Nobel Prize in economics honors three researchers cracking the code for sustained growth

Their work highlights the threats posed by market dominance by a few companies, restrictions on academic freedom and market conservatism

Nhung Nguyen • October 14, 2025

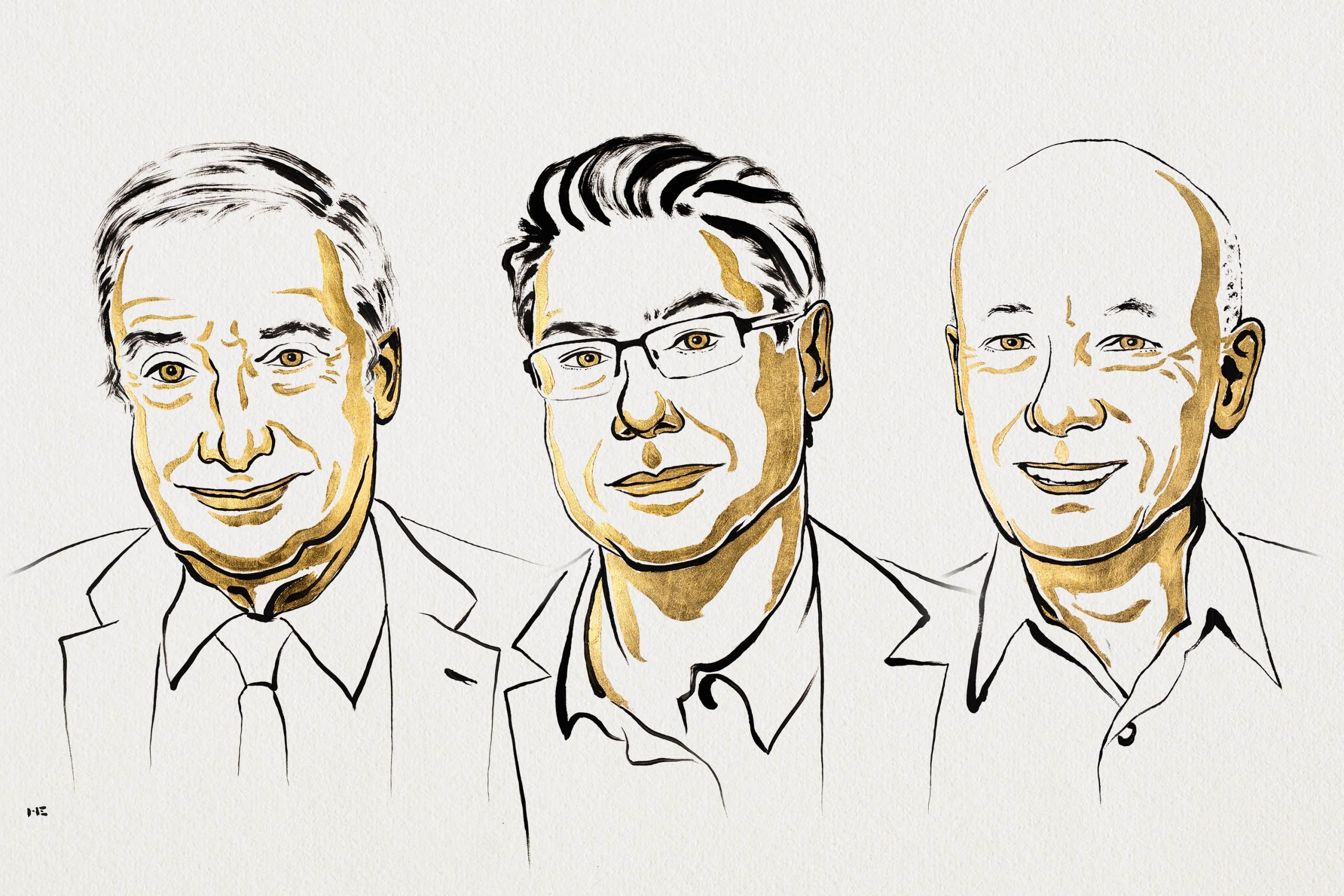

Economic historian Joel Mokyr was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics on Monday, along with two economists Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt. [Credit: Niklas Elmehed | © Nobel Prize Outreach]

Researchers Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt were awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics on Monday for identifying the essential elements of sustained economic growth.

Mokyr’s work pinpointed conditions needed to sustain growth through technological progress, while Aghion and Howitt put forth the theory of economic progress through creative destruction.

Together, they explained the continuous growth seen over the last 200 years — an unprecedented phenomenon in recorded human history. “We tend to think of economic growth as something that some people take for granted, at least in the developed world,” said Kerstin Enflo, professor of economic history at Lund University and a member of the economic sciences committee. “But it’s actually quite amazing that growth can be so sustained over such a long run.”

Throughout human history, stagnation was the norm, the committee noted. While important discoveries sometimes led to improved living conditions and higher incomes, growth always plateaued eventually.

The winners used different but complementary methods of historical observations and mathematical modelling of modern data to explain how science based innovations have turned continuous growth into “a new normal” since the early 19th century.

Mokyr identified that the mechanisms fueling scientific breakthroughs and practical applications enhance one another, creating a self-generating process that fuels sustained economic growth.

The 79-year-old economic historian from Northwestern University highlights the vital conditions for innovations to flourish within societies: openness to change and a continual flow of useful knowledge. The latter could only be established by a strong connection between propositional knowledge — knowing what is true – and prescriptive knowledge – knowing what to do with it — to turn ideas into commercial products.

“Without these, even the most brilliant ideas will remain on the drawing board, such as Leonardo da Vinci’s helicopter designs,” the committee’s press release wrote.

Meanwhile, Philippe Aghion, 69, from the Collège de France and the London School of Economics, and Peter Howitt, 79, from Brown University, used modern data to answer the same question — what makes this economic phase different from the past.

In 1992, they developed and published a mathematical economic model of creative destruction, a transformative process where new inventions out-compete and replace old ones, and push products, companies and jobs into obsolescence.

“Over time, this process has fundamentally changed our societies over the span of one or two centuries, almost everything has changed,” the committee said.

Mokyr was awarded half of the 11 million Swedish kronor (USD $1.2 million), while the rest is shared between Aghion and Howitt. The winners also receive an 18-carat gold medal and a diploma.

The economics prize, first awarded in 1969, is not technically considered a Nobel Prize. It was established through a donation by Sweden’s central bank and is not among the original five named in the will of Alfred Nobel.

The Nobel committee noted the laureates’ findings can inform current and future societies on how to balance innovation and major global challenges, namely AI, climate change and increasing inequality.

“Sustained growth is not synonymous with sustainable growth,” they wrote. While the side effects of innovations can encourage more solutions, well-designed policies are still essential for long-term development.

The committee also flagged how concentrated market power among a few firms, restrictions on academic freedom, the fragmentation of knowledge across regions, and push-back from left-behind groups can hinder it. “The laureates have taught us that sustained growth cannot be taken for granted,” they wrote in the press release. “If we fail to respond to these threats … we would once again need to become accustomed to stagnation.”

2 Comments

Awesome! Its genuinely remarkable post, I have got much clear idea regarding from this post

I found it super interesting how the Nobel Prize highlighted the importance of sustained economic growth! It reminds me of how I’ve struggled with that in my own projects. Balancing innovation while keeping proof-of-concept sustainable is a real challenge! Have you thought about how these insights might apply to tech startups?