Science cartoonist Sidney Harris doesn’t draw “funny style”

Harris communicates science with minimal line work

Rebecca Cudmore • January 31, 2014

"Krill Small Talk…" by S. Harris [Image credit: Sciencecartoonsplus.com]

Right off the bat, Sidney Harris makes it clear that he’s not a scientist. He’s a cartoonist who grew up in Brooklyn and drew for Playboy but somehow he still knows about neutrinos and the beginning of the universe.

“I get the gist of it,” says Harris. “Neutrinos come from outer space. They go through everything, there’s a billion of them going through my hand right now… maybe?” He laughs, “I don’t know.”

Harris isn’t just any cartoonist. He’s drawn over 34,000 cartoons during his near 60-year career for outlets like American Scientist, The New Yorker, Discover and Science. And he’s published handfuls of cartoon books covering a wide array of themes: His latest mocks America’s filthy food industry.

Cartoonists are basically dilettantes. “We know a little about a lot of things,” says Sam Gross, a cartoonist for the New Yorker who’s known Harris for 50 years and still meets him for French food on 46th Street in Manhattan each week. “But with Sidney, as far as the science is concerned, he knows a lot more than a little bit.”

Now in his 80s (he won’t give his exact age), Harris claims he’s never held a real job. He recounts one bout of semi-employment with Rapid Messenger Service on 40th Street. “I don’t know if you’d call it a job,” says Harris. “I don’t even know what was in the messages, I just delivered them.” He could only stand the position for a couple of weeks before quitting.

Nowadays, Harris pokes fun mainly at outer space and the principles of physics. Though he claims he’s never taken a physics class, his mind retains a collection of essential and quite elegant scientific facts (or rather, “factoids,” as he calls them). Factoid number one: An atom is mostly open space. He once read that if not for that space between the elementary particles in an atom, the Empire State Building would be the size of a pill. “This is made of atoms and it certainly seems solid,” Harris says, knocking his fist on a wooden desk. “And the neutrinos know that, they just go right through!”

Harris left the bustle of New York City 26 years ago and has lived in New Haven, Connecticut ever since. His house here resembles a maze, as if designed for his own entertainment. The upstairs studio where he works is accessible from two different staircases, each lined with a hodgepodge of paintings and framed cartoons. The first upstairs room is littered with misplaced mail, pens without caps and baseball figurines—his love for the Dodgers he calls, “sort of a religion.”

Harris in one of his drawing rooms, where he says he “doesn’t spend enough time.” [Image credit: Becca Cudmore]

In the next room, Harris plops into a whirly chair in front of his desk and grabs a fountain pen. This is where he draws most every Saturday and Sunday. A college-ruled notebook sits on his desk, about a quarter full of identically-spaced cartoon ideas, with the first page reading: October 2011. “This is all I did in two years,” he says. “Pretty skimpy.” He has piles of these notebooks, dates scribbled across each cover going as far back as 1955.

Harris’s cartoon inspiration comes from reading major scientific magazines, newspapers and books, but his wry sense of humor comes directly from daily life. He can’t help but see the underlying irony and hilarity of the seemingly mundane—in fact, he even cherishes samples of people’s handwriting. A piece of notebook paper on Harris’ studio door is covered in signatures he’s cut from checks people have paid him throughout his career. Truly tickled by each autograph, he points out the silly loops, waves and sometimes single lines, questioning if many of them can still qualify as a person’s name. Harris refers to his own technique as mainstream and makes it understood, “I don’t draw funny style.”

Gross says Harris’s work is so distinct and easily recognizable that “he doesn’t even need to sign it.” In fact, his drawings employ minimal line work and are quite simple—in contrast to their scientific humor.

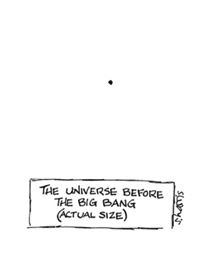

“The Universe Before the Big Bang” by S. Harris, with the black dot. [Image credit: Sciencecartoonsplus.com]

Perhaps the most minimalist of all, “The Universe Before the Big Bang” (shown “actual size”) appeared as a full page spread in the magazine Science 80 and was included in the second edition of his book, “Einstein Simplified.” In the midst of producing the book, the printer thought the single dot was a smear and eliminated it. They printed 7,500 copies with the mistake, says Harris, and the publisher had to recall all of them and re-stamp every single dot back onto each drawing. This finicky cartoon is the likely offshoot of Harris’s second favorite factoid: Until the time of the Big Bang, there was no such thing as space. “We just can’t understand that,” he says.

Though Harris wouldn’t call cartooning a passion, it’s not exactly work for him either. He says he just “knows how to do it,” so he does. In fact, his favorite part is coming up with the ideas themselves. “But the drawings. It’s like, ugh, I’ve got to do the damn drawing now.”

If Harris were ever to have a “real job” he might be a file clerk. “I’m so good at organization,” he says. And it’s easy to see: All of Harris’s drawings are cleverly archived by cartoon subject in a stack of file cabinets within his studio.

Looking through these cabinets of old cartoons, Harris admits that he doesn’t remember most of them. The stuffed drawers are a tribute to his prolific career, but at the same time a reminder of his age—and Harris isn’t too excited about getting old. He describes waking up a few months ago in the middle of the night, thinking he was 20 years younger. “I woke up and I was like, oh well that’s not so bad. And then whoop! It was a dream.”

Despite the frustration, Harris can’t help but be entertained by, and even a little in awe of, his own age. He points to an archived photo of himself in his 20s, then quickly yanks up a shirtsleeve—“See! I still have black hair”—drawing attention to the dark hairs on his forearm, in contrast to the white hairs on his head. He looks astonished: “Isn’t that interesting? I find that amazing.”

And perhaps it’s just this that keeps Harris young: his relentless ability to be amazed. Harris jumps to factoid number three: “Matter is solidified light. I don’t get it. But isn’t that wonderful, if it’s true?”