Ancient ocean sediment carries a dire warning for modern climate

Climate change sped up the collapse of the Mayan civilization, but our climate is changing even faster

Maiya Focht • December 17, 2021

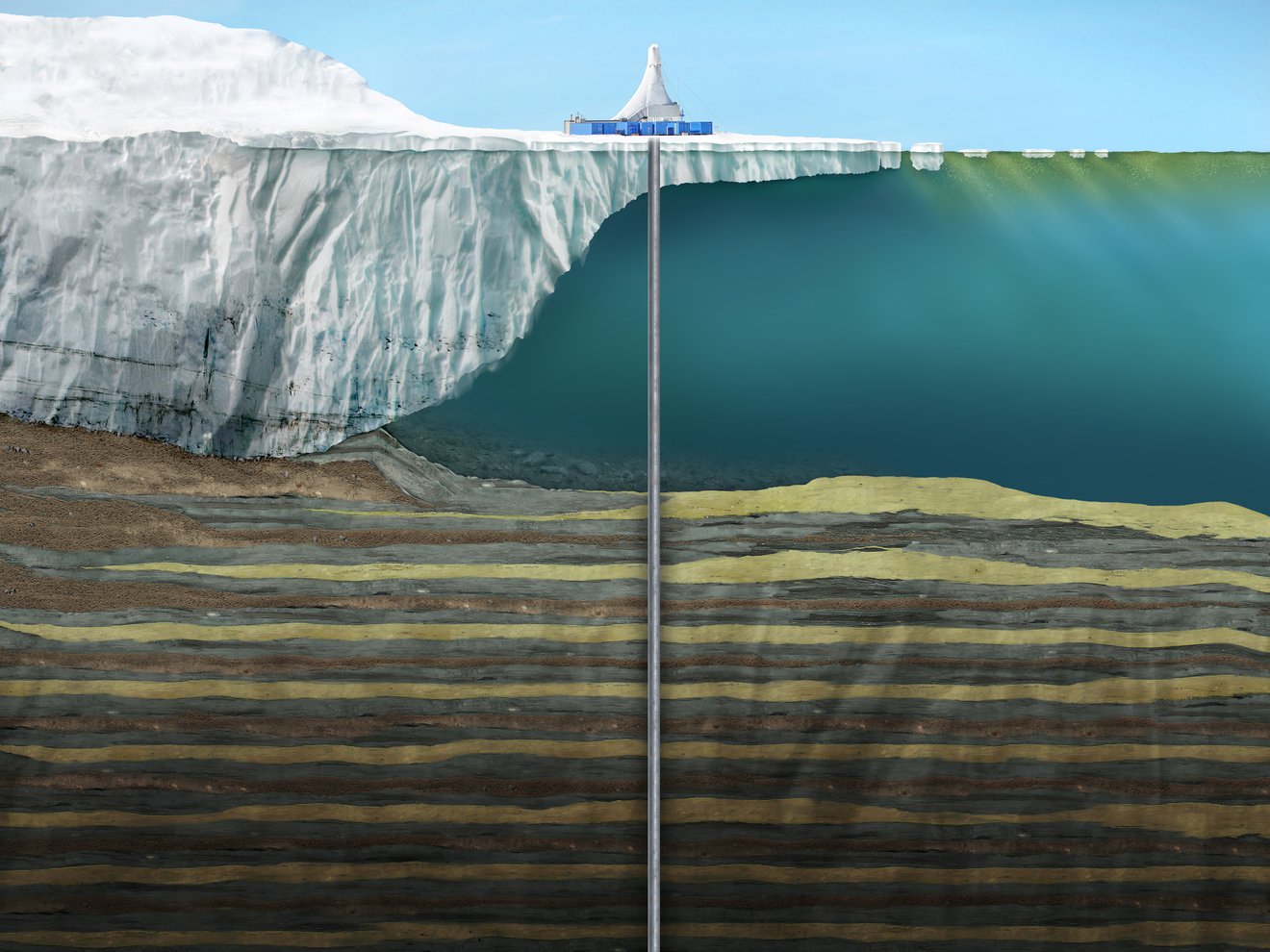

Core samples of ancient sediment are harvested with drilling operations like this rendering from a NASA study on Antarctic warming. These cores can give researchers a detailed picture of past climate change – and a warning for today. [Credit: NASA | CC BY 2.0]

Thirteen hundred years ago, one of the most advanced civilizations of the ancient world flourished in the jungles of Central America. Over the next century, however, the great cities of the Maya were abandoned one by one, as the population struggled with devastating drought and deforestation.

What happened? Archeologists combing through Mayan ruins in Guatemala and Mexico have suggested that warfare and overpopulation were factors, but some of the most compelling evidence of what went wrong for the Maya — and what’s going wrong for us today, too — is actually thousands of miles away, buried deep beneath the Antarctic seafloor.

By studying the chemical composition of long-buried sediment and ice, researchers have discovered that a period of sea warming coincided with the beginning of the collapse of Mayan civilization around the year 800, according to Stephan Pekar, a paleoclimatologist at Queens College, City University of New York.

“The severe droughts contributed to Mayan collapse — absolutely, period,” Pekar says. “The events in Antarctica, the climate events, teleconnected the whole world. Atmospheric systems are connected; it’s beautiful.”

It’s also scary, because Pekar, who spoke this November at a discussion at New York’s National Arts Club, made clear that today’s warming trend is happening 10 times faster than anything the ancient Mayans had to deal with. The global temperature rose about 1 degree Celsius over the last 100 years — compared with just one-tenth of a degree in the ninth century.

“We’re changing [climate] faster than any time since 65 million years ago. And what happened 65 million years ago? Does anyone want to shout it out,” Pekar says, addressing the audience. “A big asteroid hits the earth, wipes out the dinosaurs. And let me let you in on a little secret guys: it wasn’t the dinosaurs’ fault that the asteroid hit.”

Researchers can make those comparisons with confidence because of a quirk of physics: Like very old library books, bubbles of air trapped in long-buried ice and sediment are a retrievable archive of ancient atmospheric conditions. By drilling down thousands of feet and extracting core samples, scientists can analyze the chemical composition of the air inside those bubbles and see what the climate was like at the time they were formed. And if they extract sufficiently long cores, they can even see how conditions changed over thousands of years.

For example, in the cores Pekar studied, collected from below the Arctic seafloor, he explains how different concentrations of oxygen and fossilized cells created distinctive grey and green stripes throughout the core, like tree rings spanning an 11,000-year period. These stripes, he says, revealed a period of Antarctic sea warming occurring at the same time the Mayan civilization began to collapse under pressure from drought.

Paleoclimatologists have been scrutinizing ancient cores for between 50 to 100 years now and the chaotic picture of past climate that has emerged from the data is especially disturbing in light of our current crisis, according to Carrie Morrill, a geoscientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “Climate doesn’t necessarily change in linear and predictable ways,” she explains. “It can change in surprising and unexpected ways.”

Though there are distinct differences due to industrialization between historic climate events and our contemporary predicament, we can still learn a lot of lessons from Earth’s history, says Scott Wing, a curator of paleobotany at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. “One of them is that really rapid warming events can be very difficult for life. Another lesson is that you probably shouldn’t go around thinking that it’s the end of the planet,” he adds.

Pekar says the message in the ancient ice and sediment is clear: The world must act now to avoid the fate of the Mayans and head off the most drastic climate disruptions. The challenge is monumental, but Pekar takes heart in the activism he sees every day. “Don’t give up,” he says, “there are so many people out there in the world fighting this and being successful.”