Trump’s budget cuts threaten national parks, wildlife refuges and the science behind them

The loss of senior officials, scientists and other specialists might lead to the loss of institutional knowledge that’s been built up and maintained for years

Gaea Cabico, Miriam Bahagijo • September 17, 2025

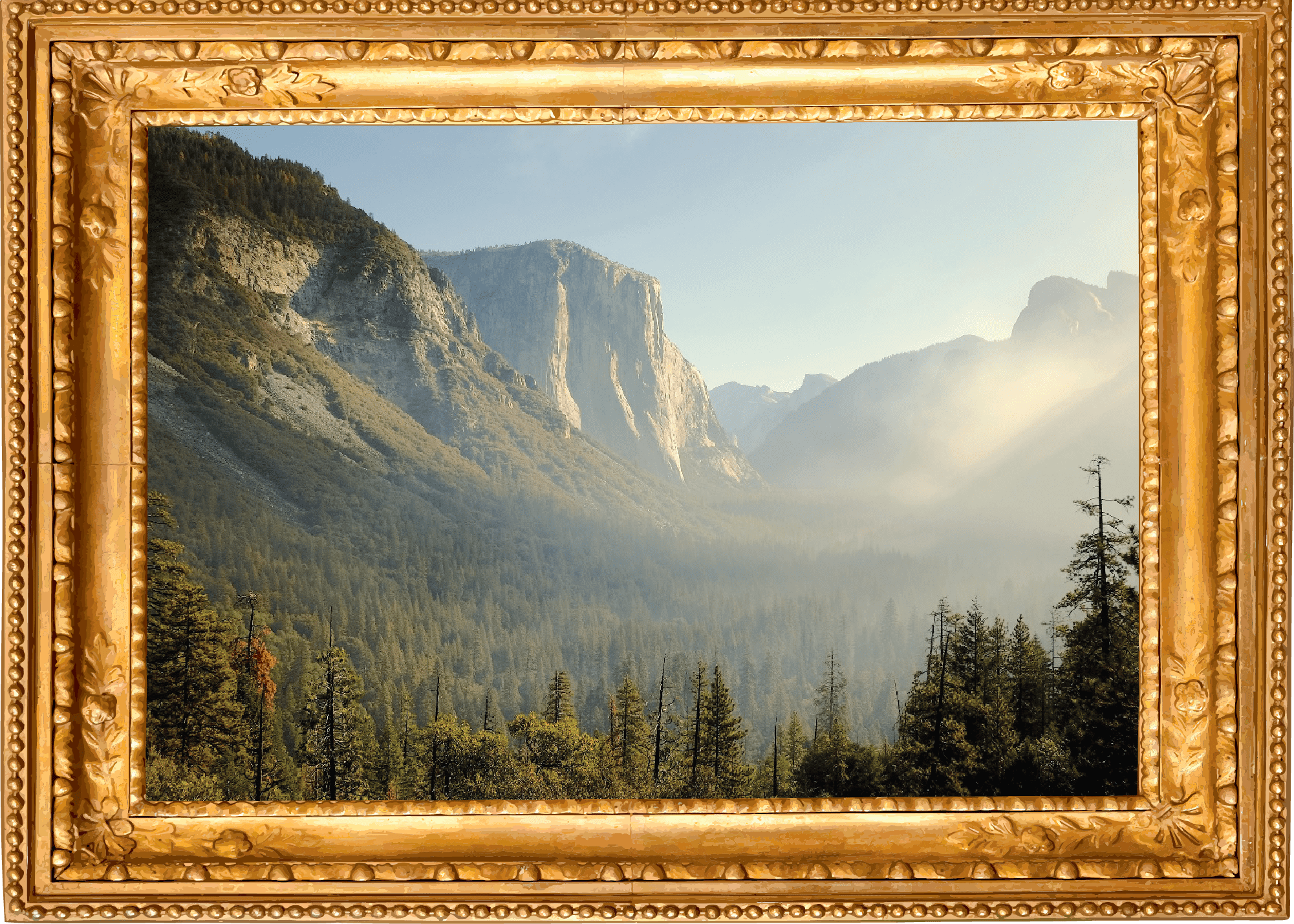

Yosemite Valley within the Yosemite National Park, where Sue Fritzke had worked as a seasonal park guide during her time with the NPS [ Image credit: Aan Kasman | Unsplash] [Frame credit: Daniel | Adobe Stock Education License]

The National Park Service was once a dream workplace for Sue Fritzke. Over her 38-year career, she worked in some of the most iconic American landscapes — Yosemite as a seasonal park guide and Capitol Reef as a superintendent — as well as quieter and often overlooked sites like Muir Woods National Monument and Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park in California.

“I had grown up in California, visiting places like Yosemite National Park, Point Reyes National Seashore, and had gone to Muir Woods as a kid,” Fritzke told Scienceline. “I just really sort of developed a love for that whole concept [of national parks].”

Fritzke retired in 2023. But now she is watching from the sidelines as the National Park Service, or NPS, faces steep budget cuts that threaten the operations of 433 park units — including not just the 63 national parks, but hundreds of smaller, lesser-known sites like national seashores, monuments, and historical parks.

This assault on the agency she devoted her life to has influenced a major decision: Fritzke is now packing up her life in the U.S. and moving to Canada.

“I feel like it’s under attack, and it’s a heartbreaking thing to be watching the demolition of so much of what I actually worked on over the years,” said Fritzke, who is also a member of the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks. The organization, made up of 4,600 former, current, and retired NPS employees, advocates for the protection of the United States’ most precious natural and cultural resources.

What’s at stake is not just visitor experience, but the scientific foundation of public lands in the country. Forest rangers, biologists and other specialists who monitored ecosystems and protected vulnerable species were forced out, affecting projects and programs that informed how parks and refuges were managed, advocates and scientists told Scienceline.

Crippling budget cuts

The National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), an independent organization that works to protect and enhance the park system, reported the NPS has lost 24% of its permanent staff since President Donald Trump took office in January 2025, leaving parks across the country scrambling to operate with skeleton crews.

Moreover, the budget reconciliation bill also rescinded $267 million previously committed for national park staffing. This has left many units of the park system short-staffed, as it led to firings, delayed hiring, and a wave of early retirements.

According to NPCS, an estimated 2,400-2,500 National Park Service employees were “forced” to resign or retire under the “Fork in the Road” offer, which allowed them to resign now but remain on the payroll through the end of the fiscal year, or take an early retirement buyout.

“I think the other real serious problem for the park service is that many of those 2,500 or so staff who took the buyouts were in positions like archaeologists, historians, biologists, engineers, as well as scientists, who were doing a lot of projects ranging from data gathering and resource monitoring, and they are going to come to a halt” said Bill Wade, executive director of the Association of National Park Rangers (ANPR).

Many of those projects supported smaller park units that lack the resources to conduct their own research. “So they have to rely on the expertise from the central offices, and now a lot of that’s not gonna be there, so that’s really going to affect how the management of the smaller areas is undertaken,” Wade said.

He also noted that many of those forced to resign were senior leaders, which means the Park Service is going to be managed by “people who are less experienced.” In other words, the parks risk losing expertise, experience, and institutional knowledge that has been accumulated over many years during the parks’ operations from these forced buyouts.

Citing a Park Service report from last July, the NPCA said that around 90 national parks experienced problems tied to staff departures, funding cuts, and hiring delays in recent months. At Acadia National Park in Maine, for instance, staffing vacancies led to the closure of entrance booths, resulting in longer lines at the gate and shortened operating hours. The park also cancelled its program that gives teens hands-on work experience in Acadia because of staff shortages.

“Parks are cutting hours, closing visitor centers and struggling to respond to emergencies simply because there aren’t enough staff,” said Theresa Pierno, president and CEO of the NPCA, in a press release. “Losing a quarter of the Park Service’s permanent workforce has made it nearly impossible for some parks to operate safely or effectively. And sadly, this is just the beginning.”

While funding cuts at big-name national parks like Yosemite, Yellowstone and Grand Canyon often get a lot of attention, lesser-known park units are feeling the squeeze just as much—if not more. According to the NPS report, staff shortages at Cumberland Island National Seashore in Georgia left the fire team with only one member, ceased trail maintenance by NPS staff and limited visitor services with no rangers to greet visitors taking ferries. Meanwhile, at Gateway National Recreation Area in New Jersey and New York, hiring and contract delays reduced lifeguard-protected areas.

What’s at risk

It’s not just the National Park Service. Budget cuts have also impacted the US Forest Service, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Bureau of Land Management. Collectively, these four groups manage around 95% of the 640 million acres of federal land in the United States.

In February, for example, the administration terminated around 420 employees in the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) who were newly hired or recently promoted, which accounts for 5% of the agency’s workforce. Both the NPS and FWS are overseen by the Department of the Interior, and both often collaborate closely on conservation efforts.

Desirée Sorenson-Groves, president and CEO of the National Wildlife Refuge Association, shared the same concern as Wade regarding the forced buyouts, as many scientists who left the FWS felt “they were forced out because of the issues they work on.”

The FWS oversees, among others, the National Wildlife Refuge Systems, migratory birds, as well as endangered species under the Ecological Services, and Groves said science itself is under attack in many different ways, from funding cuts — which reflects the abysmal commitment to protect federal lands and opening them up for extraction instead — to the reduced protection status of endangered species.

At least for the FWS, what it all comes down to is that we might lose the will of the American people to protect wildlife species. “You protect what you value, and if you don’t even know that something exists, you won’t value it,” said Groves.

Potential handover to states

The Trump administration also proposed to transfer smaller, lesser-visited parks from federal management to states and tribal governments. Most NPS units were established by acts of Congress, and transferring them to states would require new legislation, Sen. Martin Heinrich, a Democrat from New Mexico, said in a release.

Wade found it hard to believe that state and local entities would be willing to take them over, given that many of these park units are already in poor condition, and would require a lot of effort to restore. States and tribal governments also often lack the funding and resources that the federal government provides to manage and maintain national park units.

For Fritzke, the significance of these public lands and protected areas is not merely their natural beauty, but their ability to tell the nation’s history — whether it’s the big and famous national parks like Yellowstone, or even the less visited ones like John Muir.

“That is really the role of the national park system: to tell these stories,” Fritzke said. “Whether they are a story that reflects well on us or a story that maybe is difficult for people to acknowledge.”

1 Comment

We have to stand up!!! Are there organizations working to come together on this?? We CANT LOSE THIS LAND!!!!!