Microbial world still a frontier, researchers say

At an academic symposium, researchers detailed the barriers and potentials of applying genome sequencing technology to the millions and millions of microbes populating our cities

Marion Renault • November 7, 2018

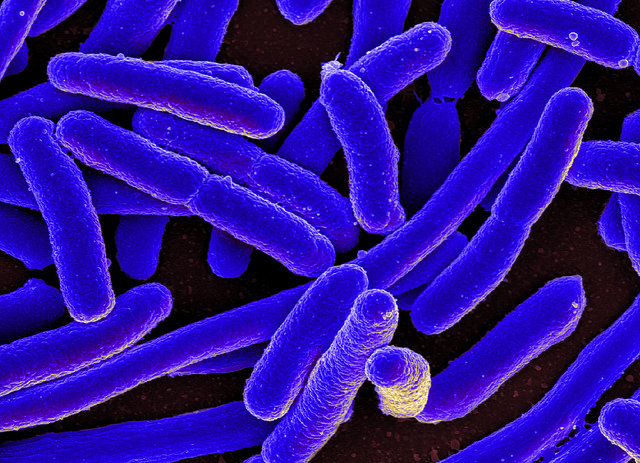

A colorized scanning electron micrograph of Escherichia coli, grown in culture and adhered to a cover slip. Photo courtesy of the National Institutes of Health via Flickr. [CC BY 2.0]

You shake hands with them at the ATM, flush them down the toilet, accompany them on your work commute and kiss them goodnight on your pillowcase.

But researchers are still in the early stages of surveying and understanding the teeming multitude of tiny organisms — bacteria, viruses, fungi and protists — found on every surface and living creature we humans encounter, as well as inside our own bodies.

“We’re just starting to scratch the surface,” said Jane Carlton, director of New York University’s Center for Genomics and Systems Biology, who has studied the microorganisms swarming around the Big Apple’s sewage, soil, pets, cockroaches, ATMs and even bike seats.

Researchers are beginning to harness genome sequencing technology to map and track the microbiomes of everything from sewer rats to water cooling towers, according to presentations made by scientists and public health officials at a one-day symposium, ‘It’s a Brave New World,’ hosted Oct. 12 by NYU and the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Grasping and monitoring the living network of these microbiomes could lead to new methods for tracking infectious disease outbreaks, combating antibiotic resistance and managing urban pests such as bedbugs, rats and cockroaches.

Metagenomics — studying the collective DNA of all the microbes found in environmental samples — has already demonstrated the health risks that come with the sanitized, indoor lifestyle of most Americans, said the University of Chicago’s Jack Gilbert, who studies how humans interact with microbial life.

“Our exposure to the microbial world has been significantly reduced,” he said at the symposium, explaining that while many people may think it’s healthier to seal ourselves off from the messy world of naturally occurring bacteria and viruses, the opposite can be true.

Studies have shown that the Amish — whose “front door is 50 feet from the barn door,” Gilbert said — have lower asthma rates and less aggressive immune responses compared to other farmers who use industrial agricultural techniques and do not live in close proximity to their farms.

One of the key discoveries of metagenomics in recent years is that the array of microbial life varies tremendously from place to place, and over time. Homes and neighborhoods have their own unique microbiome specific to their residents, human or otherwise.

Homes infested with bed bugs or cockroaches, for example, have very different microorganisms than those that aren’t. Knowing this can help researchers understand how those animals produce asthma-triggering allergens and spread pathogens in their feces, according to entomologist Coby Schal of North Carolina State University.

Jason Munshi-South, an urban biologist at Fordham University in New York City, uses genomic sequencing to study another urban pest: Brown rats, also known as Norway rats (though they’re native to China).

He said scientists can use genetic biomarkers to trace the global lineage of urban rats, identify new bacteria and viruses they carry, and even show that rat microbiomes vary from neighborhood to neighborhood.

“This is our unofficial mascot. But surprisingly we don’t know much about the ecology, evolutionary history or microbiomes of rats in New York City,” Munshi-South said.

Another relatively uncharted microbiome central to the lives of New Yorkers is inside the city’s drinking water. New York’s water supply already meets state and federal safety standards, but metagenomics could soon be an important tool to provide early warnings of outbreaks of infectious diseases such as Legionnaires’ disease, a form of pneumonia that can be fatal if untreated, according to microbiologist Brian Raphael of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Someday, in fact, the surveillance tools of metagenomics might be directly available to consumers via handheld devices, according to virologist Jill Taylor of the New York State Department of Health.

“We’re used to [at-home] tests for glucose, but this is coming for infectious diseases,” she said at the symposium. “You’re going to be able to buy this at CVS at some point; this is the world that’s coming.”

Before that happens, though, the field will have to clear some formidable obstacles.

For one thing, sequencing DNA in environmental samples produces a massive amount of data, large swaths of which are unidentifiable because they don’t match anything in the existing databases, said Holly Bik, a microbiologist at the University of California, Riverside.

“We’re basically looking at outer space. The number of stars in the galaxy generally mirrors the number of DNA sequences we’re working with” in any given experiment, Bik said.

In a 2016 sampling of bacterial communities in the biofilm of cooling towers in Pinellas County, Fla., for example, 70 percent of the DNA sequences returned couldn’t be identified because of incomplete reference databases.

What’s more, the microbes on scientists’ skin and in airborne dust can easily contaminate samples, Bik said. And most biologists don’t have the computing skills needed to meaningfully translate genomic data into usable information.

Yet another challenge for scientists looking to map the microbial world: public relations. Genetics and microbes are two topics that often terrify non-scientists, warned Katherine Lyon Daniel, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s associate director for communication.

“If you didn’t know it: Your entire field is worrisome to the public,” Lyon Daniel said. “I think you guys are in a battle for the imagination of the public.”