Tiny solar flares may explain the sun’s ridiculously hot atmosphere

New evidence suggests tiny solar flares heat the sun's atmosphere to thousands of times the temperature of its surface.

Harrison Tasoff • October 30, 2017

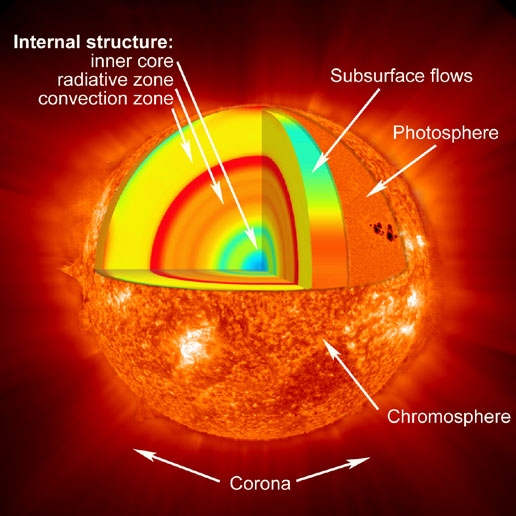

Tiny solar flares may heat the sun’s atmosphere thousands of times the temperature of its surface. [Image credit: NASA | Public Domain]

Small loops of super hot plasma may underlie a mysterious feature of the sun: It’s outer atmosphere, or corona, is far hotter than its visible surface, called the photosphere. NASA recently announced the best evidence so far that nanoflares exist. These solar flares so small they aren’t detectable from Earth. The study results were published Oct. 9 in Nature Astronomy.

“If you’ve got a stove and you take your hand farther away, you don’t expect to feel hotter than when you were close,” coauthor Lindsay Glesener, experiment’s project manager at the University of Minnesota, said in the NASA statement.

The photosphere is a toasty 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 degrees Celsius). However, the corona is regularly 1.8 million to 3.6 million degrees Fahrenheit (1 million to 2 million degrees Celsius), and can even climb to 72 million degrees Fahrenheit (40 million degrees Celsius). The coronal heating problem has confounded scientists for years.

Astrophysicist think that tiny solar flares could be transferring energy from within the sun, through the photosphere, and releasing it as heat in the corona. Since the sun is far hotter than Earth, it’s magnetic field is far more dynamic. The flares, which are coils of plasma, follow the sun’s magnetic field, twisting and snapping as the field changes. This has the potential to transfer immense amounts of energy through the sun’s surface, and discharge it only in the corona. Collectively, these nanoflares could account for the corona’s million degree temperatures, according to the statement.

To test for these nanoflares, scientists launched the FOXSI instrument, short for Focusing Optics X-ray Solar Imager, on a 15-minute flight. The experiment—a collaboration between NASA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), UC Berkeley and University of Minnesota—uses mirrors to detect very faint X-ray signals coming from the sun. These short missions don’t need to be sent into orbit; they just need to make it to space. NASA sends them up on small sounding rockets, and after a few minutes in space, they fall back to Earth, deploy their parachute, and make a soft landing.

A 15-minute flight launched on Dec. 11, 2014 was the second iteration of the FOXSI experiment. Although it only collected six minutes of data, FOXSI achieved its goal. The instrument detected hard X-rays, the most energetic light still within the X-ray range. The presence of hard X-rays suggests the presence of extremely hot material associated with solar flares.

Additional data from the JAXA and NASA Hinode solar observatory, which orbits above Earth in almost continuous daylight, enabled scientists to pinpoint the spot on the sun that these X-rays came from. Since no flares were observed in this region from Earth, the material was likely produced by a series of nanoflares, according to the NASA statement.

“There’s basically no other way for these X-rays to be produced, except by plasma at around 10 million degrees Celsius [18 million degrees Fahrenheit],” said Steve Christe, the project scientist for FOXSI at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “This points to these small energy releases happening all the time, and if they exist, they should be contributing to coronal heating.”

Astrophysicists still want to determine how much energy these nanoflares actually release, and to determine the mechanisms by which they work. For that, Glesener is leading an effort to launch a third FOXSI experiment on a sounding rocket in the summer of 2018. The next iteration will filter out more background noise to allow even more precise measurements.