Choppy waters lay ahead for U.S. fisheries

Proposed changes to the Magnuson-Stevens Act, our nation’s fishery management law, would compound problems for the nation’s fish

Harrison Tasoff • May 31, 2017

Cod populations abruptly plummeted in the early 1990s due to decades of overfishing in New England and Newfoundland. They are slowly beginning to recover [Image Credit: modified from August Linnman via Wikimedia | CC BY-SA 2.0]

I know fish like most people know celebrities. And I know celebrities like most people know fish.

My eyes light up when I spot a wolf eel, holed up in a stony crevice like an old hermit. I know the small characteristics that distinguish sardines from anchovies (anchovies can scissor their tails), and I study their relationships like an amateur genealogist. And although I still can’t tell a blue-fin tuna from a yellow-fin, I take consolation that the staff at the Monterey Bay Aquarium often have trouble with this too.

I’m basically a birder but for fish.

I also enjoy fish on my plate — a peculiar arrangement considering what I’ve just said — but I recognize their nutritional value and realize they are much more sustainable than the livestock we raise on some 68,000 square miles of corn in the United States.

Nevertheless, I don’t fish, I don’t dive, and I get seasick on boats. I even got seasick while snorkeling. To say I have an interesting relationship with fish is putting it mildly.

In my case, a quick bit of self-analysis will actually give you a fairly accurate account of my interest in fish. I grew up around aquaria, tidepools and an older brother who’s been studying marine biology since I was in diapers.

As I’ve written about this topic so dear to my heart, I’ve learned more about how the U.S. keeps fish populations, or stocks as fishermen call them, stable. But I’m not the first person who’s become worried about our ability to successfully maintain fish populations.

Even fish get caught in the cross-hairs of caustic partisan politics. Laissez-faire management strategies are gaining political appeal, despite broad support for the current fishing regulations, which combine community and industry input with rigorous scientific analysis. Congressional bill H.R 200 — a modification of the longstanding Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act — is the latest incarnation of this trend.

Right now, the country’s fisheries are managed by eight regional councils under the National Marine Fisheries Service, also known as NOAA Fisheries. The system was set up in 1976, when President Gerald Ford signed the Magnuson-Stevens Act into law.

Over the last 40 years, the measure has enjoyed wide support. “It’s become one of the best, if not the best, fisheries management tools in the world,” says Steve Scheiblauer, who serves on the advisory committee Pacific Fishery Management Council and had been a harbor master in central California for 40 years.

Part of Magnuson’s success comes from the regional councils, which themselves have advisory subgroups composed of a variety of stakeholders and include environmentalists, scientists, fisherman and Native Americans. “I think it’s the best public policy arena I’ve ever seen,” says John Holloway, who represents fishermen on one of the advisory committees to the Pacific Council.

“One of the other things that the Magnuson-Stevens Act embraces is the principal of adaptive management,” explains Scheiblauer. “So when mistakes are recognized, there’s a method to correct them.”

Fishery management got a significant boost when the act was reauthorized in 2007. The new legislation required the councils to base their strategies and quotas on scientific population surveys.

It is crucial that these fish surveys are done by marine biologists. Professional fishermen’s knowledge of fish runs as deep as some of the waters they trawl. But their background prepares them for different kinds of tasks than a marine biologist, whose years of training equip them with the skills to conduct surveys and model ecological phenomena.

Both fish and fishermen benefit from the role of science in fishery management: Last year NOAA Fisheries announced that nearly 40 fish stocks had recovered since 2000.

The 2007 reauthorization also strengthened the timeframe that the agencies have to rebuild depleted fish stocks. When managers discover that a stock is overfished, the regional council sets out a plan to rebuild the population in the shortest time possible, which is no more than 10 years for most fish species.

This timeframe is necessary to keep federal agencies from simply kicking the can down the road when it comes to overfishing. And a shorter timeframe allows for more fishing opportunities sooner, rather than dragging restrictions out, according to Ted Morton, the Director of U.S. Oceans at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

But most fishermen would like to see these timeframes loosened. The restrictions are a big problem in mixed fisheries, where several species associate with one another. Cod, haddock, and pollock — several related fish that live at similar depths along the East Coast — are one example of a mixed fishery.

The restrictions sometimes force fishermen to limit or forgo their catch of a species with a healthy population if it interferes with the recovery of a struggling stock. It’s nearly impossible to catch dover sole, for example, without catching some overfished black cod, Scheiblauer says, since the two fish associate with each other.

Morton says that extending the timeline would not resolve this issue, but fishermen like David Crabbe in Monterey, California disagree. A longer recovery time means population targets don’t have to be met quite so quickly, which would allow fishermen to catch just a few more of the recovering fish over the course of a season. This, in turn, would enable them to catch significantly more of the plentiful fish they are actually targeting.

“Tweaks in the regulation might help alleviate the constraints some,” says Crabbe, who despite his name, actually catches squid and forage fish like sardines and mackerel.

But the bill currently in the House doesn’t just lengthen rebuilding timeframes, it explicitly exempts the councils from setting catch limits for forage fish. In addition to their commercial value, forage fish serve as the primary food-stuff for larger fish like tuna, snapper, and cod. Rolling back management on forage fish could have resounding consequences for these fisheries.

“I’m not aware of any kind of rationale for why this is in [the bill],” says Morton at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The yelloweye rockfish population in the Pacific Northwest straddles the U.S.-Canadian border, with only a small portion under U.S. jurisdiction. Many fishermen argue that this falsely deflates stock assessments, and restricts their fishing opportunities. [Image credit: Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife via Wikimedia | CC BY-SA 2.0]

H.R. 200 would even give the revised Magnuson-Stevens Act priority over the Endangered Species Act, which NOAA Fisheries also administers along with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This means that when the two laws intersect, Congress would require NOAA to manage the situation as a commercial, rather than environmental, issue.

While the Endangered Species Act has been the topic of much debate itself, a quick look at its track record shows that it does prevent extinction and promote recovery. The law is currently protecting my favorite rockfish (the long-lived bocaccio) up in the Puget Sound as well as populations of species with more recognizable commercial histories, like salmon and steelhead.

Giving priority to the Magnuson-Stevens Act when the two butt heads will undermine the strength and efficacy of the Endangered Species Act, which is continually under attack.

Despite its strengths and popularity, the Magnuson-Stevens Act is not equipped to address such a diversity of issues, nor was it intended to. Giving preference to Magnuson erodes the comprehensive monitoring that these issues deserve.

To be effective, the new bill would need “very carefully nuanced language to make sure that it cannot be abused,” warns former harbormaster Scheiblauer. But H.R. 200 is not nuanced, and its provisions are not new.

This is the third Congress in a row that has introduced a similar bill, says Morton at Pew. Although the last two versions were unsuccessful, the second one made it through the House of Representatives in 2015. It died in the Senate, which has been less convinced than the House that Magnuson-Stevens needs a major overhaul.

Unlike the previous two reauthorizations, which had broad support, votes for the 2015 bill came almost exclusively from Republicans. This is troubling for a law that has long enjoyed wide-ranging support from industry, scientists and conservationists alike.

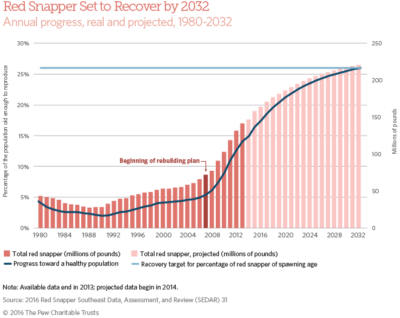

The growth of the red snapper population along the Gulf Coast has kept pace almost perfectly with NOAA Fisheries’ goal of a full recovery by 2032. [Image credit: The Pew Charitable Trusts]

But organizational problems turn what is a good situation overall into a headache for recreational fishermen, according to Mike Gravitz, the director of policy and legislation at the Marine Conservation Institute.

Even though red snapper populations have grown significantly, the fishing season and bag limit —how many fish a fisherman can keep — has actually gone down, says Gravitz. “And this just pisses people off.”

But this isn’t a problem with the Magnuson-Stevens Act, it’s a consequence of a recovering stock.

“The problem is the fish they do catch and are allowed to keep are getting bigger,” says Gravitz, which means that fishermen reach their weight-limit more quickly than before. Particularly recreational fishermen, who can’t coordinate in the way that commercial fishermen can. And although catching fewer, bigger fish is still exciting, it means fewer adventures, and fewer boat and gear rentals overall.

But older, bigger fish have more offspring than smaller fish, which means recovery should start speeding up. As the stock returns to a healthy size, the restrictions will be phased out.

Overall, though, support for the Magnuson-Stevens remains high. “The Federal process [for fishery regulation] in the US is the best I’ve ever seen in terms of” its provisions for stakeholder involvement and input, says Holloway, who is a recreational fisherman himself.

Fisherman David Crabbe concurs. “I think that it strengths are that it’s a transparent public process … [with] a broad range of opportunities for the public to weigh in.”

The broad support for the Magnuson-Stevens Act is a rarity in the regulatory world these days, and something to celebrate. What we need now is to embrace Magnuson’s strengths – like its diverse advisory councils – which address changes and frustrations as they arise rather than overhaul a law that’s doing its job.

Fish are often out of mind for land-lubbers in a way that birds, game, and livestock are not. It’s hard to have a connection with animals you rarely see outside of a market. That’s why we need smart regulations like Magnuson to manage them: for the fish and their ecosystems, for fishermen and seafood eaters, and for crazy fish-guys like me.

1 Comment

What is NEVER mentioned when statements that portray fishermen as greedy, fish killing, ocean rapist like this are made-“Cod populations abruptly plummeted in the early 1990s due to decades of overfishing in New England” is this:

The US government created the over fishing of the 80’s and 90’s with the Capital Construction Fund which significantly and artificially over capitalized the fishing industry, ESPECIALLY in New England. Most of the people writing this propaganda and managing the fisheries were not even there, yet they have absolute opinions and expertise.

As long as you leave that little detail out, this story makes sense