Munching on plastic?

Microplastics are everywhere — including in our bodies. Here is what you need to know

Dawn Attride • January 10, 2024

Macroplastics break down into microplastics that further break down into nanoplastics. Credit: FLY:D | CC0 1.0

Plastic has invaded every inch of our lives — and seemingly every cell in our bodies.

Researchers have found tiny grains of plastic in everything, from salt to seafood. Experts say there are reasons to worry, even if research of the health effects in humans is only just emerging.

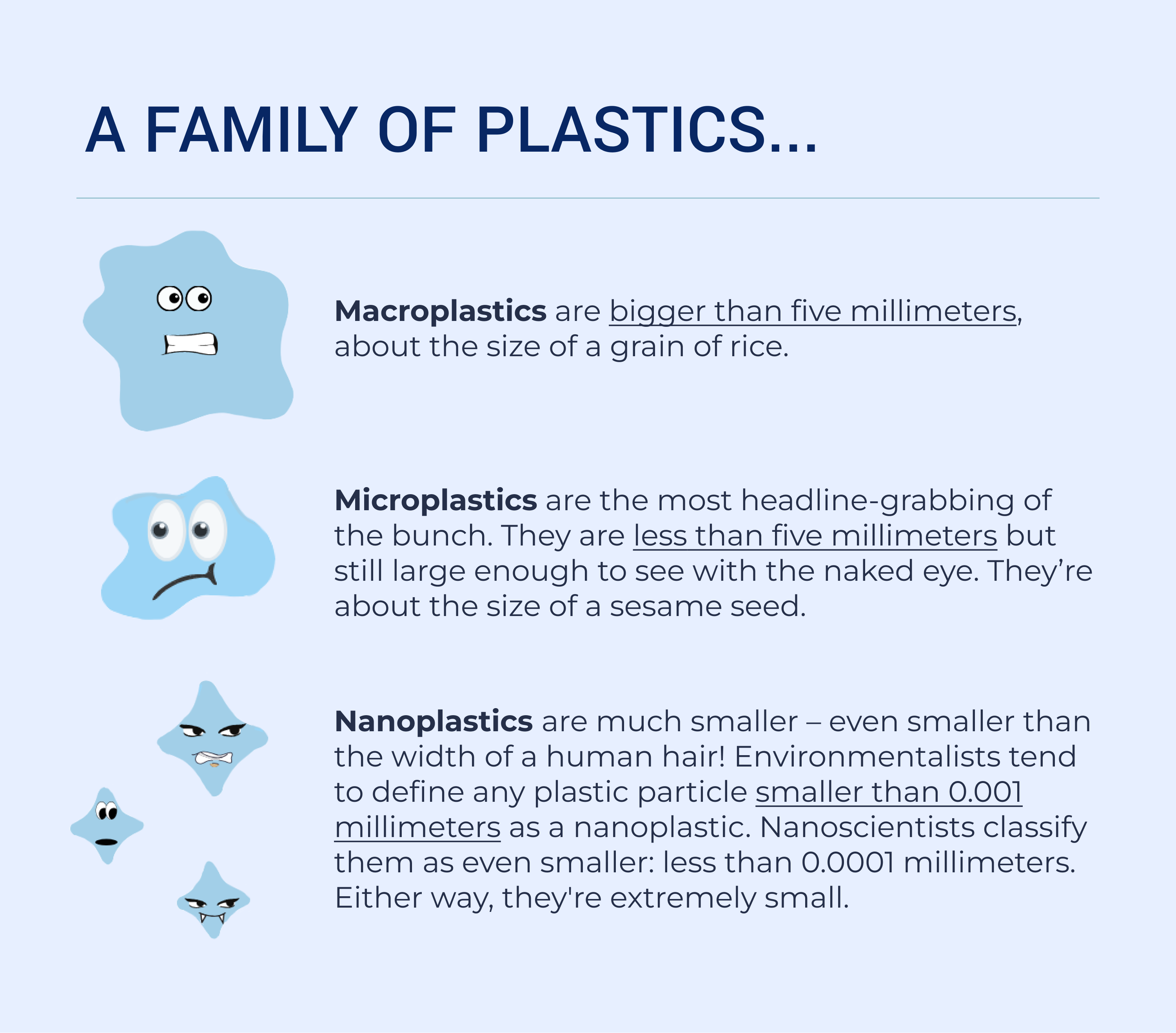

In this case, size matters. Scientists studying the effect of plastics on health divide plastics into three categories: macroplastics, microplastics and nanoplastics. While larger plastic particles are more likely to be excreted, smaller nanoplastics can persist and move throughout the body, creating hidden health risks from their chemical additives.

Food, air and packaging are the main ways we are exposed to plastic. Each route poses different potential risks, depending in part on the size of the plastic particles involved. So, could we be munching on plastic? Let’s find out.

Plastic particles can be divided into three broad categories of size. Some are capable of more mischief than others [Credit: Dawn Attride and Gayoung Lee]

In Food

Consider seafood. When we think of plastic pollution, what often comes to mind are heart-wrenching images of fish tangled in plastic wrappers. The bigger concern, though, is what those fish ingest — and what we ingest by eating them.

Filter feeders, or marine organisms that filter in whatever food sources are around them — algae, plankton or tiny beads of plastic — have the highest consumption of plastic. When we eat filter feeders, such as mussels and clams, we also consume the plastic inside them. “Normally, you would just eat the filet of a fish, for instance. With mussels, we are eating the whole mussel, microplastics and all,” explained Alice Horton, a marine researcher at the U.K. National Oceanography Centre.

Ingesting microplastics spells bad news for sea creatures’ life cycles; mussels exposed to polyester microfibers were much smaller and grew 36% slower than unexposed mussels in a 2023 study. Exposure to more natural fibers like cotton did not show the same concerning result.

When microplastics are ingested through food and water, they can pass through the intestine and enter the bloodstream according to a Dutch study in 2022. A 2017 study in fish showed that consumed nanoplastics traveled to their brain, causing the fish to become disoriented, slowing their eating and even stopping their schooling behavior. This movement from the bloodstream to major organs isn’t exclusive to fish: A team of Italian researchers found 12 nanoplastic fragments in four human placentae — though the exact health implications are still unknown. Some research suggests ultrafine nanoplastics might also enter the bloodstream from the lungs, although this route is less studied.

In the Air

Airborne exposure to nanoplastics may be a larger risk — according to Horton, we might even “consume more plastics from air particles that land on the mussels than the plastics already in them.”

We ingest more plastic from inhaling fibers in our homes than from our food sources, according to a recent study in the journal Environmental Pollution. Not only that, microplastic can also enter our lungs via synthetic fibers in clothing, rubber tires and landfills.

“Chemicals can attach to plastics in landfills or incineration facilities, and can be cancer-causing when ingested,” explained Phoebe Stapleton, a toxicologist at Rutgers University.

The hydrocarbon chains that makeup plastic have a large surface and a static charge that can attract potentially toxic molecules such as aluminum, lead and copper. When harmful molecules attach, suddenly this piece of plastic “becomes a Trojan horse,” said John Boland, a nanochemist at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland.

The evidence points to plastic-induced inflammation as a health risk. Inhaled nanoplastics interfere with the lungs’ immune defense, according to a 2023 study. Our lungs produce mucus and recruit immune cells to clear the plastics, but this doesn’t always work: microplastics as big as 0.25 mm have been found deep in lung tissue. When the amount of immune cells exceeds 6% of total lung volume, it results in an “overload paradigm,” a situation in which immune defenses may lose their ability to fully clear plastics from the lung.

This creates chronic inflammation due to immune cell build-up in the lung tissue; inflammation can, in turn, lead to cancer. For instance, workers who manufacture vinyl chloride, a key feedstock used to make many plastic products, are 20% more likely to develop lung cancer for each additional year of work.

In Packaging

Food packaging is also a key player in plastic consumption. Those of us who drink bottled water consume an average of 325 plastic particles per liter, compared to 5.5 plastic particles per liter of tap water. “If an individual is eating more processed foods or bottled water, that increases the likelihood of [microplastic] consumption,” Stapleton said.

Preparing food can generate microplastics, too. Heating breast milk in a single polypropylene plastic bottle can release up to 55 million particles, according to a study by Boland’s research team. Even plastic kettles have come under scrutiny: microplastic particles accumulate in their bases, adding tiny amounts of plastic to your tea as you pour. Over time, the inside of the kettle may turn brown —– but that’s actually a good thing. “That color is copper oxide, and it’s a sign that your kettle isn’t releasing microplastics anymore,” Boland said.

What Happens Next

Plastics are hydrophobic: they do not mix well with water, which is why ingested plastic particles — especially the smallest nanoplastics — can aggregate in proteins and fats in the body. “It is now surrounded by all this bio stuff, and it can get into membranes and go places where it shouldn’t really go,” Boland said.

This is a problem because plastic may also affect our hormonal systems. Consider the plasticizer Bisphenol A (BPA), used in containers and some store receipts. Studies have shown that human cells respond to BPA as if it is an estrogenic hormone, potentially increasing the risk of ovarian and breast cancer.

What you can do

As researchers keep working on understanding the health effects of microplastics, there are some simple steps consumers can take to reduce their exposure. Stapleton recommends choosing cotton over polyester and glass over plastic containers. Other recommendations include choosing metal appliances instead of plastic, eating less shellfish and, perhaps most importantly, improving ventilation in the places where we spend the most time.

1 Comment

Love this article and topic. Please take a look at biodegradable PHA and Danimer Scientific. While it won’t help with the damage already done it will help in the cleanup.