Is the brain hard-wired for pain?

Analysis of white matter sheds new light on chronic pain

Claire Maldarelli • November 4, 2013

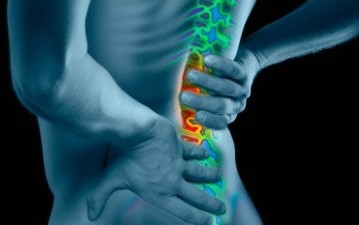

Researchers think some people may be predisposed to pain [Image credit: backpain.stanford.edu]

The last thing anyone in pain wants to hear is that “it’s all in your head.” But a new study, published this month in Pain, revealed that some chronic pain might, quite literally, depend on the state of the brain. Analyzing the brain structure of chronic pain sufferers may help explain why some people recover quickly from an injury while others experience ongoing pain. Researchers think these findings could lead to more specialized pain treatment.

Physical pain is one of the most universal forms of human stress. But not all pain is created equally. While acute pain is a temporary reaction of the nervous system to disease or other threats to the body, chronic pain is different. Signals keep firing in the nervous system even after an injury has healed.

“Everyone will experience acute pain,” explained Vania Apkarian, professor of physiology at Northwestern University in Chicago and senior author of the study. “But only some develop chronic pain and until now, no one understood why.”

According to a recent report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), an organization associated with the National Academy of Sciences, chronic pain affects nearly 100 million Americans. That’s more than heart disease, diabetes and cancer combined.

“While pain can be a symptom of another condition, when it becomes chronic, it can be a disease in its own right,” said Sean Mackey, chief of Pain Management at Stanford University in California and co-author of the IOM report.

To figure out what turns acute pain into a chronic problem, Apkarian’s team scanned the brains of 46 patients with lower-back pain using diffusion tensor imaging, a type of MRI that traces the brain’s white matter – fibers that transfer information to different places in the brain. The team then measured the fractional anisotropy (FA) – a reflection of the diameters, densities and other properties of those white matter fibers. They found that patients who developed chronic pain had decreased FA values compared to those who didn’t. Apkarian says these differences may make those patients more likely to develop chronic pain.

As patients recover, “the white matter measurements do not change significantly, suggesting these properties predict chronic pain and are not modified by the injury,” said Andy Alexander, director of the Waisman Lab for Brain Imaging at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

The researchers then compared the brain scans of the patients who developed chronic pain against a separate group of patients with already established chronic pain, and found that their white matter was similar. On the other hand, the white matter of healthy control subjects looked more like that of the subjects who did not develop chronic pain. After the study was completed, the researchers used the brain scans to retrospectively predict, with an 80% success rate, which patients in the original study would develop chronic pain.

Stanford’s Mackey thinks the key to resolving chronic pain is to understand how it develops. “Because many chronic pain problems start with an acute pain episode,” he said, “identifying factors that predict chronic pain will help develop treatments to prevent that occurrence.” Apkarian’s team is currently using the information gained from this study to develop new medications to stop the transition from acute to chronic pain.

“For fifteen years I had been advocating that the brain is important in chronic pain,” Apkarian said, “but I had no idea it was this important.”

3 Comments

Researchers like Apkarian go where the money is and since biomedical research has done a particularly poor job of identifying diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers for pain they now turn to brain signals since there other research is mostly a failure. There is a likelihood that brain research will also fail- lets not forget we already had a decade of the brain in the 90’s where NIMH Director Dr Judd said the decade of the brain will conquer mental illness by the year 2000-and so history repeats is repeating itself in the works of Apkarian- who goes where the money is for research.

Pain Mechanism: First ever explanation of how the mechanism of pain works in the brain

http://www.whatismind.com/PainMech.aspx

To blame the brain as responsible for pain is like the tail wagging the dog. And this research has resulted from teh failure to find predictive biomarkers for common conditions like low back pain that is not discogenic and osteoarthritis. To claim that pain is in the brain is to travel down a dangerous road where pathology outside the brain is ignored whilst doctors focus on altering the brain to change the perception of pain in the tissues. But science for some time has sought to numb pain rather than successfully find and fix what underlies chronic pain.