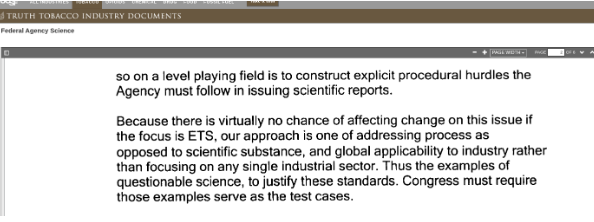

When Trump was first elected, reporters from The New York Times traced the Republican transparency directive that informed the new “Gold Standard” to lobbyists in the 1990s using documents from an archive created by the University of California, San Francisco library as a result of a nation-wide settlement with tobacco companies. The archive includes a 1996 memo from law firm Bracewell & Patterson stating that “concerned members are searching for a new mechanism to control EPA [the Environmental Protection Agency] and other regulatory bodies,” suggests setting up “explicit procedural hurdles the Agency must follow,” and mentions examples of “questionable science” to “justify these standards.” The author of the memo, Chris Horner, joined Trump’s transition team which oversaw the EPA during his first administration. Horner did not respond to a request for comment.

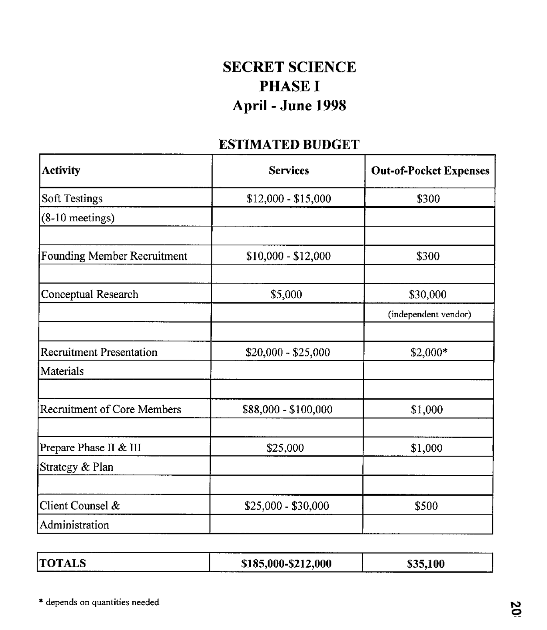

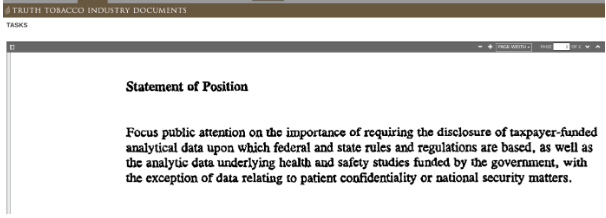

Two years after that memo, Powell Tate, a public policy, communications and lobby firm based in Washington, DC, developed a public relations strategy to insist on “the disclosure of taxpayer-funded analytical data” underpinning federal and state regulations, in order to exclude certain studies from becoming public policy. The so-called “Secret Science” project had a budget of between $185,000 to $200,000 for its initial phase. The public relations campaign to insist on transparency would eventually morph into an EPA policy of excluding studies that withhold data, including important health research containing personal information which can’t be legally shared.

The Times traced the lobbying mission to a bill that appeared in the Republican-controlled House in 2014, titled the “Secret Science Reform Act,” which died in the Senate (it was later rebranded as the Honest and Open New EPA Science Treatment Act of 2017, or the HONEST Act). Former Rep. Lamar Smith, who has received $61,050 to date from oil and gas companies according to OpenSecrets, introduced the bill.

Smith went on to work with 2017 EPA director Scott Pruitt, who embedded the legislation into regulation during the first Trump administration, according to the New York Times. In 2018, Pruitt signed the “Strengthening Transparency in Regulatory Science,” rule at the EPA, which stipulated that new regulations could only rely on research where the raw data had been made available to the general public. The results restricted the EPA from tracking how chemicals and pollutants affect public health, according to Doug Dockery, a professor of environmental epidemiology at Harvard University, as quoted in The New Yorker.

Another figure closely tied to the implementation of the Secret Science directive into EPA policy is Steve Milloy, who told the New Yorker “I’ve been working on this for 20 years,” at the time the EPA regulations on transparency passed. Milloy is a former tobacco lobbyist and regular speaker at the Heritage Foundation, the think tank behind Project 2025 which served as a blueprint for the new administration’s defunding of Federal Institutions, who also joined the same Trump transition team as Horner.

Neither Smith, Milloy, nor nor any of their respective law firms, responded to a request for comment. Pruitt could not be reached for comment.

Trump 2.0

From the point of view of several researchers who spoke to Scienceline, defunding science has become an end unto itself for the White House, which did not respond to a request for comment. “Science tends to lead to the desire to have more regulation,” said Michael Gerrard, a professor of climate change law and energy regulation at Columbia University who has practiced environmental law in New York since 1979. “And many people on the right dislike regulation.”

“The closest to this [level of cuts to Federal programs] was the first years of the Reagan administration,” Gerrard added. “This is worse than that.”

Goldman, president of the Union for Concerned Scientists, says the new administration has set about dismantling the scientific work of the Biden and Obama administrations piece-by-piece.

“It’s devastating, they are undoing everything I did the last four years in the government,” she says. “Almost everyone I worked with is now gone. … They were either forced out, or they chose to leave, or they’re not able to do that work anymore, and it’s heartbreaking.”

Much of the cuts were done under the recommendation of the Department of Government Efficiency, established by the now-departed Elon Musk. DOGE specifically requested funding cuts to the National Institute of Health (NIH), for example, according to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. Although recent polls from PEW Research show that many US citizens still support scientific research, Republican representatives have done little to push back against the White House’s Federal funding cuts.

“Republican office holders are either personally very loyal to Trump, or they are afraid of what he’ll do if they oppose him,” said Gerrard. “A couple of members have threatened to oppose him, and he then will threaten to put up candidates to run against them in the next election, for example.”

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS, lost more than 20,500 workers as of August 16, according to publicly available data compiled by ProPublica. But while the HHS is still standing, other entities, like the National Climate Assessment, have been completely hollowed out, with large numbers of staff fired and its reports edited or pulled from government websites.

“Science provides a good line item to cut for them [the White House], because they don’t concern themselves with what the value is,” said Goldman.

The NIH and the United States Agency for International Development have borne the brunt of the attacks, according to publicly reported data compiled by Scienceline. Additionally, most of the $738 billion set aside in the Inflation Reduction Act, or the “Green Bill,” passed by the former administration that was set to reshape the American energy industry, has been largely clawed back or cancelled, rolling back the largest investment to combat climate change in US history. As a result, the death toll from natural disasters such as wildfires and hurricanes, which rely on emergency responders coordinating closely with the scientific community, could be higher in years to come, Goldman said.

“This hurricane season, we’re going to see whether those cuts have any impact, either on the [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] side in terms of forecasting threats and storms and communication of that to people,” Goldman said. “And on the flip side, in terms of cuts of [Federal Emergency Management Agency] and whether people get what they’re owed in terms of recovery and help on the back end.”

On top of the cuts already pulled off in 2025, the current administration has a long list of federal programs planned for 2026’s chopping block.

Looking Ahead

Countries have started their own scientific programs aimed at luring away U.S. scientists, but it’s unclear how many are taking up the offer. The European Union has put up the most, pledging €500 million ($562 million) over three years to snap up American scientists left out in the cold by the Trump administration. The Canada Leads Program offers C$30 million ($22 million) for 100 early-career biomedical researchers, while Australia has set aside relocation packages as part of its Global Talent Attraction scheme.

U.S.-based scientists are having to adjust to a new reality of smaller funding pools and fewer applications from international scientists. International students in the U.S. studying for PhDs are particularly hard-hit, with many opting to self-censor their own academic work, according to Daniel Kammen, a professor of energy at the University of California, Berkeley, who pointed to other instances of scientists stripping out references to DEI or climate change to keep funding appearing in news reports. “All of this appears to be a process that is about something incredibly sad, and that is making already very rich people richer at the expense of their own children,” said Kammen, referring to the knock-on effect on global research climate.

“It’s now a future where we’re going to be leaner than we have had to be in our science and the projects we choose, in the kinds of work we do, in the amount of risk that we accept in science,” said Goldman, of the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). “We’re not going to have the same ability to do big things the way that we have.”

Not all scientists are suffering in silence, however. In March, hundreds of NIH employees signed the Bethesda Declaration, a letter condemning the politicization and cutback of biomedical research in the US, and the EPA issued a declaration of dissent in June. Goldman and others have decided to take the fight to the current administration directly. The UCS is suing the White House, along with the Environmental Defense Fund, after the Trump administration rescinded the scientific finding that greenhouse gas emissions endanger human health

“We can’t control politics or Donald Trump, but we can control our own institutions, and I do think it’s really important at this moment for national leaders,” said Roger Pielke Jr, a conservative think-tank fellow and climate science policy writer. “Science exists to serve all Americans, no matter who they vote for, no matter where they live, no matter what they look like, [or] how wealthy they are.”