Chagas disease: the silent killer

More awareness is needed to combat this neglected tropical disease, including in North America

Rachel Nuwer • March 29, 2011

The old house sat on the outskirts of New Orleans, surrounded by brush and forest. Armadillos burrowed under the building, and the windows were often open, welcoming in the sweet southern breeze. In the days following Hurricane Katrina, the 74-year-old resident noticed an unusual number of insect bites covering her torso and legs, once counting over 50 bites, according to a scientist later called to the scene. Streaks of the mysterious culprit’s feces stained the walls and spotted her nightgown and bed sheets. When the insect terminator fumigated her home, the bodies of 20 dead insects turned up. “Those are kissing bugs,” the terminator said.

So the resident went online to discover just what these kissing bugs were. And that’s when she found that kissing bugs are carriers of Chagas disease.

The woman discovered that Chagas disease is caused by infection with the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi carried by kissing bugs, which, like bed bugs, feed off animal blood. Though Chagas most commonly plagues Central and South America, the bottom two-thirds of the United States has active populations of the parasite. So far, about 18 species of mammals — including raccoons, opossums, armadillos and even dogs — have been discovered with the parasite in the United States. Once an animal is infected, it serves as a reservoir for kissing bugs to pick up contaminated blood and infect other animals — or humans — that they bite. When the woman read this, she immediately contacted Patricia Dorn, a fellow New Orleanian and molecular parasitologist at Loyola University who specializes in Chagas disease. Dorn tested the woman and found that she was positive for the Chagas parasite.

Don’t let the kissing bugs bite

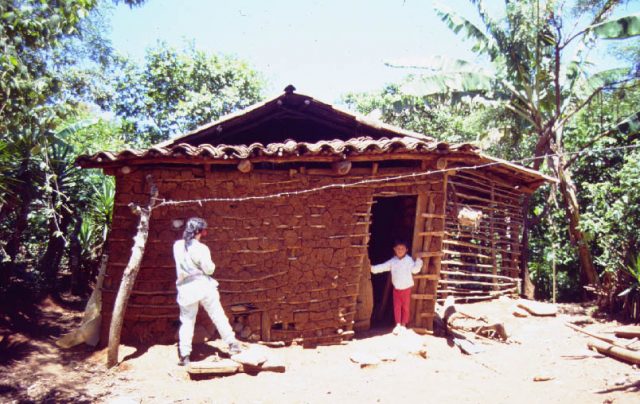

When kissing bugs bite an infected human or animal, Dorn explains, they pick up the T. cruzi parasite in the blood meal. The parasite quickly develops within the bug’s gut. If a kissing bug enters a human home, it spends daylight hours hiding in cracks and crevices; like a cockroach, it likes to be in contact with surfaces both above and below its body. The cracks in the mud walls of rural homes in Latin American provide the perfect hiding place, as do the palm leaf roofs also characteristic of such dwellings. During her work in Latin America, Dorn said she would push against the thatched roofs of homes and “they were just crawling with bugs.”

The kissing bug emerges at night to take its blood meal and often bites around the exposed face of the victim, thus gaining its moniker. While feeding, the bug defecates, its feces teeming with parasitic T. cruzi poised for infection. When the victim scratches at the bite in her sleep, or if the feces makes contact with soft tissues such as the eyes, the parasites then enter the bloodstream. Consuming infected insects or their feces can also transmit T. cruzi, Dorn says. For example, kissing bugs living in the thatch roof of a house may defecate directly into food laid out on a table below. In Brazil, pressed raw sugarcane makes a tasty drink but can also contain the ground up parts of infected kissing bugs.

Chagas disease is referred to as the “silent killer” in Central and South America because it can lie dormant for as long as thirty years. During this time, victims have no idea the parasite is infecting them. When first infected, victims may show very mild flu-like symptoms. In children especially, infections often enter through the eye, causing the eye to swell. The infection, often acquired in childhood, then strikes in the prime of the victim’s life. This so-called chronic stage of the illness manifests itself most often as severe heart disease, Dorn described, enlarging the heart, thinning the ventricular walls, and requiring pacemakers. These symptoms emerge as the parasite moves through different parts of the body, triggering an inflammatory response and causing lesions and fibrosis that kill the cells it comes into contact with. In South America especially, Chagas disease can also present digestive problems, causing some victims’ colons to swell until they are as big around as their upper thighs.

Many victims will remain in an intermediate stage of infection throughout their lives, possibly never suffering from the disease but acting as carriers that donate contaminated blood to passing kissing bugs. This contaminated blood can be unknowingly transmitted to others through blood transfusion if screening is not performed. Infected mothers can also pass the disease on to children during birth. Though effective treatment exists in the early stages of Chagas disease, the therapy often comes wrought with side effects and complications for those seeking help years after infection.

Plague of the Americas

An estimated ten million people are infected with T. cruzi today, mostly concentrated from Mexico to Argentina. Though still a major problem, this figure is a steep drop from pre-1990s numbers when Chagas disease was ranked as the most serious parasitic disease in Latin America and annually infected 700,000 new victims. This changed in 1991 when a major campaign launched by the Pan American Health Organization in seven South American countries aimed to control and eliminate Chagas disease. The efforts reduced transmission of the disease by 94 percent by 2000 throughout the continent, with the number of annual deaths falling from 45,000 to 22,000. By 2001, Chagas disease transmission was completely halted in Uruguay, Chile, and most parts of Brazil and Paraguay.

The health ministries of each country accomplished this feat by screening blood supplies and spraying over 2.5 million homes with insecticide to eradicate the kissing bug vector. But in other parts of South America and especially in Central America, this technique was not nearly as effective since wild populations of kissing bugs naturally occupy the forests of those regions and can’t be sprayed away so easily. Moreover, those most at risk for Chagas disease tend to live in rural communities and also suffer from poverty-related conditions. And despite the improvements, Chagas disease continues to cost an estimated US$1.2 billion loss per year in the Southern Cone of South America alone, according to the World Health Organization.

“The priority in Guatemala is food and education,” said Carlota Monroy, a parasitologist and entomologist at the University of San Carlos in Guatemala. Though Chagas disease is the leading cause of heart disease in Latin America, Monroy explains that the problem does not merit enough attention because people view Chagas “as a disease that they’ll get in ten years, but they need food now.”

Monroy gets around this challenge by addressing several poverty-related problems at once, including Chagas disease. Her projects aim at improving overall health and economic circumstances by simple household improvements using local materials. Spraying homes with insecticide is not a solution since the insects will simply return from the forest in a few months, Monroy explains. Instead, Monroy aims to tackle three major home improvements — patching up cracks in walls, replacing earth floors with concrete, and moving animals like chickens from inside the house to outside. These adjustments also exclude other disease-causing parasites. Local women take charge in making these projects a success, Monroy says, as they readily participate in home improvements to create a cleaner house and healthier children. Monroy provides wire mesh for building animal pens and long-lasting, durable local materials for replacing the floor and patching up walls.

Researchers search for kissing bugs hiding in wall crevices of Guatemalan homes [Image Credit: Patricia Dorn]

Still, Monroy says, this project has only been implemented in about six villages with thousands more on the waiting list. Organizing resources and finding adequate funding remain major challenges. And as forests are cut down and nature is destroyed, she explains, more and more insect vectors enter Guatemalan homes, looking for environments similar to those they would normally inhabit, like tree holes or animal nests. The bugs naturally occur around us in the environment, Monroy says, “we have to find a way to live with them without letting them invade our houses.”

Meanwhile, similar situations exist in neighboring countries. “The bugs don’t have passports,” Monroy says. Researchers must come up with novel ways of combating the insects tailored to local circumstances.

In the Mexican Yucatan, insecticide use is also futile since kissing bugs naturally occupy forests, says Eric Dumonteil, a French parasitologist at the Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan. Although Mexico lacks well-established national health programs and also does not have data for the distribution of the disease throughout the country, the most conservative estimates say one to two million Mexicans carry T. cruzi in their bloodstreams, Dumonteil says. With funding secured from the World Health Organization, Dumonteil is doing what he can to control the disease and raise awareness. From initial studies, he found that insect screens and curtains impregnated with repellent seem to work well in discouraging kissing bugs from entering homes. He is also beginning educational campaigns in local communities. While most people know that kissing bugs bite humans, he says, “what they don’t know is that it can transmit the parasite and cause Chagas disease.”

In South America, while overall circumstances have improved since the 1990s, congenital transmission is still a serious problem. In Argentina, for example, 3.5 percent of all pregnant women are infected with Chagas disease and often pass the infection on to their infants through the placenta or during the birthing process, says Sergio Sosa-Estani, an epidemiologist who is director of vector-borne disease research at the Ministry of Health in Argentina. Though Argentinean law requires that pregnant women get tested for the disease, he explains, sometimes it is a challenge broadcasting this message, especially to remote parts of the country. Sosa-Estani says that treatment for infants born with Chagas disease is almost 100 percent effective, but as a child grows, that efficacy drops. The main gap in Chagas control in Argentina is completing the follow-up treatment of children born to infected mothers, Sosa-Estani says. This poses one of the last great challenges for controlling Chagas disease in Argentina.

Closer to home

Only seven cases of Chagas disease transmitted from kissing bugs to humans have been documented in North America, but that does not mean the problem is trivial. An estimated 300,000 infected persons currently live in the United States, mostly of immigrant background, and thousands more have carried the disease to Europe, Canada, Australia, and Japan. But awareness of Chagas disease in the United States remains extremely low, Dorn says. “I think probably some people die of heart disease and no one ever suggests that they actually die of Chagas,” she said. Spreading awareness of the disease is tricky, though because it could cause an anti-immigrant backlash. “We need to address their needs without ostracizing them,” Dorn says.

Only one treatment center, in Los Angeles, exists in the United States specifically targeting Chagas disease. The Red Cross and Centers for Disease Control founded the center after a 2007 Red Cross initiative to screen blood donations for T. cruzi found numerous positive tests, but there was nowhere to send patients for treatment. “We have the bug and we have the parasite, and people in the United States have Chagas, but no one’s testing for it,” says Dr. Sheba Meymandi, a professor of medicine at the University of California Los Angeles and director of the Center of Excellence for Chagas Disease.

In 2001, the prevalence of Chagas disease in Los Angeles heart failure patients was 4.6 percent, Dr. Meymandi reports, and in 2010 it was up to 17 percent. Patients who have Chagas disease have much more severe cardiac disease, with a nine-fold increase in morbidity and mortality compared to those suffering normal heart failure without Chagas complications. In the general Latin American population of Los Angeles, Dr. Meymandi has found that a little more than one out of 100 people are positive for T. cruzi. “There’s no awareness of how prevalent it is in the United States,” she says. “I’m sure if this was a disease in the affluent population you’d have a lot more people interested.”

This could change soon, though. Dr. Meymandi reports that two high school students recently came back positive for T. cruzi after attempting to donate blood at local drives. Neither of the patients is Latino nor has either ever been out of the country, though both are fans of outdoor sports and thereby could have been exposed to infectious kissing bugs while out in the elements. Indigenous populations of infectious kissing bugs do occur in the southern United States, as Dorn and other’s work has shown, so if circumstances allow for exposure, catching Chagas disease from natural vectors comes as no surprise. To treat such cases, though, Chagas disease must first be recognized and diagnosed.

Dr. Meymandi believes heart failure due to Chagas disease can be prevented if it’s treated early enough. But treating Chagas disease comes with a host of problems. The two treatments available, benznidazole and nifurtimox, are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and prescriptions need to be filled directly by the Centers for Disease Control rather than through a normal pharmacy.

Patients must consent to undergo treatment under an investigative protocol and must get sponsorship from a pharmaceutical company. Though the drugs seem effective for curing the disease in the early stages, for those infected for ten years or more, treatment tends not to work so well. Severe side effects often accompany therapy, and even after enduring the 60 to 90 day regime of medication, the parasites sometimes hide deep in heart tissue, shielded from the drugs, only to emerge again later.

And people aren’t the only ones suffering from Chagas disease. Dogs are an important reservoir of the disease, especially because they are close to their human owners, says Prixia Nieto, a veterinarian originally from Colombia based at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. Neito studied a population of high-risk dogs in Louisiana — usually those that are kept outside in kennels and often used for hunting — and found that of 160 dogs, 22 percent were positive for T. cruzi. Similar to their human counterparts, Chagas-infected dogs may suffer from sudden heart failure. Not many veterinarians are aware of Chagas disease, explains Nieto. “They think that it’s something that happens in Latin America and just in humans,” she says. Even for those veterinarians who are savvy to the disease, diagnosis requires sending blood samples to the Centers for Disease Control. If a dog does carry the Chagas parasite, treatment for the symptoms is available, but Nieto says that American owners are oftentimes so afraid of the strange disease that they have the animal put down even though transmission directly from dog to human is impossible.

Chagas disease continues to infect large numbers of predominatly poor people in Latin America and is becoming an increasing presence in North America due to immigration. Treatment for the disease remains difficult and sometimes even impossible, but improvements are being made. Despite the remaining challenges for controlling Chagas disease, things are getting better.

It’s been about 100 years since the disease’s discovery by Carlos Chagas, Dorn says, and in the past five to ten years there has been a tremendous increase in interest, research and publications revolving around Chagas. For example, Dumonteil in Mexico recently received funding to try to develop a preventative and therapeutic vaccine for T. cruzi. He has already shown that it can work in mouse models and hopes to have it ready for human trials in about three years. And as for the infected woman in New Orleans, “she is currently very well,” says Dorn, though she opted against treatment.

For now, dragging the silent killer out of the dark and into the medical spotlight seems key. “There needs to be a huge campaign to increase awareness,” says Dr. Meymandi, “The awareness is the limiting factor.”

11 Comments

It is ironic that I happened upon this article. Just a few days ago, I saw another article on “beneficial insects.” It mentioned the benefits of the assassin bug (they kill other bugs that are undesirable), which appears very similar to the kissing bug pictured above. A web search indicates that they are the same.

I saw TV special on kissing bugs when I was young, seven or eight years old; I was terrified of kissing bugs for months.

Two of my co-workers had just gotten back from Guatamala. I was told the story about the kissing bug and decided to look it up….wow! Bueno suerte Eric Dumonteil!

In the late 80″ early 90’S I was bitten several times (6) by the kissing bugs in Don Pedro California. Made several trips to the emergency room with blood poisioning and the last time almost didnt make it. I saw a news cast on fox news about Chagas Disease,and became very nervous as myself and my sister were told we made have the disease. Scary Stuff.

I just got bit by one of these. Caught it and took it to the DR. she didnt recognize what the bug was. It hurt when it bit though- stung like a scorpion for an hour and a half. I killed it and kept it. Should I pursue this further?

Jessica, call your health department. Texas Health dept Zoonosis section will test the bugs.

Also, check the CDC website.

Hw can i get tested for this as i think i might have it and my current doctor clueless? Please help. P.a. Im in australia

I was bitten by one of these several years ago and the bite continues to become enlarged every so often, is hard in the center and something like a grain of sand comes out of it. It will heal up and then a month or two later, it will do it again. I’ve been to a dermatologist who checked for cancer and said it is nonmalignant. Could this be a manifestation of the kissing bug bite?

WOW just what I was searching for. Came here by searching for Business Electricity

Armadillos are a source of leptospirosis in Africa.

The Following Year, he’ll be seen playing a gangster in Vetrimaaran’s two-part movie Vada Chennai”.