Nature on the edge

Rock climbing’s increasing popularity puts pressures on cliff landscapes

Michael Koziol • August 29, 2016

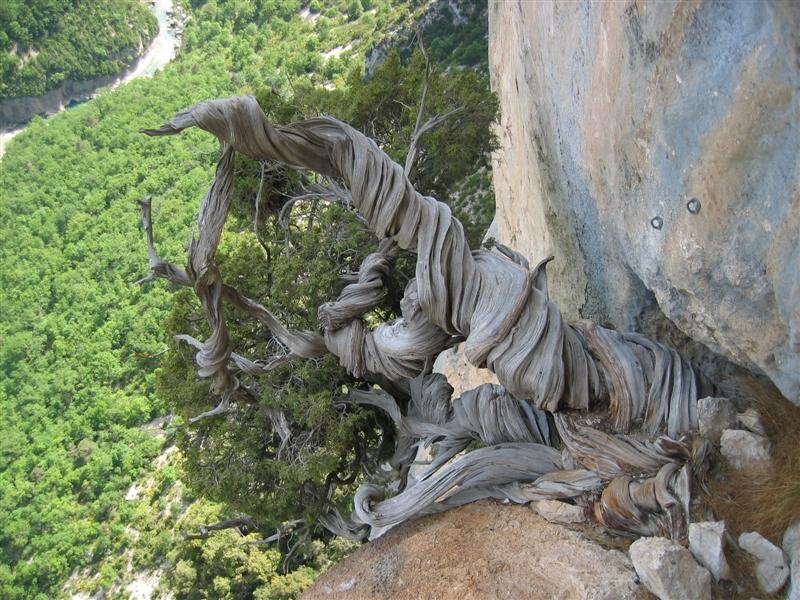

Ancient trees clinging to a cliff’s edge in the Verdon Gorge, France — an area with a long history of climbing — have survived centuries of storms and erosion, but rock climbers are an even bigger challenge. [Image credit: Doug Larson and Jean-Paul Mandin]

Four years ago, in a nature preserve in Ardeche in southern France, a group of rock climbers stumbled on an exciting new cliff to scale. There were just two problems: Climbing was prohibited outside of authorized routes, and this new route was blocked by an ancient Phoenician juniper. But the climbers couldn’t resist, so they cut down the tree and cleared the route. Later, a local researcher examined the fallen trunk and was startled to count at least 1,260 rings: The juniper had been growing there since the eighth-century, until it had the bad luck to encounter such avid climbers.

“They were blinded by their own climbing passion,” says the retired biologist Jean-Paul Mandin, who counted the rings. Mandin is the current president of the local botanical society, the Société botanique de l’Ardèche. He’s quick to note that most climbers are careful not to disturb the vegetation, but when climbers want to establish a new route, their efforts take a heavy toll on the cliff. “The climbers rope down the cliff, fix the bolts for security, bring down unstable stones, and brush the stone to remove lichens and mosses,” Mandin says.

Animals that make the cliffs their home are also affected. Biologist Doug Larson, now retired, found that climbers often look for the same qualities in cliffs as its indigenous residents. “Those golden nugget areas where little pockets of dirt gather,” says Larson, are “precisely the areas climbers favor.” So many climbers will clear out those dirt pockets, disturbing the plants and animals already there.

Damage can even be done to the rock itself. Ten years ago, Dean Potter climbed Delicate Arch, a beloved Utahan landmark, at Arches National Monument. His climb strengthened the Park Service’s regulations, banning any future climbing on the arches, after Potter’s rope wore grooves into the rock. More recently, climbers Joe Kinder and Ethan Pringle caught flak from the climbing community for removing two trees in Tahoe, California to clear a new route. And around the country, climbing routes are routinely shut down to protect nesting peregrine falcons, adding to the list of clashes between climbers and the cliffs they scale.

“Climbers are in an area years before scientists decide to go study it,” says climber Peter Clark, who founded Cliff Ecology Environmental Consultants in 2009 and assists both private landowners and parks officials to develop plans for managing cliffs. “In a lot of ways, we don’t know how it was before it was impacted by early climbers.” But to the knowledgeable eye, the effects are there. “As a climber, there are definitely large, measureable impacts at most climbing areas.”

The growing interest in climbing worsens these impacts. Climbers are choking out popular sites such as the Roadside Crag in Kentucky, which prompted the landowners to close it down. At Roadside, the owners found severely eroded areas continuing to be climbed and damaged, as well as large groups of people waiting for routes to open up and destroying the area around the cliff in the process. Crowded sites are becoming the norm as the sport grows, both on the rock and in the gym. In 2015, there were 388 commercial gyms in the U.S., compared to only a handful in the 1980s.

In the wake of climbing’s tremendous growth, climbers, advocacy groups and landowners need to know how to handle the potential impacts. “That’s the million dollar question, that’s what everyone wants to know,” says Clark. “I don’t think there’s a silver bullet solution.”

The first studies on the effects of climbing on cliff ecosystems weren’t conducted until the 1990s, when park managers first began imposing access rules on a sport that had been largely unregulated before then, according to Mike Farris, a professor of biology and environmental studies at Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

At around the same time, Larson was studying the lichens and trees clinging to cliff faces in the Niagara Escarpment, a geologic formation that stretches from New York to Wisconsin along the Great Lakes. During his research, he noticed that he was often working in the same areas climbers were frequenting. He realized those climbers could be useful in accessing difficult-to-reach areas and helping in his research.

Larson’s studies and others gave park managers reasons to reconsider open access policies to climbing locations. Climbers responded, too. In 1991 they formed the Access Fund, a nonprofit advocacy group that focused on maintaining access to already established climbing regions. In more recent years the organization’s focus has shifted more to preservation, according to Zachary Lesch-Huie, who works with local grassroots climbing groups as the fund’s national affiliate director. He says the Access Fund’s mission is to protect climbing environments, which is broader than just ensuring access. The greater need, Lesch-Huie says, is to sustain cliff ecosystems for future generations.

The Access Fund’s Rock Project seeks to build environmental awareness in climbers starting with their very first experience, which often begins in climbing gyms. The project offers “a healthy indoctrination into the climbing ethic” by emphasizing stewardship work like picking up trash or proper trail building, Lesch-Huie says. While the worst damage comes from reckless climbers, the regular process of climbing will naturally cause some wear and tear on the cliff. The key, he adds, is to reach climbers before they’re on cliffs, because first-time climbers can do a lot of damage.

One common concern is protecting peregrine falcon nesting sites. It’s common for climbers to be the ones to report a new nest to park officials, according to Lesch-Huie. Due to widespread usage of DDT as a pesticide, the number of nesting pairs plummeted to only 324 in 1975, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Now, due in small part to climbing closures during their nesting season, there are an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 nesting pairs.

The sport’s growth means that there will always be pressure to establish new routes — to climb where no one has climbed before. “That’s always been core to the climbing,” Lesch-Huie says. But he thinks the effects of such trailblazing can be eased by educating climbers on standard trail building practices, providing low-impact usage from the very beginning.

Education can only go so far, however. Back in Ardeche, even after concern over the destruction of the ancient juniper, two more trees — each more than a century old — were chopped down in the preserve last December, not far from the famous Chauvet Cave, which has some of the world’s oldest cave paintings.

Farris says his concern is not with veteran climbers, who have good technique and will impact the cliff less. He’s worried about the less experienced climbers eager to find their own route, using power washers and crowbars to clear a path through these pristine regions. “These folks are under pressure to produce new routes,” Farris says, “leading to the potential of establishing routes where they simply shouldn’t exist.”