Under blue skies

New images of Pluto may hold clues to the origin of life on earth

Dyani Sabin • November 9, 2015

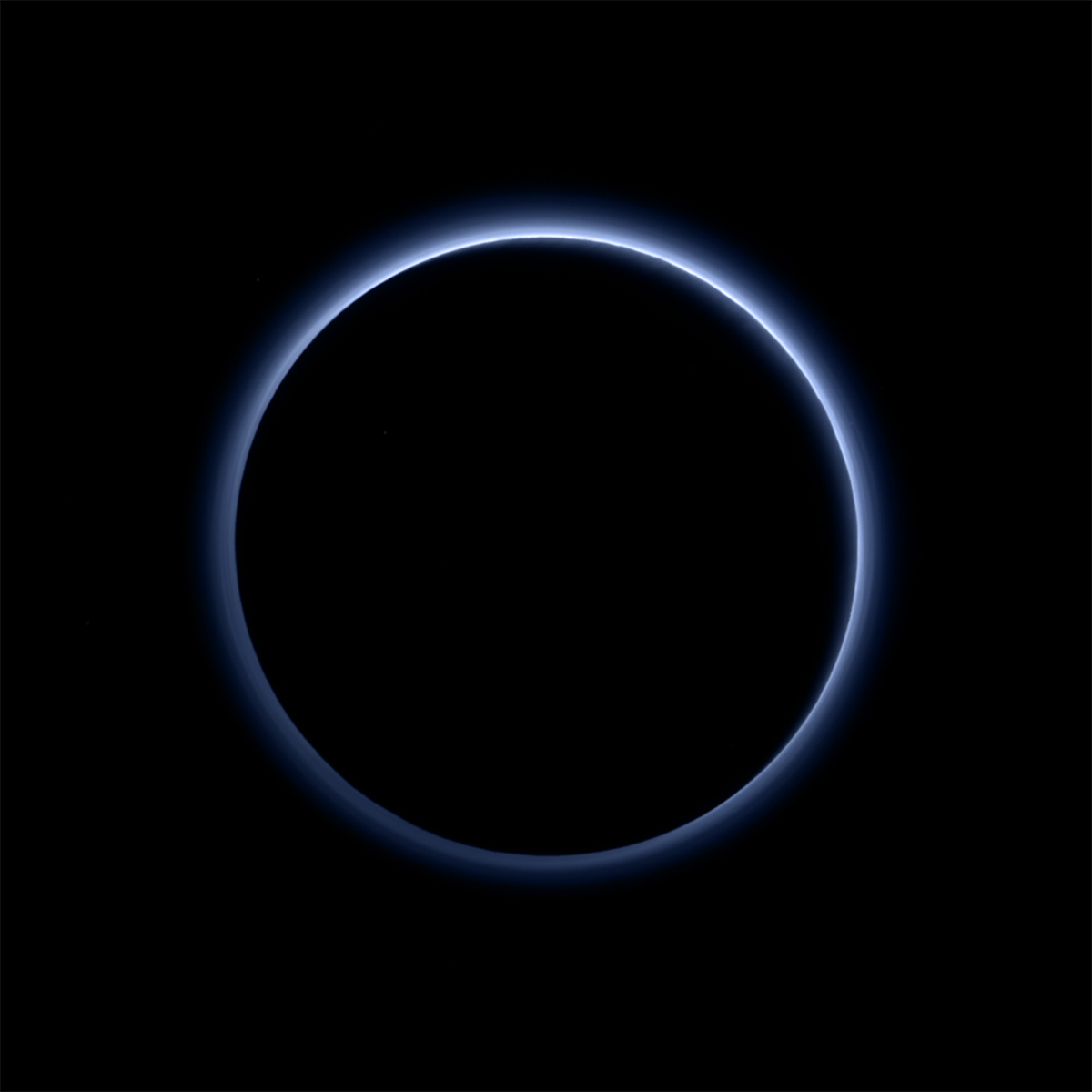

Pluto’s blue sky comes from a smoggy haze of red-hued particles that resemble the building blocks for life on Earth. But don’t get your hopes up for life on Pluto. Taken by the New Horizons Ralph/Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC). [Image Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI ]

A new photo of a blue halo around Pluto created a cackle of excited tweets from NASA’s New Horizons team as its scientists started analyzing the blue skies and red ice photographed during their spacecraft’s July flyby.

Pluto’s blue sky, NASA explained, is caused by smog-like particles called tholins, which are also responsible for Pluto’s red surface. While it’s unlikely that there’s life on Pluto, the color change from Pluto’s blue atmosphere to its red surface indicates the chemical transition of tholins from simple smog to large, complex compounds. This process may have played a role in the origin of life on Earth, according to a study published in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Tholin is not a terribly specific term. It’s about as descriptive as calling a salad a food, wrote Sarah Hörst, a professor at Johns Hopkins University who studies the atmospheric chemistry on Titan, Saturn’s moon. There are thousands of variations of what a salad is — from bean salad, fruit salad, to simply lettuce and tomatoes. The word gives you a general sense, but it doesn’t really tell you a lot about the ingredients. Similarly, ‘tholin’ is a broad term for hundreds of thousands of chemical compounds, ranging in size and color, grouped together because of a vaguely similar structure.

Building a tholin is a roughly standard planetary practice, and the structure that forms tholins allows them to reflect light in a similar way. In the nitrogen-heavy atmospheres of two of Saturn’s moons, Titan and Triton, ultraviolet (UV) light hits methane and nitrogen to start a chain of reactions creating increasingly complex carbon-nitrogen molecules. On Titan, the tholins’ final products are larger than 80 carbon molecules. A molecule that size does not interact with light the same way our atmospheric oxygen does; if oxygen is an eagle, tholin is a Boeing 747.

In Earth’s atmosphere, the Sun’s UV light hits small molecules like oxygen and nitrogen, scattering bluer wavelengths more than redder wavelengths, causing the sky to appear blue. Typically, when UV light hits a larger tholin molecule, it acts more like it hit a cloud, producing a white-colored light. But because of the structure of tholins, UV collisions also causes a slight blue haze. This effect is particularly noticeable in polluted cities on Earth, where the scattering in smog makes sky colors more vivid.

But on Pluto, where a lack of oxygen helps form the biggest tholins, the effect is even more prominent. These large tholins are the same ones that formed on Earth four billion years ago and created compounds that researchers think were essential for life to begin. So while we can’t breathe the atmosphere on Pluto, its blue smog gives us some new insight about how life may have begun on Earth – and perhaps on other worlds where we might someday find life, like Titan.

Astrobiologists get excited about tholins because of what happens when the compounds get larger and heavier, falling toward the planet’s surface and smacking into other tholins along the way. On Titan, researchers discovered that this process formed 18 amino acids and nucleic bases. On Pluto, we know that the process also goes this far, because New Horizons spotted the distinctive red tholins on Pluto’s icy surface. The dwarf planet’s red hues looked similar to the colors seen on Titan by NASA’s Cassini probe.

The layers of pre-life compounds that cover the surface of Pluto help support the idea that something similar might have happened on Earth. As these complex molecules first settled into our planet’s early oceans billions of years ago, they may have formed the amino acids and nucleic bases that were the building blocks of proteins and DNA of early life – and of us.

3 Comments

Great story!

Great piece. I especially like the eagle and Boeing 747 analogy!!

I’ve never heard of tholins, but your writing was very effective in helping me understand their importance. Good job!