What can a coral-inspired pill teach us about the gut microbiome?

A new capsule measuring the small intestine’s microbes may help better illuminate the mysteries of the gut microbiome

Georgia Michelman • January 23, 2026

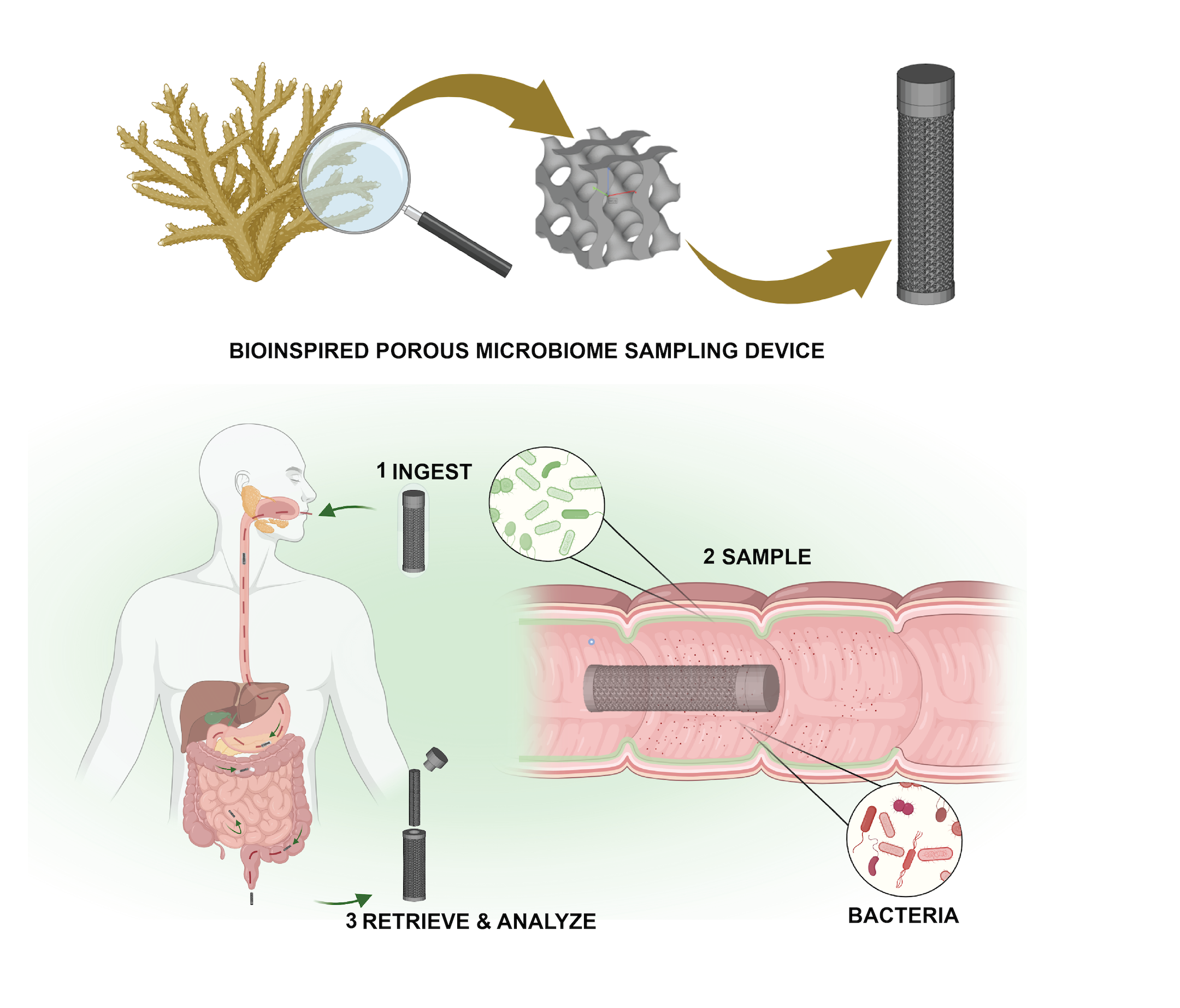

The capsule, which is based on the structure of coral, collects bacteria from the small intestine, whose microbiome has been historically difficult to study. [Credit: Hanan Mohammed | NYU Abu Dhabi]

The health-conscious pockets of the internet won’t shut up about the gut microbiome. But despite a commercial explosion of “gut-positive” drinks, pills and seed varieties, research on the value of these interventions lags behind.

One limitation of gut microbiome research is its reliance on stool samples, which mainly reflect the large intestine’s bacteria. At five feet long, the large intestine only represents the final fifth of the gastrointestinal tract. Despite being an important center of gut action, the small intestine is much more difficult to sample from, so its microbiome has been long left out of research.

A new tool could change that. A study, published in Device, describes the design for a new capsule — inspired by the mathematical structure of coral — that can collect bacteria from the small intestine.

The scientists found that the capsule, when used in rats, collected a much more representative sample of microbes from the small intestine than stool did. They are moving onto trials in humans early this year, in collaboration with NYU Langone Health.

“Every couple of centimeters [of the gut] has different microenvironments,” said Hanan Mohammed, a postdoctoral associate at NYU Abu Dhabi who led on the paper. “To take the lower part and say, ‘hey, that’s a proxy for the entire seven meters’ is inaccurate.”

In order to explore the microbiome of the small intestine, Mohammed’s team had to get creative.

To design their capsule, which they cleverly named CORAL (Cellularly Organized Repeating Lattice), they looked to mathematics, homing in on the structure of coral, whose spongy anatomy is home to a variety of marine microbes. These structures have a maze-like interior, and are hollow and strong. Additionally, they are easy to 3D print, the method used to create the capsule.

As the capsule passed through the small intestine, Mohammed and her team theorized, the structure would naturally trap bacteria in its inner labyrinth — no moving parts or batteries required.

The researchers first used computer simulations to experiment with the capsule’s design.

The rats’ gut liquid needed to flow into the capsules at just the right rate, sampling bacteria from the entire length of the small intestine.

The pill’s protective coating would only melt away once it came into contact with the small intestine’s basic environment, revealing its pores, now open for bacteria collection. From here, Mohammed said, the capsule would pass through the gut, harnessing the stomach contractions that move food through the digestive tract. This motion would also pump bacteria-rich fluid into the capsule’s pores, thanks to the physics of fluid dynamics.

The pill also had to comb for bacteria in the small intestine’s villi — “fingers” that coat the tube’s inner surface — by scraping, but not damaging. Finally, the researchers planned to collect the filled capsules from rat stool using magnets.

Mohammed’s team then tested actual capsules in rodent models. They demonstrated that bacteria captured by the capsules resembled the small intestine’s microbiome much more closely than did traditional stool samples. There was about two to three times greater diversity of bacteria in the capsules than the stool, said Mohammed, representing bacteria from around six phyla compared with two in the stool.

David Relman, professor in medicine and microbiology and immunology at Stanford University, who is involved in research on a similar device, said the capsule “presents an interesting little microenvironment for the contents in the small intestine to fill and colonize.”

But Relman noted that the proportions of bacteria in the capsules did not fully match the bacteria in surgically-removed tissue from the rats’ small intestines. He said that so far, the design of the pill might be better at collecting certain types of bacteria over others.

Mohammed said this mismatch between the pill and the small intestine tissue may also be partially explained by the fact that the tissue collected was only a few centimeters long — itself not representative of the small intestine’s range of bacteria.

Mohammed’s group is continuing to modify the pill’s design to suck up bacteria at a continuous and consistent rate as it moves through the small intestine, as they move onto human safety trials.

“Hopefully you might see it on the shelf sometime in the future,” said Mohammed, who envisions doctors or consumers someday using CORAL capsules to monitor individual gut health. She is currently founding a startup based on the technology.

“Every disease, every issue you have in the body, will create a different microbial profile,” she said. “The more data you get, the more useful it will be.”

Relman agrees, though he takes a longer view. “I’m very positive about this kind of technology, about helping us be more precise and insightful about what is a really, really complicated ecosystem,” he said about the gut microbiome.

But at the moment, Relman said, any information gleaned from the capsules would not be particularly useful. Evidence-based approaches to improve gut health remain eating a healthy diet and avoiding antibiotics when not needed.

“The question is, do we already have the signatures of disease or health that would prompt known beneficial actions by a person off the street?” he said. “I would say we don’t yet have those.”