Science and art collide in space images

What are we really seeing when we look at photos of planets and stars?

Sarah Lewin • February 21, 2014

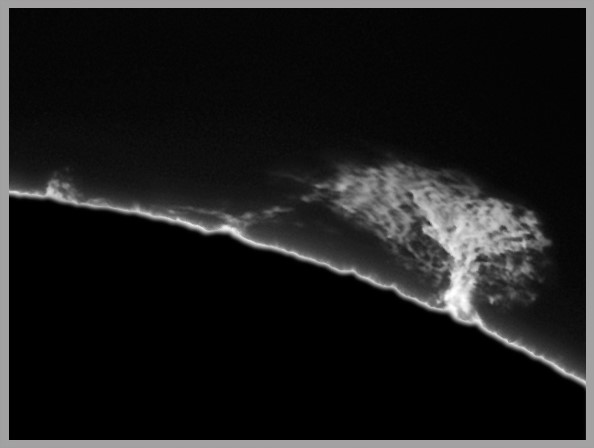

Space photographers make tough choices to ensure their photos are engaging while still reflecting reality, like this view of the sun’s edge [Image credit: Alan Friedman]

Photographer Alan Friedman ducks under a silver lamé curtain affixed to his telescope, hunching down to look through before attaching a video camera. His view is murky: Wavering atmosphere obscures the close view of the sun from his Buffalo, NY backyard.

He takes the images he grabs over the course of the day and feeds them into software that melds the clearest images into one. Then, Friedman often inverts the image to make it easier to see the details and adds color.

Meanwhile, 350 miles above, the Hubble Space Telescope orbits the Earth at more than 75,000 miles per hour. It points its mirror lens at what might be a distant galaxy and sends a black-and-white record of the photons detected by different filters streaming back to Earth, recording the molecular content and brightness. Afterward, image processors will choose the information gathered over weeks or months to incorporate into final composites, assigning each filter a color and brightness.

Whether they’re taken by backyard astronomers like Friedman or by NASA’s $2.5 billion marvel, pictures of outer space are not just a documentary of the earlier days of the universe. They’re also a set of artistic decisions showing what space would look like if only we had the eyes for it. Recent advances in lens, image processing and communication technology let professional astronomers and amateurs alike grab stunning shots of the skies and quickly share them with the public — but also generate the risk that over-processing or artistic choice might obscure the reality of what’s going on up there.

“Image processing is so powerful a skilled amateur can now obtain results that surpass all the big telescopes in the 70s,” says Thierry Legault, a French amateur astronomer and astrophotographer. “It’s like in the old times you had a horse, and now you have an airplane. Of course, you must learn to drive an airplane — and if you don’t learn to drive it, you can crash.” In this case, a crash would be a photograph where over-editing added details that weren’t there, or where artistic choices obscured the reality of a portrait. Today’s professionals and skilled amateurs must be incredibly careful to keep their images truthful as photographs of space.

But what, then, are photographs of space? First and foremost, they are data.

The first photograph to pierce Earth’s atmosphere — one of the moon — was taken in 1840 at New York University. Just five years later, French astronomers took the first photographs of the sun. Scientists quickly adapted photography as a way to do their astronomical research more precisely and standardize measurements of the stars — in other words, to record information about the sky that could be precisely measured later on.

“What the Hubble really produces is data that astronomers use to analyze and make their discoveries,” says Zoltan Levay, an image processor for the Hubble Space Telescope. “As a kind of a fortuitous byproduct, we can make nice-looking images.” Every day, Levay pores over the pictures generated by the telescope’s observations and chooses the ones that will make good photographs.

The Hubble dataset from each mission goes first to the scientists who requested it, but after a year it goes into a public archive where anyone can examine it and even make their own images.

Ray Villard coordinates the creation of photographs from the Hubble, and one of his pet peeves is when people complain that Hubble images are “too good to be true” or “over-edited.”

“Saying that you’re trying to glamorize the picture from Hubble would be like saying you’re trying to glamorize the Grand Canyon,” says Villard. He believes photos of space, like the Grand Canyon, are amazing enough without embellishment. “That said, there’s always some artistic judgment.”

The images that Hubble produces are rich with data, but they often don’t translate directly into the human visible spectrum. The basic photographs are in grayscale.

“You can never see the colors,” says Levay, “so the next best thing is to record those wavelengths” — the actual light that the Hubble is receiving — “and visualize them in a way that looks realistic but also conveys what’s inherent in that data.”

But the Hubble isn’t the only game in town. For the last 20 years, lenses have been cheap enough for amateur astronomers — sent to the sidelines after the 19th century, when observatories grew too large to be funded by individuals — to shoot vivid, professional-quality images of space. Software has improved too, allowing photographers to pick out the best frames in multiple exposures to edit out atmospheric blur.

Alan Friedman, the amateur space photographer, uses multiple filters to image his favorite target: the sun. One of his favorites is a hydrogen-alpha filter, which detects the distribution of hydrogen over the face of the sun and returns tremendous detail. But if he translates the wavelengths he records into the actual colors they represent, they’re a dull red that makes it very difficult to discern details. For Friedman, that’s where the artistic judgment comes in.

“What colors are fair to use?” he asks. “Does the sun have to be yellow? It’s all about making the images evocative.” Friedman pioneered a method of inverting images of the sun — making the light patches dark, and the dark patches light — to reveal more detail. Brighter structures on the surface of the sun are clearer when inverted to be darker than the surrounding area.

“I don’t think of it as a scientific image,” says Friedman, “but it’s definitely a documentary photograph — I’m not making up the details; the details are there and I’m trying to tell an accurate story.”

Creating such highly edited photographs of space brings an inherent risk that photographers will rely too heavily on the processing techniques to create their images, or that they will make choices that muddy the actual features.

“It’s like the saying: ‘Garbage in, garbage out,’” says Legault, the French astrophotographer. “Sometimes people think they can compensate for defects during shooting by image processing, but it’s not possible.” In December 2013, Legault attended an internal workshop for Astro Image Processing, where astrophotographers discussed how to teach others to edit space photographs while avoiding these pitfalls.

Legault describes two categories of space photos: The ones of objects close by, where we know the basic optical appearance that the picture should match, and the ones of distant objects like nebulae where there is no base appearance — human eyes can’t see them at all.

In that second case, Legault wonders, “Where is the end of photography and the beginning of painting? It’s quite difficult to put a frontier between real photography and something that is artistic.”

Legault worries that the public doesn’t grasp the reality of space photos unless the photographic techniques are carefully explained. That becomes more important than ever as Twitter, Facebook and other social media make it easier than ever to distribute photographs to the public.

Technology has made space photographs easier to create, but social media has made them famous. Villard recalls a time when an observatory’s astronomers would sit up all night making 8-by-10 inch colored prints to give to the media after a significant event like the spacecraft Voyager II passing by Neptune. It became a ritual for journalists to line up at a photo counter to try and get pictures for the next day’s news.

Now, images from Hubble mingle with those from amateurs and other observatories on news and aggregator websites. They’re on screensavers and posters and CD covers and go viral on social media pages. If asked what space looks like, people are just as likely to point to their Facebook feeds as they are to NASA’s website. Observatories even rely on amateur astronomers to take wider images of the sky to complement the narrow views of mega-telescopes.

In the end, space photographs are a way for amateurs, professionals and their audience to discover space together. “It has democratized astronomy for the public,” says Villard. “There’s so much available that they can get access to immediately — we’ve been fortunate to treat the public as co-explorers in that sense.”

Refresh if you can’t see the slideshow above!