Bio-inspired soft robotics are making a splash in ocean research

A squid robot is among the latest to take to the seas

Casey Crownhart • March 17, 2021

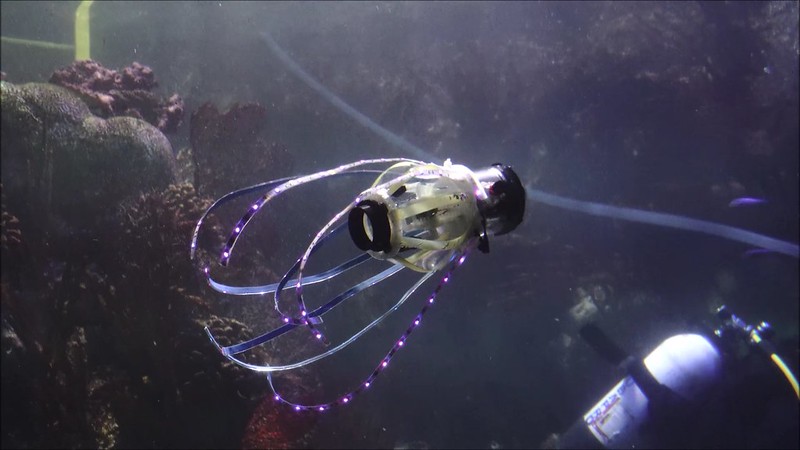

The squidbot joins other ocean robots that are increasingly being tested outside the lab. [Credit: UCSD Jacobs School of Engineering | CC BY 2.0]

It’s a squid, it’s a fish, it’s an … underwater robot?

New bio-inspired robots with soft, flexible parts might have the superpowers required to tackle the contemporary challenge of exploring and conserving ocean environments. Unlike their predecessors, such as the human-piloted Deepsea Challenger or the remote-controlled Hercules, these stealthy bots could navigate delicate environments by squishing into tight spaces, blending in with their surroundings or just treading lightly.

With the health of the world’s oceans and marine life under significant threat from overfishing, warming seas, acidification and plastic pollution, new soft robots could someday help biologists and ecologists learn more about the health of these habitats and their inhabitants, informing efforts to save coral reefs and other ecosystems.

One of the latest soft-bodied explorers to splash onto the scene — a squid-like robot appropriately called the squidbot — was described in a paper published in December 2020 in Bioinspiration & Biomimetics. The squidbot joins the ranks of other bio-inspired soft robots to be tested in realistic environments, like SoFi the fish-bot built at MIT and a chimeric crab-octopus robot from The Biorobotics Institute in Italy.

“I’ve always been excited about robotics as a way of solving a lot of fundamental problems,” says Michael Tolley, a mechanical engineer from the University of California San Diego whose team recently developed the squidbot.

Last year, Tolley’s team took the squidbot for a spin at the Birch Aquarium in San Diego. The robot moves much like real squids, whose soft bodies are key to their efficient locomotion in seawater. They expand, pulling water into their bodies, then they contract and push it out, like an umbrella closing, allowing them to pulse through the water. The squidbot relies on these same jets of water to navigate the environment, and Tolley says that it is the first robot of its kind to use this same mechanism to swim continuously.

This mode of locomotion could be useful in designing soft robots that can move around efficiently underwater while also being able to squeeze into tight spaces, like coral reefs. “The idea of a squid is very appealing, and I think it’s a natural progression of understanding,” says Robert Katzschmann, head of the soft robotics lab at ETH Zurich in Switzerland.

Katzschmann has been working on soft robotics since his PhD work at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he created and demonstrated the SoFi fish robot. He and his team have big plans for soft-bodied fish robots, Katzschmann says, some of which could dramatically alter the field of ocean exploration.

In underwater ecosystems, propellers and unnatural movements can disturb wildlife, skewing researchers’ view of what’s going on, Katzschmann says. Soft fish robots may allow biologists to go into unexplored spaces where other robots can’t, wiggling their way through mats of algae in the Sargasso Sea or integrating with schools of fish swimming amidst coral reefs.

With all of his lab’s ocean-going efforts, the central idea of bio-inspired robots for Katzschmann is to help researchers blend in and “be able to go underwater and act like [they] are a member of the society in the water,” he says.

Tolley says his team is trying to learn more about how nature solves problems in the ocean, so they can emulate it. His group in San Diego is working on a variety of bio-inspired robots, like a starfish-bot with many small legs on the bottom to crawl across the ocean floor and a clingfish-bot that can attach to rough surfaces.

The team isn’t trying to create the Madame Tussaud’s of the deep. Rather, Tolley says he wants to know: “What are some of the exciting capabilities that we see in nature, and what can we understand about how they work?”

And combining these exciting capabilities is what Marcello Calisti, a roboticist at The Biorobotics Institute at Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies in Pisa, Italy, aims to do. His work shows what researchers might dream up once they have a menu of nature-inspired technologies to choose from.

Calisti’s team unveiled a walking underwater robot called Silver2 in research published last May in Science Robotics. The robot includes flexible parts in its joints — like those found in crabs — that help it crawl along the uneven terrain of the ocean floor.

The team also recently added a soft gripper arm that was inspired by the group’s previous work on an octopus-inspired robot. The result is a sort of chimera, a crab-octopus robot that can navigate the ocean floor and gently lift biological samples or clean up plastic pollution.

Calisti says researchers should take some liberties when building nature-inspired robotics. Instead of blending in with the ocean’s residents, he wants to mix together nature and human-made design to make robots that can serve a new purpose.

Bio-inspired soft robotics have a way to go before they become truly useful for research. But for scientists looking to preserve and protect oceans, the oceans themselves might just hold the key.