Killing with grace, dying with dignity

How I found a community where all my best friends are liars

Kohava Mendelsohn • January 26, 2025

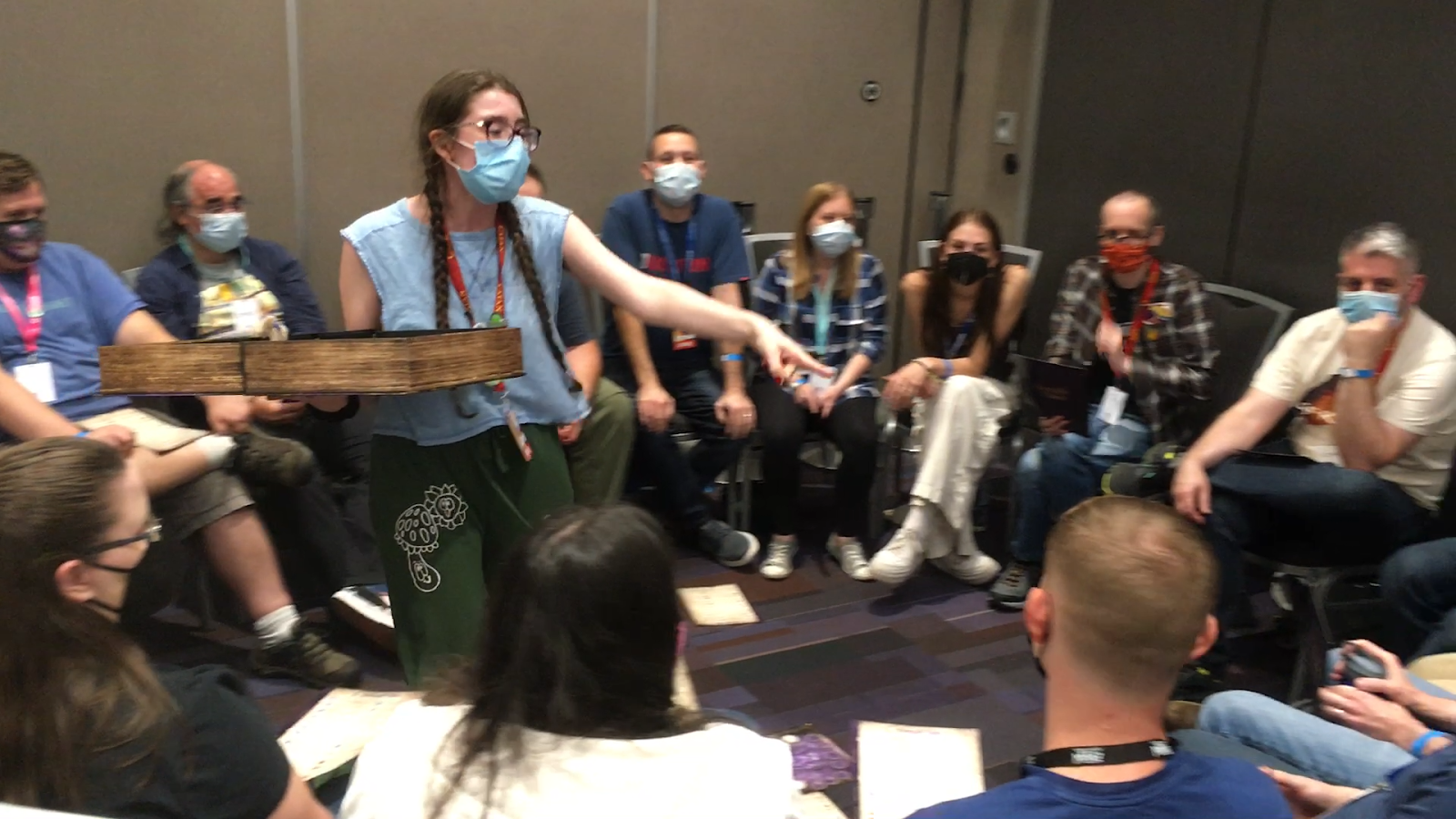

The story contained in a roll call at the end of a game of Blood on the Clocktower brings the players closer together. [Photo Credit: Kohava Mendelsohn]

On an otherwise peaceful night in the intimate village of Ravenswood Bluff, I was awakened by a scream. I gathered with the other townsfolk beneath the old clock tower in the town square only to find our beloved town storyteller, limbs splayed unnaturally across the hands on the clock, blood dripping down from a demonic wound in their corpse.

A game was afoot.

Somewhere in this town was a demon, which the good townspeople had to reveal and execute before we perished one by one. When anyone around you might be secretly evil, whom can you trust?

I have heard this setup read aloud hundreds, possibly even thousands, of times, as I begin new games of Blood on the Clocktower. Originating as my “COVID hobby,” this social deduction game quickly cast its spell on me. Though it began as a board game, it was quickly adapted to an online game as well, with an accompanying app. But my dedication is not to the game alone. It’s the community around the game that has kept me playing again and again.

So how did some of my closest friendships stem from a game of deception and betrayal? The very nature of the game is antagonistic, competitive and deceitful — or is it?

When I first discovered Blood on the Clocktower, I was drawn to the logic puzzle of the game. A minority of players, who all know each other, play on the evil team and a majority are on the good team and start the game knowing nothing. Over the course of the game, each player’s special role will allow them to gain information to piece together who is good and who is evil.

But I was also drawn to the social element of the game. If you’re evil, you have to lie and pretend to be good in order to win. If you’re good, sometimes you are encouraged to lie in order to not get killed by the evil team (every night, the demon kills, depriving someone of their special power). You might be familiar with this style of game if you’ve ever played Mafia or Among Us. I was a theater kid in high school and love improv. Lying in a game of Blood on the Clocktower scratches the same itch that acting does for me, getting to pretend to be someone I’m not.

In January 2020, I discovered a Discord server where games of Blood on the Clocktower regularly took place, and all I had to do was ask to play. I was scared. I didn’t know anyone, and had never played the game before. It took me six months to join my first game.

When I finally did, I think I lost — I don’t quite remember — but I know I was exhilarated. My brain was working rapidly to keep track of everything. About half the players in my first game I am still friends with to this day.

My experience isn’t unique. Plenty of players I’ve talked to are on the shyer side, initially intimidated by the social element of the game. “The game scared the shit out of me. I used to be so socially anxious,” recalls Michelle Wijma, a writer from Groningen, in the Netherlands, and a regular on the game company’s official Blood on the Clocktower livestreams.

This is part of the magic of social deduction games — they create frameworks for structured social interaction. Socially anxious and neurodivergent people both benefit from structured social activities. In Blood on the Clocktower, the game is divided into sections: night time, where everyone closes their eyes and receives secret information; whispers, where people have private conversations; and executions, where everyone gathers together and discusses information in public. Knowing I can always discuss the game when at a loss for conversation topics and that I am working with other people towards a clear goal helps me feel more comfortable meeting and talking to people I’ve never played with before.

The “playing pretend” aspect of Blood on the Clocktower may also play a part in the bonds it creates. Improvisational theater reduces social anxiety through engaging people in collaborative creative tasks and exposing them to uncertainty, a 2019 study found. There was also some evidence that the experiments made people feel closer to one another, according to Peter Felsman, a social worker and lead author of that study.

In social deduction games, especially Blood on the Clocktower, there are the same elements of working together creatively and being willing to accept uncertainty. If you’re on the evil team, you have to pretend to be someone you’re not (a good player) and work with your team to construct a false narrative of the game. I hate lying in real life, but I love lying in Clocktower.

Accepting uncertainty means entering the game knowing you might lose. I might trust the wrong person, or make a mistake, and that’s part of the game. “That possibility of failure in a safe environment is something that adults don’t usually get, but you get it in this game and that’s why this is such a great bonding exercise,” says Agnieszka Przepiórkowska, a regular moderator on official Blood on the Clocktower Twitch streams.

Blood on the Clocktower also has built-in mechanisms for inclusion and group bonding, some obvious and some more subtle. At the start of the game, the moderator (or Storyteller, in game lingo) introduces the rules. After going over the basics they mention four more things: You can say anything at any time, the Storyteller is a neutral entity, don’t cheat, and rule four: “kill with grace and die with dignity,” or, as it’s colloquially known, “don’t be a dick.” These rules help form the social norms for the rest of the game.

In communication theory, there are five stages to how small groups work on a given project: forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning, according to Shane Tilton, a professor of Multimedia Journalism at Ohio Northern University. Tilton has used social deduction games to model the process of small group communication for students, saying they simulate those five phases well.

Forming is pretty self explanatory — the group comes together, the game begins. Storming is where the conflicts occur and are hashed out. In many groups or games this is the make or break time: if a group makes it through the storm, they are solid. Given that in Blood on the Clocktower, the Storyteller is a conflict mediator and “be nice” is a core rule of the game, it is set up for the players to weather the storm.

The norming phase is when a group comes together after conflicts are resolved. Through conflict, the group has established how they are going to work together. This is the stage when metas may develop, unofficial rules of play that a group creates when playing together. They can be things like “don’t execute new players early,” “always skip an execution when four players live,” or “don’t talk about the game during the night phase.”

Metas can help players bond, but may also impair community creation, according to an undergraduate thesis on the philosophy of gaming by Julia Williamson for the University of Vermont. Metas can become inside jokes, and lead players to care about each other on an individual level, not just in terms of the game. However, they can also create feelings of exclusion if a player entering the group is unaware of the meta or feels their agency is being taken away.

In Blood on the Clocktower, there is immense support for player agency. I’ve heard from the game designers themselves that they intend for each secret role to have multiple viable strategies. For example, roles with powerful pieces of information can share it all immediately, or keep it secret and see if anyone contradicts it, catching them out. There are many ways to play the game, which helps to break constricting group metas.

After norming, the small group then performs the task (completes the game), and adjourns (says their goodbyes). Right as the game ends, Blood on the Clocktower has another special feature: the Storyteller then “tells the story” of the game, revealing each player’s hidden role and highlighting exciting moments from the game.

This story helps bridge the gap between a competitive game and a fun shared experience. Sharing out-of-the-ordinary experiences can help people feel closer, so turning the game into a shared story helps it feel less competitive. Some of my favorite games are ones I’ve lost, as they tell a compelling story. Perhaps the Slayer (a character with one chance the whole game to pick the demon) accurately selects their target and wins, or the Monk (a character that protects a player each night from dying) saves three people in a row. In Blood on the Clocktower, “if you do a cool thing, people will tell the story for the next six months,” says Jessica Lugo, a community member from New York.

And after telling each other these stories over and over, resolving our conflicts through game-implemented solutions, and using the framework of the game to feel comfortable with each other, we’ve become a community. “A lot of times people think that there’s just some kind of invisible wall that makes games different, or makes online different, but the psychological mechanisms that play here are really the same as your local team or club,” says Dr. Rachel Kowert, a psychologist who studies online gaming communities.

As I pack my bags to head off to Pax Unplugged this year, I’m not most excited to play some Blood on the Clocktower, though I’m sure I will for hours and hours. No — it’s seeing my friend who gives the coziest, kindest hugs, another one who took time to check in on me when my community was in crisis, and the people who send me daily pictures of their lives, from all across the world that excites me the most. United through a love of lying, puzzles, and probably a few psychological mechanisms, this community is one I know I’ll have for the rest of my life.

2 Comments

This narrative helps bridge the gap between a competitive game and an enjoyable shared experience. Since sharing unusual experiences can foster a sense of community, transforming the game into a shared narrative makes it feel less competitive.

This article beautifully captures how structured social games like Blood on the Clocktower build community through shared narrative and deduction. It reminds me of the strategic engagement in tower defense games. For instance, PokemonTD offers a similar blend of strategy and theme, where managing your team against waves of enemies provides a compelling, goal-oriented challenge that fosters focus and enjoyment.