The F-Block: Uranium

The f-block's Madonna

Ryan F. Mandelbaum • March 16, 2016

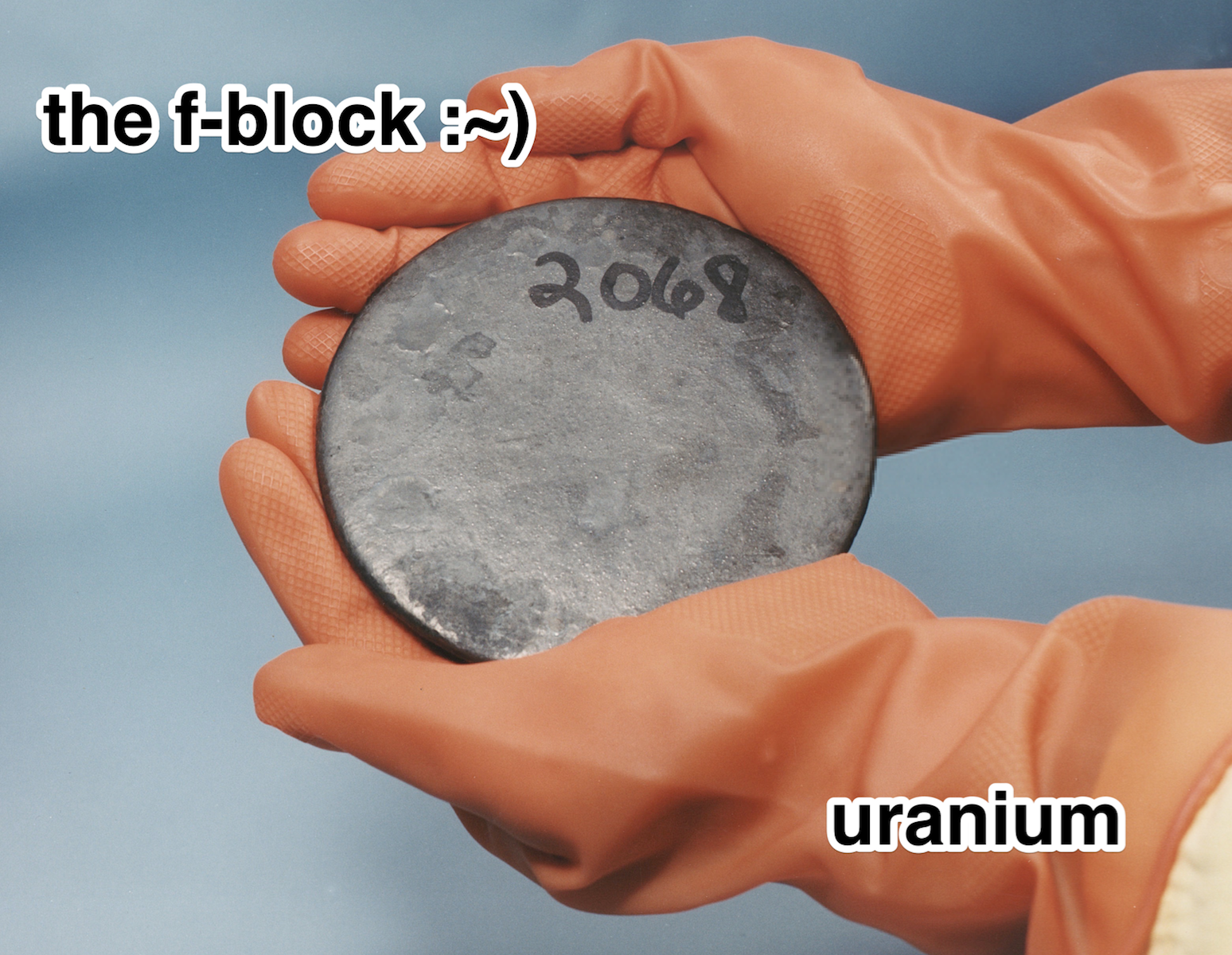

A hunk of enriched uranium [Image credit: US Department of Energy | Public Domain]

Uranium is probably the f-block’s most famous resident, and for good reason — people love explosions.

Uranium is especially well-suited to eruptions. It’s a really big atom: As the 92nd element on the periodic table, it has 92 protons and 92 electrons. It also has either 146, 143 or 142 neutrons, which is a lot. So many, in fact, that uranium atoms have trouble holding onto all of them.

But uranium is rarely found in its pure, unstable form. While a hunk of pure uranium would be a heavy, silvery metal, it’s found most frequently mixed with oxygen in a black crystal called uranite, or pitchblende. Most of the uranium on Earth was made billions of years ago in supernovas, and it’s more common on the planet than silver. People have used it to color glass since the first century AD.

Uranium ore, or Pitchblende [Image credit Geomartin | CC BY-SA 3.0]

What makes uranium special, however, is its instability or radioactivity. The nucleus of the uranium atom decays and dumps some of its weight like a pickup truck full of tennis balls, slowly losing its cargo over the side. That lost cargo is actually in the form of two protons and two neutrons stuck together. When this happens, the nucleus is no longer uranium. The truck drivers change, and uranium switches to thorium.

There are a lot of uses for uranium’s radioactivity. Half of the 146-neutron uranium atoms in a hunk would decay into other atoms every 4.5 billion years or so. Scientists can use this rate of decay to figure out the date of really old things based on how much uranium they have left. For example, this week scientists found the tusk of an ancient elephant-like mammal, and used uranium to determine the fossil was 1.1 million years old. Other scientists have also used uranium dating to determine the date of a significant loss of coral event in the Great Barrier Reef.

Scientists exploit another of uranium’s properties — fission reactions — to power cities or to cause explosions.

Fission reactions are the outcome of splitting the atom. The reaction starts when a neutron is fired at a uranium nucleus, which sucks up the neutron and becomes unstable. The uranium atom then splits into two much smaller nuclei, releasing a lot of energy and setting free more neutrons. If you have a lot of uranium, the neutrons from the first splitting atom will get sucked up by its neighbors, who will also split and release energy, causing a chain reaction until all of the uranium is used up.

That reaction can either be used for good or for evil. If you allow the reaction to happen slowly, you can harness the energy and use it to provide people with electricity. If you allow it to happen too quickly, there will be a runaway chain reaction and an explosion, like the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima. (The bomb dropped on Nagasaki used a different element, plutonium.) This dual purpose is why so many people debate allowing countries like Iran to enrich or prepare uranium for use in reactors. The same hunk of uranium can be used for either the slow, beneficial chain reaction or the quick, exploding one.

![The destruction caused by Little Boy, a uranium bomb, in Hiroshima, Japan [Image credit: US Government | Public Domain]](https://scienceline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/AtomicEffects-Hiroshima-640x502.jpg)

The destruction caused by Little Boy, a uranium bomb, in Hiroshima, Japan [Image credit: US Government | Public Domain]

Uranium can also have negative impacts on the human body. It can cause kidney failure if you eat 50-150mg or about as much as a pill of it. So don’t eat too much uranium, although this amount is far greater than the amount found in food. Also, while a piece of uranium isn’t radioactive enough to cause major bodily harm, people who work in places that process or store lots of uranium, like a nuclear reactor, put themselves at a higher risk for developing cancer later. Of course, it is most dangerous when it is exploding — the energy from a nuclear fission chain reaction could vaporize a person.

Despite uranium’s bad rap, it’s still one of the most important elements, not only in the f-block, but in the entire periodic table. No other element provides 12 percent of the world’s electric power the way uranium fission in nuclear reactors does. Uranium inside the earth even powers the movement of whole continents. With all its uses, uranium is the f-block’s MVP.