The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain

“Part of what you do is this typical British thing where part of your r sound is more like an ‘aaarh.’” I have never really wanted to change my British […]

Benjamin Plackett • January 5, 2012

“Part of what you do is this typical British thing where part of your r sound is more like an ‘aaarh.’”

I have never really wanted to change my British accent, but if I ever did, I would go to see Diane Boardman. In her office, the scene of many modern-day “My Fair Lady” productions, Diane plays Henry Higgins to her clients’ Eliza Doolittles, changing their accents for what they hope is the better.

Diane, a speech pathologist and therapist, meets clients on a weekly basis in her Queens home, which she shares with her husband, Ken, and cat, Lola.

Although she also helps patients with medical problems that cause speech impediments (that’s the pathology part), her clientele are mainly expatriates who want to sound more American (that’s called training). She says that many of her clients worry that their accents are holding them back, especially in their professional lives. Diane is aware of certain prejudices that society can hold against regional accents and so has toiled to standardize her own accent. Now 62, she is a proud “Jewish New York City girl” who grew up in Flatbush, Brooklyn. Occasionally, she reveals her origins by letting a slight Brooklyn twang slip past her composed accent.

Diane with Jorge, a client from Colombia [Image Credit: Benjamin Plackett]

I sat in on a speech therapy session with Diane and Jorge, a 39-year-old client from Colombia who has been coming to Diane for about two months. He explained that his “dream has always been to speak good English.” Although he has lived for seven years in New York, he still struggles with vowel sounds. He hopes that working with Diane will open new opportunities, which he believes remain closed because of his accent.

But Diane cautions her clients that they must be realistic about how much they can change their accents. “You’re not going to sound like you were born here,” she tells them.

Diane did not dream of being a speech pathologist as a child. She dreamed of being a dancer, which she pursued and achieved through hard work.

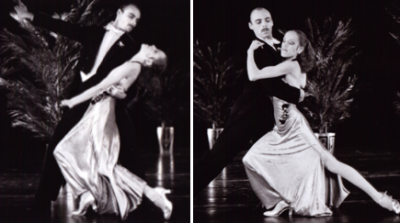

1975: Diane with her dance partner Vick, dancing for the Phyllis Lamhut Dance Co. [Photo Credit: Tom Caravaglia]

Phyllis Lamhut, a former dance instructor and life long friend, says that Diane stood out among her students. “She was a beautiful dancer … she worked very hard”. Phyllis was so taken with Diane’s dancing abilities that she often chose Diane to understudy her own roles in the dance company.

When she was just 4 years old, Diane went to see “The Nutcracker” at the New York City Center. “I was way up in the nosebleed section, and I just remember this illuminated rectangle,” she recalls. The rectangle was the stage and her mom asked if she wanted to dance like the performers who twirled across it. She said yes, and they looked for a dance teacher. By age 5 she was dancing for Phyllis.

In her late teens Diane opted to stay at home and take the bus to Brooklyn College. She says that Brooklyn College had little respect for dance as a discipline. “They gave so few credits to the dance courses that I would take between six and eight courses a term” just to graduate.

After graduation she went on to enjoy a successful dance career, although it was hard “especially on my bank account,” Diane says. She received grant money from the National Endowment for the Arts, toured throughout the United States, and had her choreography performed in Europe.

As her body aged, Diane grew frustrated that it could no longer do exactly what she wanted it to. She looked for a new career.

As a dancer Diane was used to hard work. So when it came to changing careers, she was psychologically well equipped to deal with the “tough process” of studying for a master’s in speech pathology at Queens College. She smiles cheekily and lingers on the o in “process” so as to gently mock my English accent.

The “long-distance run,” as she calls it, from dance to speech therapy was not as convoluted as one might assume. She uses the same sense of rhythm and melody as she did back in her dancing days. “Language has a rhythm” she says. “When I work with people for accent modification I look for their melody.”

She poked fun at my accent throughout the interview, so I guessed she had found my melody, I ask her if we can try changing my accent from English to American? She smiles. “So tell me, what is this?” She points to her ear. I reply: “your ear.” She laughs and mimics me saying “eeaaaaaaaarh.”

Diane says that there are two main things that I (and other Brits) do differently than Americans when we pronounce words: the r sound and the u followed by r sound. She explains that when Americans say words with u followed by r it is called the “weight lifting sound because it is “’ugh ugh,’ like when you work out.”

I repeat a sentence back to her — “My ear hurts” — apparently in a passable American accent. “You’re a good student!” she replies.

It is clear that Diane enjoys what she does, and her sessions are full of such banter. “But does speech therapy live up to her former dance career?” I ask. The smile fades. She preferred her life as a dancer, she says, adding that she can bump into an old dancing friend after years and it is as if they were never apart. “There is such a camaraderie between people who dance together,” she says. “[Dancing] was not just a job, it was [my] way of life.”

1 Comment

Such an interesting story. It makes me wonder if there are speech professionals available to help native English speakers modify their accents while speaking Spanish or French?