Sepsis is an overlooked killer in COVID-19 patients. A new tool may help

A new blood-filtering device is getting promising results against sepsis, a condition that affects almost as many people as cancer

Hannah Loss • January 14, 2022

In 2006, the doctors wanted to send him home with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection, but Carl Flatley insisted on staying in the hospital. He knew how quickly things could turn.

Four years earlier, his 23-year-old daughter Erin had died following a routine surgery after her medical team had missed the signs of sepsis — a severe immune response to infection that is surprisingly common, yet frequently overlooked, and kills 270,000 Americans every year.

Now Flatley was worried that he, too, might become one of those casualties. He feared that the doctors were again failing to consider the possibility that his body’s immune system might overreact to the UTI, triggering a potentially deadly case of sepsis.

He was right. He underwent two surgeries to clear the septic infection, spent the next 11 days in the hospital and 40 more days on antibiotics. After seeing what his daughter went through, he was able to recognize the warning signs and advocate for his own care.

“Erin saved my life,” he says.

Flatley, a retired dentist, founded the Sepsis Alliance in 2007 to spread awareness and advocate for patients and families affected by this deadly condition that took his daughter’s life and almost his own. Many have never even heard of sepsis; even Flatley did not understand the risks of sepsis before his daughter’s illness.

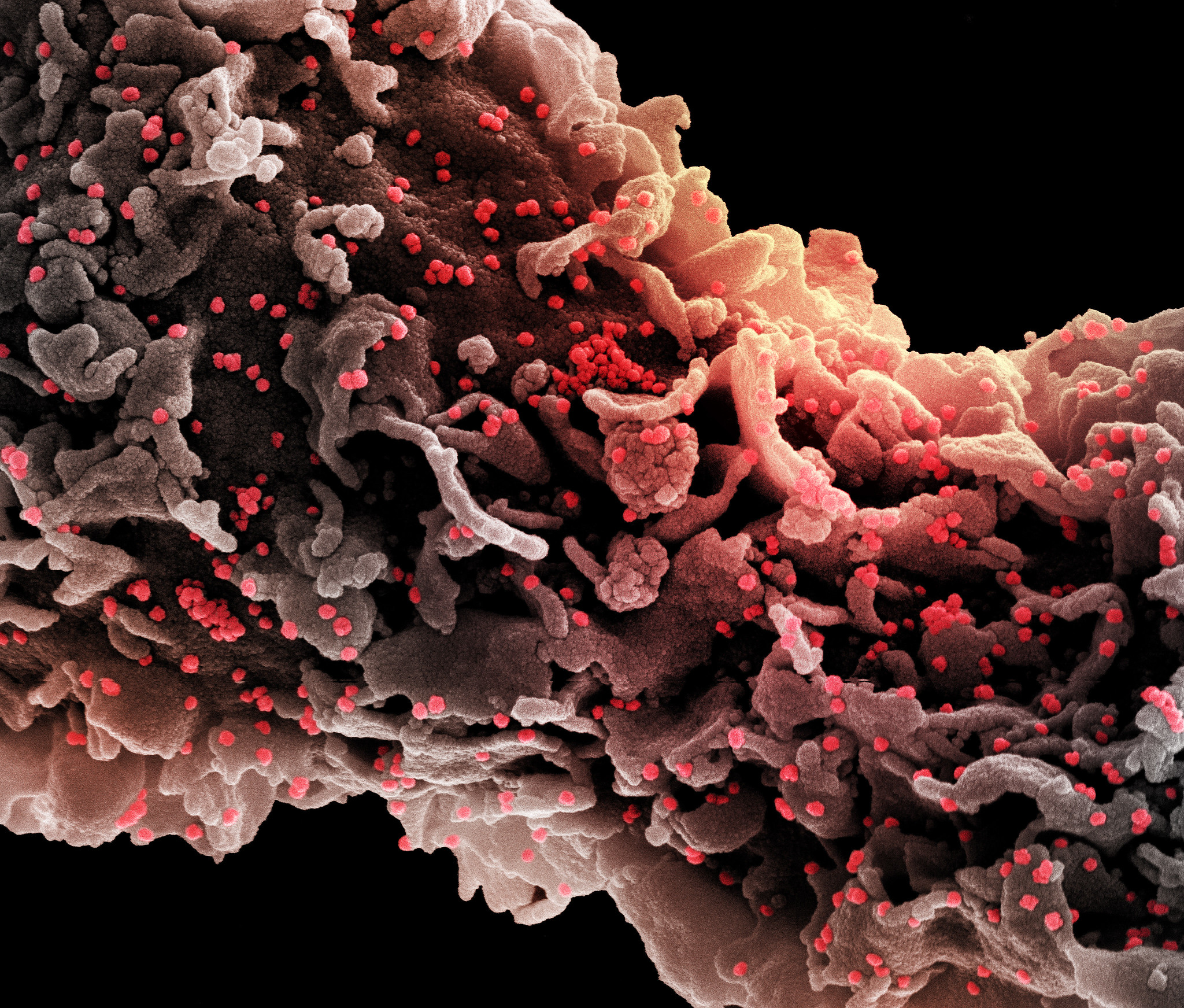

Lately, however, sepsis has been creeping into the national conversation. In October last year, former President Bill Clinton was hospitalized for six days with sepsis. Beyond that, thousands of COVID-19 patients have developed potentially life-threatening viral sepsis, leading the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to grant emergency authorization in April 2020 for an innovative medical device called Seraph 100.

The device, which looks like a thick plastic tube, filters the blood of sepsis patients to remove bacteria, fungi and viruses, including the new coronavirus. In April 2021, the manufacturer, ExThera Medical of Martinez, California, reported promising early results in 53 COVID-19 patients. Over half of the patients using Seraph 100 survived, while only a third survived with typical treatment. The company recently launched an expanded trial in hopes of gaining full FDA approval and then making its filtration system widely available.

“Why would you not try this?” asks Dr. Mink Chawla, a nephrologist and critical care physician who chairs ExThera’s scientific advisory board. He is also chief medical officer at Silver Creek Pharmaceuticals, a San Francisco-based biotech startup.

But sepsis can be a tricky condition to diagnose and treat and some clinicians are not yet sold on the blood filtering device. “We don’t use that here at our hospital. And I’d want to see a lot better data before recommending that,” says Dr. Chanu Rhee, a professor at Harvard Medical School and an epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He notes that several sepsis therapies have been met with initial excitement, including a medical cocktail of vitamins and steroids tested in 2019. Larger studies, however, showed the cocktail was not very effective when compared to existing treatments.

While sepsis is usually not listed as a cause of death in COVID-19 patients, it is often the underlying reason. “Basically, if you die of COVID, you die of sepsis,” says Dr. David Gaieski, an emergency physician who also teaches at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. He explains that the virus causes severe inflammation in people’s lungs and other organs which can lead to septic shock.

Even before the pandemic struck, the need for better diagnosis and treatment of sepsis was urgent, specialists say. Almost as many people are affected by it as they are cancer: 1.7 million Americans per year compared to 1.8 million for cancer, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In fact, sepsis is so common that 1 in 3 Americans who die in a hospital have it. Wounds and urinary tract infections are common sepsis triggers, although it can develop from any type of infection in the body. While most cases originate outside of hospitals, medical procedures like inserting a catheter or an intravenous port can lead to sepsis, too.

For doctors, the challenge of diagnosing sepsis is that it begins with some of the normal symptoms associated with an immune response to infection, including an elevated heart rate, higher white blood cell counts, fever and lower blood pressure — all signs of what clinicians call a “regulated” response to infection.

But in some patients, this immune response can quickly spiral out of control and into “unregulated” territory, explains Gaieski, the Philadelphia emergency room physician. For those patients, natural defenses like fever and inflammation can become harmful. If the infection is not halted through medication, the body can enter septic shock — the most severe form of sepsis with a mortality rate of about 40% among patients in the U.S..

Figuring out which patients are about to enter unregulated sepsis can be extremely difficult, since even those with severe infections might appear to be functioning well: driving themselves to the hospital, for example, and even stopping at Starbucks along the way, says Gaieski. Yet once that person gets to the hospital, they could have a 15% to 20% chance of dying from sepsis, he adds.

Indeed, many of the warning signs are so general that they could be triggered by many activities, including the flu or even intense exercise. “If I do 20 jumping jacks I’ll have a high temperature, my heart rate will be high, I’ll be breathing fast, and raise my heart rate,” says Harvard’s Rhee, noting that these are all potential symptoms of sepsis as well.

As a result, many mild cases of sepsis are not diagnosed before they progress and even severe cases are not always listed as a cause of death on death certificates, says Hou. In fact, the symptoms and severity of sepsis can differ so much that clinicians don’t even fully agree on a common definition for the condition.

The official international definition, which has evolved over 30 years and three international conferences, is that sepsis is characterized by life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by an infection that can lead to septic shock. This is known as the “Sepsis-3” definition.

But doctors in the U.S. use a common checklist that includes a broader definition than Sepsis-3 to determine whether a patient has sepsis. The checklist approach, which is endorsed by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, includes analyzing blood cultures for infection and administering broad-spectrum antibiotics, fluids and medications that raise blood pressure. This approach can help: a study published in August 2021 found that compliance with these steps reduced the 30-day risk of mortality in septic patients by 5.67% and also shortened their hospital stays.

The checklist approach, however, has created a confusing situation. The list, which has been in place for twenty years, classifies many signs of infection as sepsis. The newer Sepsis-3 definition, on the other hand, is more specific: It applies only after an organ is affected. “You can see why if you’re a clinician you’re confused about this,” Harvard’s Rhee says of the dueling definitions. “When I give lectures and talks to the [medical] residents they’re like, ‘What is going on here?’”

The disagreement is about more than just nomenclature. Rhee favors the Sepsis-3 definition because he believes that when the term “sepsis” is applied too broadly it can impede clinicians from homing in on which patients need urgent and aggressive medical care. Other physicians, however, argue that calling even milder cases “sepsis” is actually a very helpful way to increase awareness among patients and prompt doctors to intervene earlier before an infection grows out of control.

Patient education about early signs of infection is crucial to save lives, argues Dr. Cindy Hou, an infectious disease specialist at Jefferson Health in New Jersey who is a board member of the Sepsis Alliance. She encourages providers to have conversations with patients about warning signs, especially if the patient is at higher risk of developing sepsis because they are very old or young, undergoing kidney dialysis or have an underlying immune condition. Those warning signs, she says, include fever, confusion, shortness of breath and pain.

Public awareness of COVID-19, including the need to monitor symptoms and check blood oxygen levels at home with pulse oximeters, has also helped increase awareness of sepsis, according to Hou. People are learning how to spot early signs of infection.

When a serious case of sepsis arises, clinicians have to respond immediately. Tests need to be quick and comprehensive to tease out if someone has an infection from a virus, bacterium or fungus so that they receive the right medicines. There have been major improvements on this front in recent years, with turnaround times for blood cultures and other screening tests reduced to a few hours instead of several days, according to Rhee.

Some hospitals are also experimenting with software that uses artificial intelligence to scan patient charts and send alerts to physicians whose patients may be septic and in need of immediate testing and treatment, Hou says.

However, progress on treating sepsis, as opposed to diagnosing it, has advanced more slowly — until recently, at least.

There are some newer antibiotics to help treat multidrug-resistant infections. But they are often very strong medicines that must be administered intravenously, which requires hospitalization and increases risk for another potential infection at the IV site. In 2019, a new drug cocktail composed of Vitamin C, thiamine (Vitamin B1) and steroids was investigated as a therapy for sepsis patients. But it turned out not to improve outcomes more than existing treatments.

ExThera Medical’s new filtration device, Seraph 100, takes a different approach. It works by removing all physical traces of a pathogen from a patient’s blood, which can help reduce overall inflammatory response. It’s even more effective when combined with antibiotic treatment, according to Chawla, the ExThera Medical science advisor.

The company’s initial tests in early 2021 showed that of the 53 COVID-19 patients whose blood was filtered, 34 survived the infection or about 62% of all participants. By contrast, in the group of 46 patients whose blood was not filtered by Seraph 100, only 15 survived or about 32%. Patients usually need about two filters over two days, costing $1,500 per day, which is far less than the total cost of a hospital stay for a sepsis patient — ranging from $16,000 to $40,000. The results are promising, says Gaieski, the emergency care physician. But he wants to see more data before endorsing the device’s effectiveness.

In late 2021, ExThera scaled up its testing at 15 U.S. community and military hospitals for patients in septic shock, including non-COVID-19 patients. Chawla hopes that if the results are favorable, the Seraph 100 may get full approval from the FDA. The device is already approved in Europe for use in sepsis patients with a variety of infections, not just COVID-19.

The pandemic surge in viral infections has only increased the urgency of educating the public and healthcare providers about sepsis, says Sepsis Alliance’s Carl Flatley. But he also says there has been huge progress since the alliance began urging clinicians to use the checklist to catch early warning signs. “We’ve assembled so many bright people that are making a difference,” Flatley says. “It’s incredible. I’m so proud.”

4 Comments

We have had a couple family members impacted by sepsis in the last year. We were introduced to the term silent UTI. We were like what was that. It is real and exceptionally dangerous. Thank you for the great article !!

Sepsis is an overlooked killer in COVID-19 patients because infections (viral, bacterial, fungal) are not being differentially diagnosed and treated.

For example, Antibiotics and steroids are contraindicated for fungal infection. If broad spectrum antibiotic is given to a patient with misdiagnosed or unknown chronic fungal infection (i.e. urinary tract infection or tinea pedis) the fungus will get worse leading to organ failure and death.

We as a society must demand research and funds for differential diagnose tools/tests for infections in ER and treatment of various types of infections.

A friend just died from sepsis with Covid in a local Wisconsin hospital. She was 50. They disconnected her life support. In contrast my father-in-law age 92 had sepsis in New Jersey and survived. My concern now is whether ALL hospitals are aware of treatment options and proper diagnostic procedures. I can tell you from my experiences with this Wisconsin hospital that they lack in diagnosis of a disease that nearly killed my son, not once but twice. How do we investigate whether the hospital we rely on has the knowledge and capabilities to treat people.

Terrifying. I had a brush with sepsis this past year after a UTI https://www.premiermedicalhv.com/divisions/services/urinary-tract-infection-uti/ went wrong. I’ll never take UTIs lightly again. It was so scary and I ended up with a huge bill. Didn’t even know what sepsis was before my scare!