A Modern Plague

An encounter with MRSA, the scourge of the health care world

Mary Beth Griggs • January 4, 2012

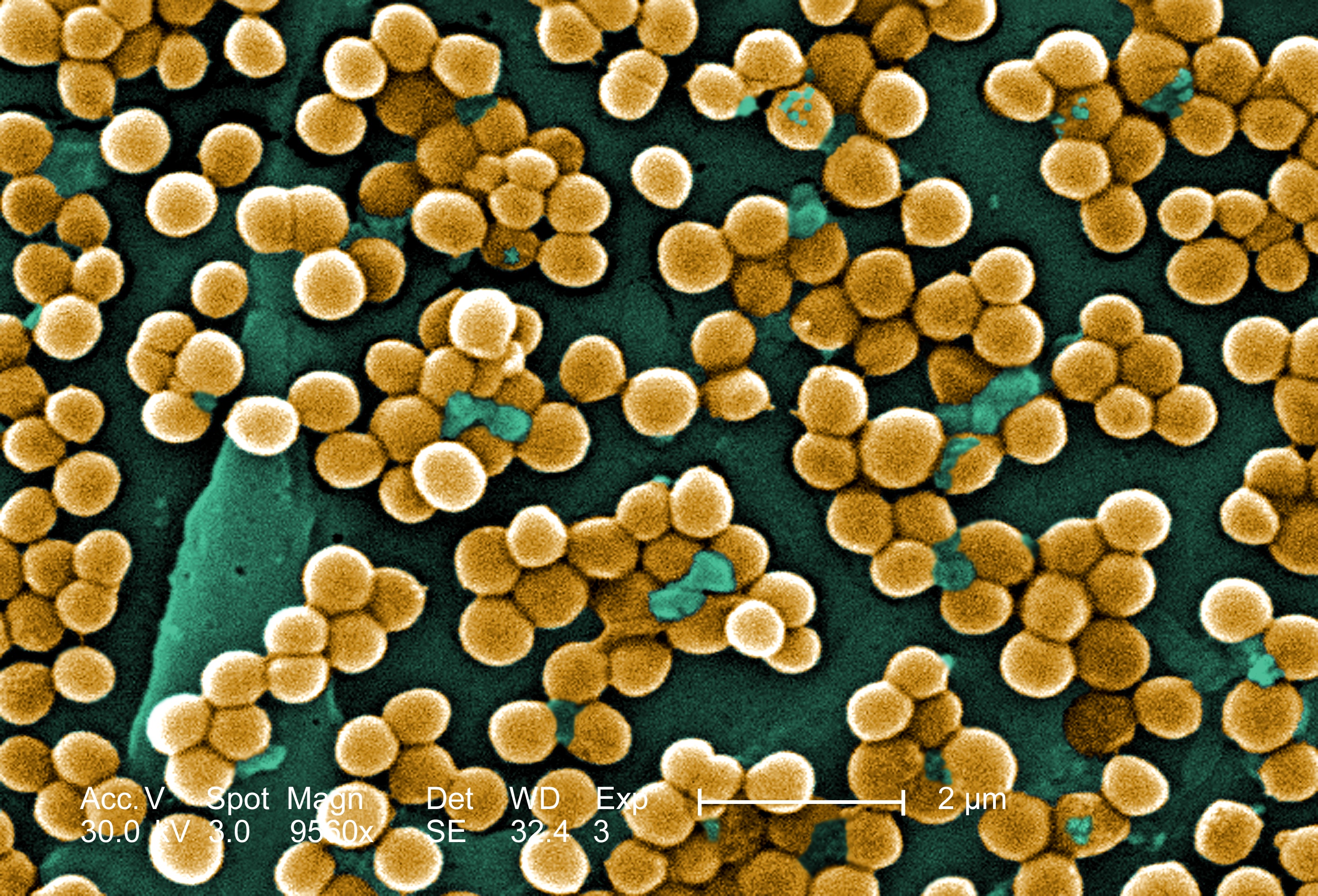

A microscopic image of the bacteria Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA [Image Credit: CDC]

The gown was a sickly yellow.

Not a bright and sunny yellow, or a lovely pale yellow that flatters those fortunate enough to have the proper skin tone, but a sickly, nasty jaundiced yellow.

“At least no one would ever forget to take it off,” remarked my mother. And this was true. The color of the hospital gowns would look horrible on anyone, making it easy to remember that the gowns, and their companion gloves, must be thrown out as we left my grandmother’s hospital room.

My family of four wrestled to properly gown and glove ourselves so that we could enter my grandmother’s hospital room. When we left we carefully peeled off the extra layers, tossing them into the specially labeled garbage can nearby. The elaborate ritual of swathing oneself in disposable latex, paper products and Velcro had to be rigorously observed every time a nurse, doctor or visitor entered and exited the room.

No exceptions.

No one wanted to spread MRSA around the hospital, or out into the world.

The Bug

MRSA, or Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is now a common topic of conversation in my family. But when my 82-year-old grandmother came down with it in September of 2010, I had no idea what it was. I half-remembered news reports of something bad, some new disease that lurked in hospitals and gyms, and I remembered that the R stood for “resistant,” but I knew nothing else.

My ignorance was quickly remedied.

I found out that MRSA was a drug-resistant strain of the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus); small spherical bacteria that could cause infection if they ever got into a cut or into the bloodstream.

“It can live on your skin but most people believe that it needs warm, moist environments to thrive — most frequently we think about the nose,” says Dr. Alexander Kallen. Kallen, a medical epidemiologist and outbreak response coordinator at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has written numerous papers on MRSA.

MRSA spreads through human-human contact, otherwise known to the nonprofessional as “touching,” which is why disposable gloves and gowns are required attire for anyone visiting a MRSA patient. It isn’t an airborne contagion, so no masks are required, though after hearing about the symptoms of a MRSA infection, I almost wanted one, just in case.

“MRSA infections tend to be relatively necrotic looking,” says Kallen. He described them as “spider-bite–looking things that have pus, boils and abscesses.”

The MRSA wound on my grandmother’s foot was much more than a “spider bite.” At its worst point, even high doses of morphine couldn’t dull her pain. The skin blackened, it was draining pus every day and the bacteria had eaten away at the flesh. So much flesh was missing that the tendons of her foot were exposed to the air, and her doctors lived in fear of acute osteomyelitis, or bone infection. My aunt put it bluntly: “There’s a hole in her foot.”

Location, Location

We’re still not sure where my grandmother got it. Until she came down with MRSA she swam laps almost every day and lived in an independent living facility with her own apartment and car. It started late last August, when she found a small but painful abscess on her foot. The doctors originally diagnosed it as gout, a disease that she had experienced before.

Gout is typically associated with rich foods and royalty, and this diagnosis convinced my grandmother that she had gotten gout from eating a particularly good lamb chop a few days before the diagnosis.

But alas, the lamb chop was innocent. “It is sometimes difficult to differentiate infections from gout,” says Kallen. Gout isn’t an infection at all but rather, the inflammation of joints caused by uric acid build-up — still painful, swollen and nasty, but not infectious. Soon enough her doctors realized that they were dealing with something far more serious. Something linked not to lamb chops but to her environment.

A MRSA infection can be contracted in two very different settings. It can originate from a community area, such as a school, gym or prison, where lots of people are crowded together and there are lower standards of hygiene. As it happens, my grandmother’s adoration of her daily swim stemmed not only from a desire to exercise but also from a love of the showers at the community center. They had good water pressure and were large and private enough that an elderly lady with poor mobility could navigate them easily. Their damp warmth was also exactly the kind of environment where MRSA could thrive.

Far more commonly, though, MRSA can originate in a hospital or health care setting.

MRSA’s biggest weapon against us is its ability to resist antibiotics, and for S. aureus, hospitals are the perfect training ground to learn how to fight anything that we might send to battle against it. The M in MRSA indicates that it has already defeated our first champion — methicillin, and its antibiotic cousins in the penicillin family.

“Hospitals are where a lot of antibiotics are being used. [They] kill off all the sensitive bacteria that are out there,” Dr. Elizabeth Bancroft, an epidemiologist with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. “It’s survival of the fittest.”

There are still some antibiotics that work against it, but MRSA’s adaptive nature means that in hospitals, MRSA can grow into stronger, more-resilient strains that can pass from person to person in a comforting touch or from patient to patient by a physician’s caring hands.

Colonies of MRSA

I was skeptical when the nurse at my grandmother’s hospital told me that I probably had MRSA too. “You probably have it in your nose honey — most people do,” she told me. But when I asked her for details, she shrugged. “Some people it doesn’t affect as much,” she said, and hurried off on rounds.

I decided to find out more information, and discovered that the nurse was absolutely right, if reluctant to waste time instructing irritating family members on the details of infectious disease. There was a big difference between colonization and infection — and when most laypeople refer to “having” a disease they mean they are infected with it. But MRSA is a bit more complicated than that.

“Many more people are colonized with Staph. aureus then will ever be infected,” says Kallen. He estimates that around 30 percent of the United States population is colonized with S. aureus, and that 1 percent to 2 percent of the population is colonized with MRSA.

In a population of approximately 300 million, that means that maybe 3 million people are colonized with MRSA, and 93 million are colonized with the not-as-resistant S. aureus. These numbers may seem frightening, but they illustrate the difference between colonization and infection.

The primary difference is quite simply, there aren’t 3 million cases of MRSA in the United States right now. Instead there are approximately 90,000 cases per year — a concerning but much lower number. The reason for the discrepancy is that most people colonized with MRSA never give it the chance to become an infection. It stays on their skin or in their nose, but these carriers aren’t constantly hooked up to IVs, or getting cuts and scrapes right before entering a sweaty locker room. They aren’t at a high risk of infection from the population of MRSA that they’re carrying.

But other people are.

Preventative Care and the Elderly

Elderly people, including my grandmother, are at higher risk for MRSA infections than the rest of the population because of their increased contact with health care facilities. As people get older and their bodies begin to age, they often need more health care. The census bureau reported that in 2009, 95.3 percent of the population over 65 years old went to a health care provider at least once, and 60.6 percent visited a doctor or hospital four or more times.

During her long months of MRSA treatment, my grandmother was also treated for a hip that got broken twice, hypertension, renal failure, depression, muscle weakness and a handful of other infections and conditions.

This litany is not uncommon for an elderly patient. “There are a lot of issues with the elderly, and their bodies and immune systems,” says Bancroft. And they are at a much higher risk of getting MRSA.

The gown and gloves are just part of the steps that hospitals all over the country have taken to ensure that MRSA will not spread among its most vulnerable patients. These physical barriers are a first line of defense against a disease borne by touch but are certainly not the only preventative measures.

Reducing unnecessary needle sticks, or the length of time that patients spend on an IV drip or central line, allows patients to regain their natural defenses more quickly.

“Normally your body has a barrier between yourself and the outside, but in the hospital that barrier is broken,” says Bancroft. Limiting the breaches to this barrier helps to limit MRSA infections.

But both Bancroft and Kallen agree that one of the primary bulwarks of defense against MRSA is simply washing your hands.

“If you think about it, your hands are little ambassadors to the world,” says Bancroft. “Every time you go to a new country, a new patient, you have to go through customs. You have to wash your hands,” says Bancroft.

Hospitals have tightened their defenses so much that the disease is actually receding in health care settings, decreasing by as much as 9 percent annually from 2005 to 2008, according to a 2010 CDC study. This is good news, allowing medical professionals to focus on more community-centered locales. such as nursing homes and other areas for long term care, where the disease is slowly encroaching.

“I think that at CDC we’ve historically been focused on acute-care settings. But more and more, with multi-drug-resistant organisms it’s a problem across the whole spectrum of health care, and long-term care is a part of that,” says Kallen.

Comparing hospitals to nursing homes sheds some light on the different levels of protection and prevention that can be taken to combat MRSA. In an “acute-care setting” like a hospital, infections can be tightly and narrowly contained under strict protocols.

A nursing home is different. Its residents are there for much longer periods of time, and they need to socialize and have routines — activities that struggling in and out of a gown and gloves fail to easily facilitate.

Since residents in nursing homes tend to be more mobile and have fewer health complications than hospital patients, they have a much lower risk for MRSA. Most nursing homes have taken this into consideration, and so long as a resident is able to contain their MRSA infection under a clean bandage, they are allowed a little less isolation. They can leave their room, or have visitors enter it as long as the infection is contained and everyone washes their hands.

Just thinking about how to deal with infections like MRSA in nursing-home settings is a huge shift for groups like the CDC. “It’s a fundamental change in the way we approach this infection, not just here but across the whole country,” says Kallen. An expert review of MRSA-prevention in nursing homes found a surprising lack of studies focused on this vulnerable subset of the population and recommended the following: “Rigorous studies should be conducted in nursing homes, to test interventions that have been specifically designed for this unique environment.”

For months, nursing homes and their isolation protocols became the new buzzwords in my family. The home that my grandmother was moved to had more relaxed isolation protocols. They were lifted completely around Valentine’s Day.

Her MRSA diminished along with the protocols. She had repeated negative tests at the wound site, and the horrible gaping wound on her foot healed to a mere scab.

But the long months of MRSA and the complications that came with it took their toll. When I spoke to my mother in March, she reflected on the speed with which the disease exacted its terrible price. “Last August she was independent” said my mom. “But now she’s in full time nursing care… and it all started with that foot.”

Authors Note: This article was written in early 2011. While it was being prepared for publication, my grandmother’s health began to fail again, the MRSA came back, and she was returned to the hospital. I decided to hold off on publication. She passed away on Easter day, after a long struggle with MRSA, among other ongoing conditions. My family and I miss her dearly.

3 Comments

In acute care settings, Active Detection and Isolation can drop Hospital Acquired MRSA cases by 50%…as proven in the VA Hospital Study. By knowing who is colonized and separating them from the general patient population, using decolonization for pre op and some other patients, and by using the appropriate pre op antibiotics to ward of active MRSA, many, if no most, hospital acquired MRSA cases can be prevented.

My father died of Hospital Acquired MRSA pneumonia January 2009. HIs original hospitalization was for a minor ankle fracture. 12 days of rehab in his hospital resulted in his infection, rapid decline and death all within a few months.

One of the least well kept secrets is that an old medical technology called phage therapy will work on many infections when antibiotics fail. If you google ‘phage therapy’ a wealth of information will come-up. Here is a specific paper on MRSA and phage therapy:

Phage therapy of staphylococcal infections (including MRSA) may be less expensive than antibiotic treatment, R Międzybrodzki, W Fortuna, B Weber-Dąbrowska…

Here are some references to the latest scientific information on phage therapy:

Thomas Haeusler. 2006. Viruses vs. Superbugs, a solution to the antibiotics crisis?

Monk, et al. 2010. Bacteriophage applications: where are we now? Letters in Applied Microbiology, 51, 363-369.

Kutter, et al. 2010. Phage therapy in clinical practice: Treatment of human infections, Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 11, 69-86.

Bacteriophages in the Control of Food- and Waterborne Pathogens, Editors: Parviz M. Sabour and Mansel W. Griffiths, ASM Press, 2010.

Killer Cure: The Amazing Adventures of Bacteriophage (Canadian-made movie)