FDA rules mean women now know their breast density after mammograms — but is it enough?

Experts praise the FDA’s implementation of breast density notifications, but say more should be done for breast cancer risk

K.R. Callaway • January 24, 2025

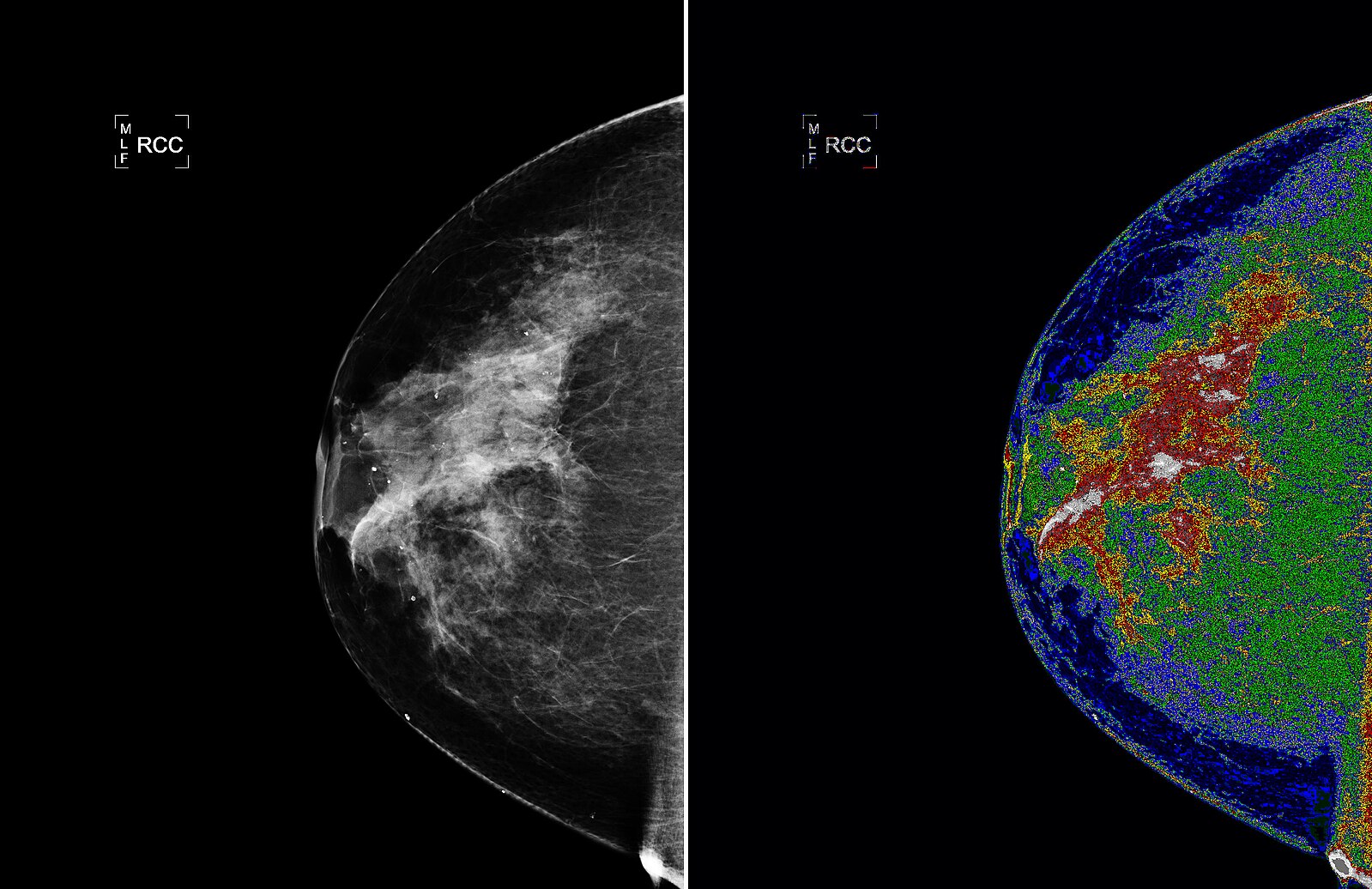

Understanding one’s breast cancer risk can be complicated — especially for women with dense breasts. FDA rules may help women understand how their breast density can impact their annual mammogram and their cancer risk. [Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center]

As a healthy, active 46-year-old who had no family history of breast cancer and was diligent about getting routine mammograms, Amy Charney had no reason to expect she would be diagnosed with breast cancer.

After noticing a small but “alarming” lump under the skin on her right breast in November 2014, Charney moved up the date of her annual mammogram but thought, “Of course that’s not cancer.” Charney’s radiologist agreed everything looked fine on the mammogram but suggested further screening to make sure the lump was nothing to worry about.

Further screening revealed that Charney had nine centimeters of an early stage, slow-growing cancer called ductal carcinoma in situ, as well as a secondary tumor that was “smaller, but more worrisome” because it had invaded healthy tissue.

“I went on to have chemotherapy, and 10 years later, I’m doing well,” said Charney, who is now a development engagement manager at the Susan G. Komen Foundation. “But the point is that there was nine centimeters of cancer that they didn’t see on my mammogram.”

How could this have happened? Charney’s extremely dense breast tissue had the potential to both increase cancer risk and make it harder for radiologists to identify her cancer on a mammogram.

Last September, the Food and Drug Administration announced it would begin enforcing an amendment to the Mammogram Quality Standards Act of 1994, which requires mammography reports to include information about breast density. Between 40 and 50% of women have dense breasts, which can increase breast cancer risk and can make cancer harder to detect without additional screening — although it is unclear whether additional imaging consistently improves cancer detection.

Researchers and activists praise the FDA’s move, but many would like to see more done to make information about breast cancer risk and options for additional screening more accessible.

“This is something we fought for a long time,” said Krissa Smith, vice president of education at the Susan G. Komen Foundation, which has advocated for this change for over a decade. “Knowledge is power, and we are thrilled that patients have more of that at their fingertips.”

Notifying women of their breast density is not a new concept. About half the country — including North Carolina, where Charney received her breast cancer diagnosis — was already issuing breast density notifications after mammograms, estimated Laura Heacock, a professor of radiology at New York University Langone Health.

However, prior to the recent implementation of this FDA amendment, whether patients received a notification after their mammogram — and the information included in that notification — varied by state.

“Consistent national breast density reporting requirements are critical in order to ensure that breast density reporting occurs in all states, and that patients and health care providers receive accurate, complete, and understandable breast density information,” an FDA spokesperson said.

This information comes in the form of reports sharing whether breasts are not dense, have scattered areas of density, are uniformly dense or are extremely dense. These reports help to address a problem Smith said caused confusion among mammogram patients prior to the amendment. For many years, women either didn’t know they needed additional screening or were not told why additional screening was necessary.

Breast tissue is considered dense when there is more functional tissue, like milk ducts and mammary glands, than fat. Dense breasts are more common in women who have not yet gone through menopause, according to Smith.

Unlike fat, which is transparent on a mammogram image, functional breast tissue shows up as white masses — just like cancer, making them difficult to distinguish.

“[Breast tissue] patterns can be very different from woman to woman, almost like a fingerprint,” Heacock said. “So when we’re asking to look at your old mammograms … that’s because we want to see the pattern of your breast tissue over time. Cancer tends to show up as a difference in that tissue pattern.”

Breast density is not something you can identify from a self-exam or even a clinical exam. Only an imaging test, like a mammogram or a magnetic resonance image, can determine breast density, according to Smith, so clear communication about breast density is important.

But that’s not enough, said Smith.

“Right now, they just tell you, ‘You have dense breasts,’” she said. “Well, what does that mean? Do you need to do anything with that? And so that’s where we still have work to do.”

Dense breast tissue can make breast cancer four to five times more likely, Smith said, citing a 2000 study. A 2022 study estimates dense breasts more than double the risk of cancer, with a 6.2% risk for women with the lowest category of breast density and a 14.7% risk for women with the highest density.

It’s not entirely clear why dense breasts are linked to higher risk, according to a spokesperson of the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. One possibility is having more glandular tissue — as people with dense breasts do — may provide more opportunity for abnormal cell growth, the BCRF spokesperson said.

Currently there are no guidelines about what type of additional screening patients with dense breast tissue should receive — in part, Heacock said, because there is no one method of screening that is ideal for every patient.

“I think [the FDA] tried to leave [the notifications] open ended so that people can have these discussions with their primary care provider,” Heacock said. “They don’t have hard and fast recommendations [for additional screening] because, at the end of the day, it comes down to a patient and a doctor making that decision together.”

Still, the lack of guidelines can make the process of getting additional screening confusing, according to Smith.

Doctors may recommend whole breast ultrasounds and breast MRIs, which are more sensitive than standard mammograms. But the sensitivity of these tests make false positives — which occur when areas of concern are identified despite no cancer being present — up to 60% more likely, meaning women with dense breasts are more likely to have to undergo further screening tests and biopsies, prolonging uncertainty about whether they have cancer.

The BCRF spokesperson says that researchers are “actively working to develop new screening methods that detect cancer as early as possible while reducing false positive rates.”

Additional screening is also not always covered by insurance — even when the initial mammogram was covered and the same doctor ordered the additional screening.

“I find the most frustrating situation is when we’re recommending something, but a patient informs me that their insurance doesn’t cover it,” Heacock said.

Charney, who is now cancer-free after a mastectomy and chemotherapy, undergoes additional diagnostic screening each year due to her dense breast tissue and to ensure her cancer hasn’t returned. Insurance helps cover the cost of her annual diagnostic mammogram and breast MRI, but Charney said she still often pays high out-of-pocket costs. And Charney says she is one of the “fortunate” ones who doesn’t have to choose between paying for tests or bills.

“Part of the reason it’s so frustrating is I think it would be way more expensive for my insurance company to cover cancer treatment than it would be to pay for this [screening],” Charney said. “It could be cost prohibitive for people, which could lead to people dying from the disease.”

Although the new breast density notification guidelines come from the FDA, the FDA is not the federal department in charge of determining what additional screening tests insurance — including Medicaid and Medicare — cover for people with dense breasts, according to Smith. Instead, this falls to the United States Preventive Services Task Force, which decides which preventative services insurance companies must cover without requiring a copay from patients.

The lack of guidelines about what should qualify as a preventative secondary screening for women with dense breasts presents a barrier to insurance companies covering these screening measures, Smith said.

Even in countries with socialized medical systems, additional screening for women with dense breast tissue is not guaranteed.

“The U.K. stance at the moment is that we don’t inform women of their breast density,” said Fleur Kilburn-Toppin, a breast radiologist at Cambridge University Hospital in England. “When they go for screening mammography, they simply get either a letter saying it’s all normal, or they get a letter saying they need to be recalled for further tests.”

Kilburn-Toppin says there are a number of groups in the U.K. that advocate for the NHS notifying women of their breast density, but she sees two major reasons why these notifications have not been implemented.

Firstly, it is unclear whether knowing breast density and getting additional imaging will make a difference in cancer detection. Secondly, the U.K. does not currently offer additional imaging, like some other countries such as Austria do. “It’s probably felt that telling women their breast density without having any solution to that might not be that helpful,” Kilburn-Toppin said.

“Screening is always a balance of benefits and harms,” Kilburn-Toppin said. “Benefits being you diagnose cancer, and harms being things such as over-diagnosis, whereby you diagnose women with a cancer that you have to treat but wouldn’t have caused harm within their lifetime. But there’s also other side effects of screening, such as anxiety and obviously financial costs.”

One solution Kilburn-Toppin says she hopes will become the norm in the U.K. is risk-based breast cancer screening, which means screening practices — like determining what additional screening, if any, to offer — are adapted to the risk level of the person being treated.

A woman is more likely to get breast cancer if she is older, smokes, or is overweight, among other factors, according to Kilburn-Toppin. Factors like hormones, BMI, race, genetics, and family history — like whether other women in your family have dense breasts — also play a role. However, only a very small percentage of women are at a high risk of developing breast cancer, Kilburn-Toppin says.

Ten years after her breast cancer diagnosis, Charney agrees that the FDA’s newly-implemented regulations are “moving in the right direction.” Even so, she encourages women to be aware of risk factors like breast density and to keep advocating for themselves if something doesn’t feel right — even if everything looks fine on their routine mammogram.

“Breast cancer can happen to anybody,” Charney said. “Be your own advocate and continue to ask questions … you know your own body the best.”