The Cascade curtain

Disagreement over using nuclear power in Washington divides the state

Eleanor Cummins • October 11, 2016

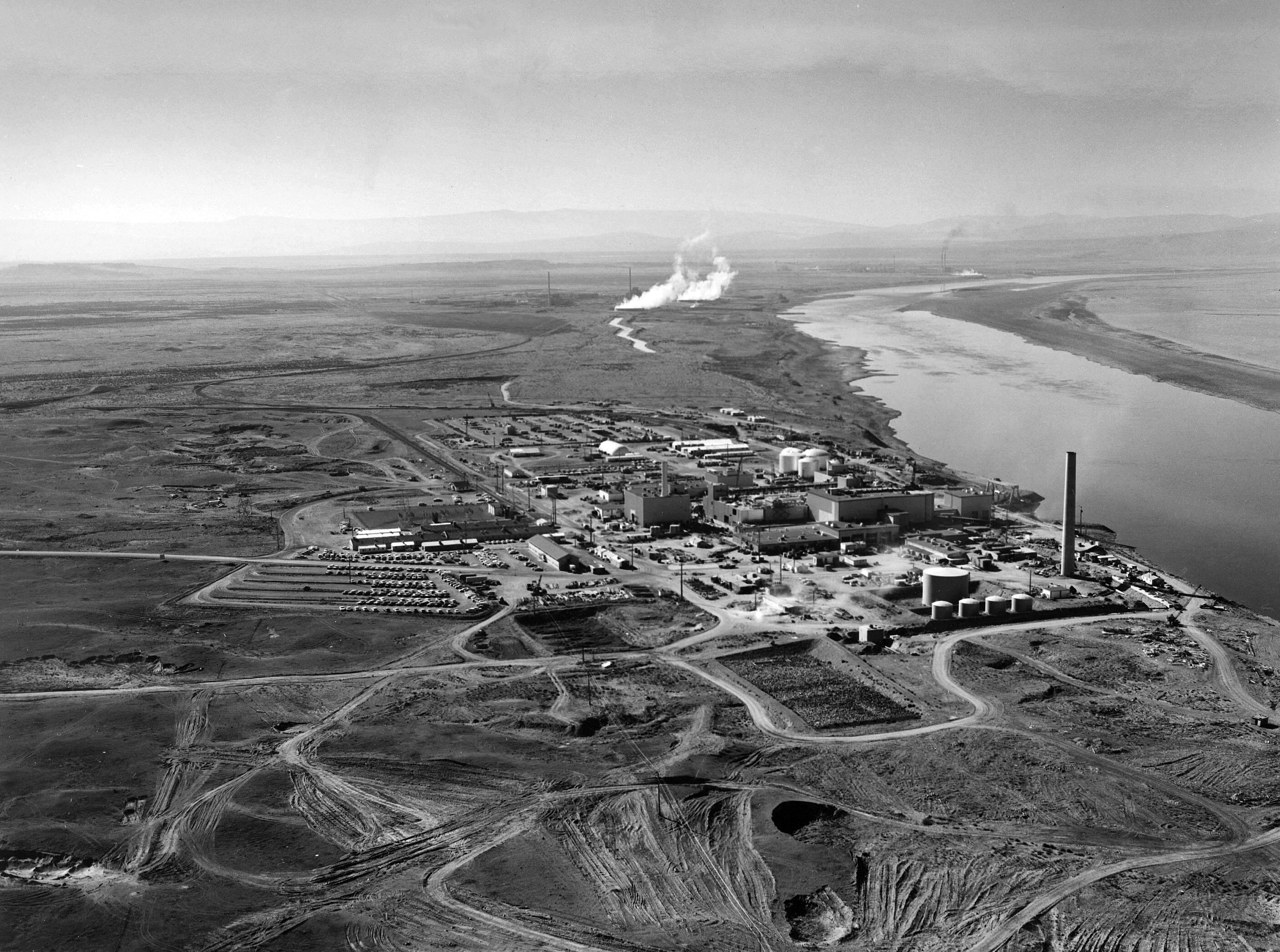

The Hanford Nuclear Reservation produced the plutonium for the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan. Today it produces nine percent of Washington state’s energy. [Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons | CC0]

When my dad first arrived in southeastern Washington state to teach English and talk poetry, he was asked by every new person he met if he had come to work in “the area.”

A skinny, bespectacled Ohioan, it took him a few days to discover that the good people of Richland, Pasco and Kennewick, Washington, collectively known as the Tri-Cities, weren’t just asking if he was working nearby.

“The area,” it turned out, was the Hanford Nuclear Reservation and its peacetime progeny, the Columbia Generating Station.

An hour’s drive up the Columbia River from Richland, Washington, Hanford was the production site for the plutonium that filled up Fat Man, the nuclear bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan. The Columbia Generating Station is a civilian repurposing of the war effort — a nuclear energy plant that produces about nine percent of Washington state’s energy and employs 1,000 people. Growing up near “the area,” I knew few who felt conflicted about the nuclear plant that is the bedrock of their local economy, though people on the other side of the Cascade Mountains, where I went to college, certainly do.

This tension came to a head in the summer of 2016 when the Seattle City Council voted to restrict Seattle utilities from purchasing shares of energy that come from nuclear power, effectively taking the largest urban community in Washington off nuclear power. In its announcement of this unanimous decision, the council also made clear their ultimate hope of shutting down the Columbia Generating Station for good, a plan that has little federal support but some grassroots momentum.

For Tri-Citians like my parents, who live on the dry side of the so-called “Cascade Curtain,” which divides Washington state politically and climatically (through a rain shadow), the Seattle City Council decision seemed foolish. Of course nuclear energy has its challenges, but my mother, for one, thinks Washington should try to rise to the occasion rather than run away. For many Seattleites, from the students I went to school with at the University of Washington to the nine-member city council, the decision was seen as a necessary symbol of the city’s ideological integrity on energy issues. But no matter where you stood, it was clear the decision represented an increasingly relevant fissure in the environmental movement over the role of nuclear power.

Historically, many in the liberal environmental movement have defined themselves in opposition to nuclear energy. Conversations about this power source inevitably turn to the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima in 1945, or the meltdown at Chernobyl in 1986, or even a 2013 Newsweek cover that calls the Hanford plant “America’s Fukushima.” Indeed, when Seattle City Council shared its rationale for shifting away from nuclear energy, it cited first and foremost “health and safety.”

But in a rapidly warming world, some have reconsidered their position. Nuclear power is America’s largest clean energy source, far outpacing solar, wind and other technologies to provide over 60 percent of the nation’s carbon-free energy. President Obama and the United Nations are in agreement on the need to dramatically increase the world’s nuclear energy supply, with the UN calling for a tripling of nuclear power.

As the summer of heated debate progresses to autumn, it’s clear neither side of the Cascade Curtain intends to compromise. Seattle continues its paradoxical efforts to be both carbon- and nuclear-free, and work at “the area” continues apace, with the full support of the Obama administration and a license that guarantees production will continue until 2043.

1 Comment

This story conflates the environmental cleanup work–taking care of five decades worth of wastes from producing Plutonium for defense with a civilian publicly owned nuclear power plant. They are not the same–or even connected, except by the word “nuclear.” The United States has a legal and moral obligation to clean up the ‘mess that won the Cold War.’ The fate of nuclear-generated electricity is–as it should remain-a wholly different question.