Jupiter: Earth’s bodyguard or secret assassin?

The gas giant’s mighty gravitational pull slings comets and asteroids towards Earth, while also deflecting them away

Naveena Sadasivam • November 29, 2012

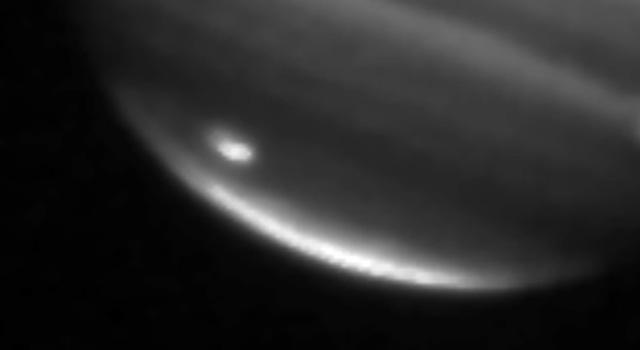

A 2009 collision into Jupiter was captured by NASA’s infrared telescope in Hawaii. [Image credit: NASA/JPL/Infrared Telescope Facility]

When George Hall, an amateur astronomer in Dallas, went to bed on September 9, 2012, he didn’t know that the telescope he had left trained on Jupiter would, in the wee hours of the morning, capture the telltale signs of an interstellar object crashing onto the planet’s gassy surface.

After he released the video on his website and news of it spread, some journalists proclaimed that Jupiter had taken another bullet for the Earth, ensuring our planet’s habitability. But Jupiter’s flirtations with comets and asteroids have never been consistent; at times it has sucked them into a planetary embrace and other times has slung them away toward Earth. Some astronomers believe it may cause as much havoc as it prevents for Earth and its neighbors.

Jupiter is a cosmic colossus. With a gravitational field more than double that of the Earth, it has the power to swirl around looping asteroids and comets. Cosmologists estimate that large asteroids — ones with diameters over one kilometer — hit the Jovian atmosphere every couple centuries. Fortunately, such collisions are significantly rarer on Earth: just every 500,000 years or so.

Hall’s recent observation was much smaller than the massive asteroid that probably caused the extinction of dinosaurs. At about five kilometers in diameter — just under the length of 55 football fields — its combusting flash on Jupiter barely lasted two seconds.* As far as interstellar flyby attacks go, this scale of collision is quite common.

Since 2009, astronomers have spotted four such collisions on Jupiter. The most well known is the 1994 collision by the comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, which spectacularly broke into 21 pieces over a period of six days and rained down on the Jovian atmosphere.

These prior instances seem to bolster the case that Jupiter is our guardian angel, right? Not so, say some astronomers. It is true that the planet exerts a tremendous gravitational pull on objects passing by, but its effects can either be troublesome or favorable. By altering the path of passing comets, it sometimes draws them into itself. But at other times, Jupiter’s gravity fails, and the comet is booted off towards the inner solar system — and us.

“There have been recent simulations showing that Jupiter’s constant meddling with the asteroid belt sends rocks into the inner solar system,” said Timothy Dowling, an atmospheric physicist at the University of Louisville.

One such simulation was published by astronomers Barrie Jones and Jonti Horner, astronomy professors at the Open University and University of New South Wales respectively, but their inferences do not support Dowling’s premise. They studied how the impact rate on Earth would change if Jupiter were smaller, and discovered that there would be little change on Earth even if Jupiter were removed entirely from the solar system.

But Harold Levison, a planetary scientist who studies the dynamics of astronomical objects at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado is wary of their study. Any simulation would be unreliable, he said, because there are way too many factors to take into consideration. “We could never build the solar system,” he said. Dowling agrees: Whether Jupiter plays a crucial role in ensuring Earth’s habitability “is just not known,” he said.

With such conflicting theories, the topic remains shrouded in controversy, and astronomers are divided about whether Jupiter’s presence helps protect us or places us in the path of destruction. But the fact remains that Jupiter continues to get pelted by passing objects; whether these objects were at some point headed towards the Earth is not yet conclusively known.

*Correction, December 1, 2012:

Originally, this article read that the meteor which struck Jupiter was five kilometers in diameter, or the length of 10 football fields. This is inaccurate. Five kilometers is closer to the length of 55 football fields.

1 Comment

In 1998 Jupiter saved with its massive gravitational pull you could see the meteor in earth’s atmosphere but then Jupiter took it in the last second and took the hit but go back about hundreds of millions years ago the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs and 2/3of the earths life form I and Jupiter was there so I think 2 theories

#1 Jupiter’s gravity will go down every hundred million years letting meteors to enter earth surface. #2 some meteors have unknown u objects in them that will act like magnets to burning hot stuff or other metals like gold and iron. If it is even one is true it is to be took very seriously here’s why. if this is one of those hundred million earth could very well be over. 2 if its burning hot stuff it should be attracted to Venus and the sun both being pretty close to earth and what if meteors come from different galaxies I know why isn’t a black holes gravity over 100’00’00 the suns so Phoenix A gaia BH1 and cyguns_X1 so those black holes could be pulling meteors from other galaxies Witch is a massive terror if its true because if there pulling stuff from galaxies if its true our solar system is just a ticking time bomb