The fashonista physicist

Theoretical physicist Ágnes Mócsy teaches art students science

Rebecca Harrington • February 11, 2015

Mócsy heading to film at the Smithsonian in 2012. [Image credit: Ágnes Mócsy ]

The words SCIENCE, CREATIVITY and EXECUTION were written on the blackboard. Art students came up one by one, presenting their videos, paintings and songs about the astronomy they had learned in Ágnes Mócsy’s class at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. “You know that you’re better off if you have questions for each other,” Mócsy warned the class in order to encourage participation as she critically assessed one student’s poem about the formation of stars and planets. She seemed tough, but a slight smile gave away her delight with what the students had produced.

This mix of art and science is indicative of how Mócsy, a theoretical physicist, lives her life. Born during the 1970s as a member of the Hungarian minority in the Romanian dictatorship, her world today explodes with expression through food, fashion, cycling and her research into the origins of the universe.

At the start of her career, Mócsy was on the path to her dream job. She had been offered a tenure-track professorship at a top research university. Before she accepted, however, a tiny ad caught her eye for a physics teaching job at Pratt — best known for its curriculum in art, architecture and design. Mócsy was always interested in art, but she was worried this path could be “career suicide.” But since she took the job at Pratt in 2008, Mócsy has become a self-described science ambassador, working to get more people interested in science through art, at pubs, in movies and by teaching it to artists every day.

Carole Sirovich, chair of Pratt’s math and science department, said she was impressed by Mócsy’s sharp intelligence. “She’s such a high profile researcher who does fancy nuclear research,” Sirovich said. “I thought it was a coup that I could get her.”

Mócsy’s astronomy class actually has a waitlist, but not because it’s easy. Pratt senior Alexandra Borrelli said Mócsy “has a reputation for being a tough grader, but everyone wants to take her class anyways because she’s so passionate.” Borrelli, a graphic designer, is taking an independent study course with Mócsy this spring. Mócsy said she’s picky about the students she decides to mentor because she has little spare time. She spends nine hours each week teaching (not including office hours, grading or research), leaving little time for her many hobbies, which include cooking 15-course vegan birthday dinners for her friends. “Work is like a gas,” she said. “It expands to all the space you have.”

She’s always thrown herself into her work. Mócsy got into Babes-Bolyai University‘s competitive physics program in Romania in 1989 despite a government cap on the number of ethnic Hungarian students. Her single goal while growing up was to get out and see the world. But to do that, her mother said, she would “have to use [her] brain.” As one of the top three students in her undergraduate class, Mócsy received stipend checks for her good grades. She spent the first one taking her parents and brother out to dinner, a luxury at the time. And the next two checks bought her first pair of fashionable shoes: velour brown pumps with a chunky, round heel and coppery lining. At the time, it was a daring purchase. That first acquisition grew into a 240-pair shoe collection, which is tucked into every crevice of her Brooklyn apartment.

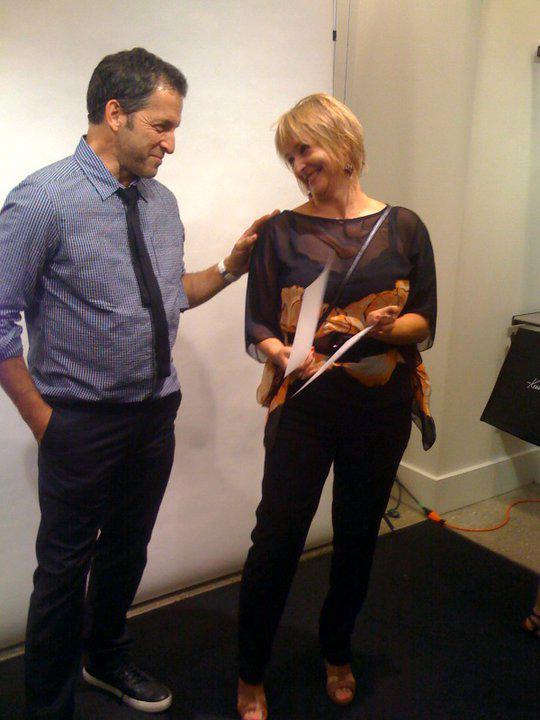

Mócsy explains Schrodinger’s equation to fashion designer Kenneth Cole in 2010. [Image credit: Ágnes Mócsy]

By then, however, she was already a well-respected physicist noted for her research on quarkonia: particles that are “golden signals” in heavy ion collisions indicating the existence of quark-gluon plasma — the primordial soup of subatomic particles that existed at the beginning of the universe. After receiving her PhD in theoretical physics from the University of Minnesota in 2001, Mócsy did research at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen and was an Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellow before Brookhaven National Laboratory hired her as a researcher in 2005. There she worked on the theoretical team at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider. Longtime friend Paul Sorensen, a fellow physicist at Brookhaven, said some of Mócsy’s nuclear physics papers, including those on quarkonia, are still among the most advanced in the field.

Watching the field deliberate over which theory should be accepted made Mócsy appreciate how science is a process, filled with pitfalls, passion, disagreement and delight, she says. She has since tried to communicate this human side of science to the public and to Congress, making multiple trips to Washington, D.C. to convince congressional leaders to support basic research funding.

Mócsy no longer has time to do as much research, though she still attends physics conferences, reads the latest research to keep up with the field and is unofficially affiliated with Brookhaven. She says she has some nuclear physics calculations she’s been meaning to solve sitting on her office shelf “getting dusty,” but as an art school professor Mócsy doesn’t have a lab full of graduate students to do the calculations for her.

Yet one benefit of teaching at Pratt, Mócsy said, is unearthing a passion for science in her students that they may not have known they had. Mócsy’s former architecture student, Teiler Kwan, actually quit Pratt to become a physicist. Though Kwan said he had no interest whatsoever in science, from the first day in Mócsy’s astronomy class he was enraptured by the way she explained scientific concepts in a way his previous teachers never had. He just graduated with a physics degree from the University of Oregon, and plans to get his PhD in astronomy. “She’s always been kind of a role model to me,” Kwan said. “She’s a very powerful force in my life.”

Mócsy comes off as self-assured, but says she doesn’t feel this way on the inside. In reality, she is constantly “double guessing” herself. Before giving a talk, she gets so nervous that she feels faint and forgets what she’s presenting. But the moment she hits the stage, she said, she nails it. Sorensen said Mócsy is such a perfectionist that she has a hard time enjoying her accomplishments. “When she has some success, she’ll immediately know how it fell short from what she was hoping it would be,” he said, “and her ambition means she immediately thinks of what should be happening next.”

Mócsy takes the beautiful things in life as seriously as she takes her science. On a recent fall day, sitting in a café near her apartment as the skies above New York City unleashed an onslaught of sleet and snow, she was as fashionable as ever in a faux fur sweater and leopard print gold earrings. Her iPhone, tucked into its black case shaped like a kitty, pinged with email notifications about the upcoming science themed art exhibit she was curating at Pratt, the film she was directing about the process of science and plans she was making with friends. Sipping her tea with just a touch of sugar, she thought back on how her career choices led to a role she never envisioned for herself.

“I used to think I was taking the road less traveled,” she said. “But then I realized, I’m making the road.”