Amber Alliger’s guide to using a lab rat

A CUNY researcher studies how a rat’s environment can affect experimental results

Krystnell A. Storr • December 30, 2013

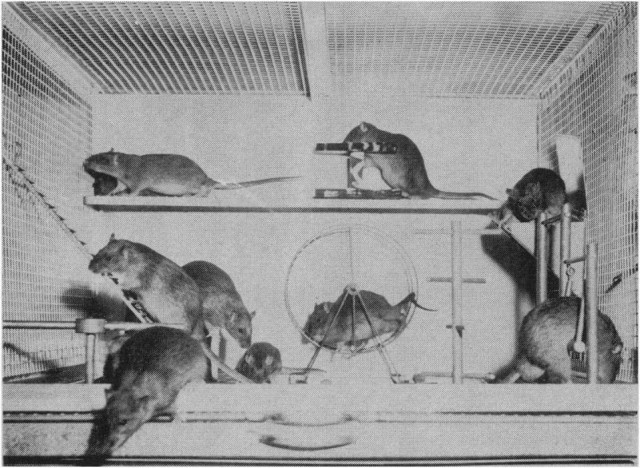

Alliger proposes we enrich the environment of experimental rats to produce data that is more accurate. [Image credit: Creative Commons]

In a university lab on the Upper East Side of Manhattan is a suburb where only rodents live. Plastic containers line the wall of a room like little boxes made of ticky-tacky — little boxes all the same. Several times a day, Amber Alliger, a petite woman with dark brown hair and eyes, goes on neighborhood watch.

Alliger makes the rounds to ensure that all the furry residents are living according to the rules of her experiment.

Alliger is a behavioral neuroscientist at the City University of New York’s Hunter College. For her latest research, she places a rat at one end of a star shaped metal platform, hides a bit of maple flavored oatmeal at another and observes how well the rat uses its memory to find the treat. She is studying the development of the rat’s brain cells, hormones and muscles, and aims to demonstrate that rats living under uniform laboratory conditions show reduced development. Alliger hopes to establish a set of guidelines to keep experimental rats in an environment where they are constantly stimulated and challenged to use their brains in different ways, duplicating the kind of variety that humans experience.

“Every human does not exercise, eat the same food or live in the exact same environment,” says Alliger. She explains that sometimes the success of an experiment is defined by “internal validity” in the data. This comes from lab work that is produced by running an experiment repeatedly on the same kind of test subject. It will often produce very strong and compelling results, the kind that a careful scientist is after. But when these data are used to create a drug for a diverse human population, the results can be disappointing. The data’s “external validity,” or applicability outside the lab, often plummets. “I’m not surprised that there are pharmaceutical companies facing multimillion-dollar lawsuits because of bad data,” she adds.

Alliger believes that experimental rats need variety just as humans do. “They are smart, social and inquisitive, just like us. So forget the barren environments where they can’t use any of the muscles and hormones and neurotransmitters that make them such great models.”

To protect these unique test subjects, Alliger suggests “enrichment protocols.” “Exercise changes the brain the most,” she says. “If you stress an animal and give it exercise, they do better the second time.” Rats can be enriched environmentally, for example by placing a spin wheel in their cages, or socially, by allowing them to live with other rodents. Regardless of the approach, Alliger believes researchers need to consider keeping their test subjects engaged in their own daily lives.

Alliger has a dedicated research team and colleagues that share her viewpoint.

“We love rats here!” says Sarrana Belgrave, another behavioral neuroscientist at CUNY. Belgrave, who has known Alliger for 10 years, recalls her favorite anecdote about her colleague. “Amber was wearing a bright yellow SpongeBob T-shirt, holding a rat and just smiling. She is the epitome of the creepy scientist girl that lets rats crawl all over her,” she adds fondly.

Alliger, 45, readily admits that although she was always interested, she came somewhat late to science. In high school, she was far from being the star science student. Although interested in the subject, she says, “Science used to scare the crap out of me.” As an undergraduate at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City, Alliger studied photography. She then enrolled in the Parsons School of Design in New York City, where she took up advertising. Alliger didn’t like having her creativity “controlled by clients,” so she decided at last to follow her interest in science.

She went back to undergraduate school for a third time, this time at Hunter College, where she majored in neuroscience. Alliger continued her graduate studies in animal behavior. Peter Moller, a behavioral scientist at Hunter College and Alliger’s graduate adviser, describes her as a scientist with “unbounding curiosity and uncompromising work habits.” He says she cares deeply about the welfare of the animals she is working with. “Amber is always concerned about the health of her research subjects. Her dictum is ‘unhealthy animals yield flawed science.’”

While a student at Hunter, Alliger served as a representative on the college’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). She reviewed applications submitted by the university’s researchers wanting to use animals as part of their study. IACUC makes sure animals are treated humanely and that the highest ethical and scientific standards are maintained throughout an experiment. Alliger noticed that some researchers were using their test subjects in illogical ways for instance, using a blind rat on a maze designed to test for vision. “That’s when I decided, here’s what I want to do: I want to better the science,” says Alliger.

But Alliger never lets her devotion to the welfare of her subjects get in the way of improving her scientific method. In fact, it’s the science that drives her.

After running a variety of memory tests on them, she will have to study their brains to get an accurate idea of how their development has been affected. This means killing the rat and removing the brain from its head. She can sacrifice her scaly-tailed residents in the name of science, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t difficult for her.

“If I can take out just a few brains and use them to show that all animals should be enriched, that it’s important, I think it will be worth it,” she says.

It’s not uncommon for researchers to give names to their test subjects, but for the memory experiment, Alliger has simply numbered them 36 to 48.

As she speaks, number 45 rustles in his box, pointing his sniffing nose toward the top of the cage. Soon, his brain will be removed, and studied. It becomes abundantly clear why, in her lab, Alliger prefers not to give them names — only numbers.