There’s a three-minute video that can change the way you die. It shows a group of doctors crowded around a mannequin, pushing down on its chest, placing a tube down its throat. It cuts to an unconscious elderly person in a hospital bed, tethered to machines by the mouth and the veins. “Frequently, CPR does not work,” the female narrator calmly explains, and those who survive are often sedated through IV and placed on a ventilator which prevents eating and talking.

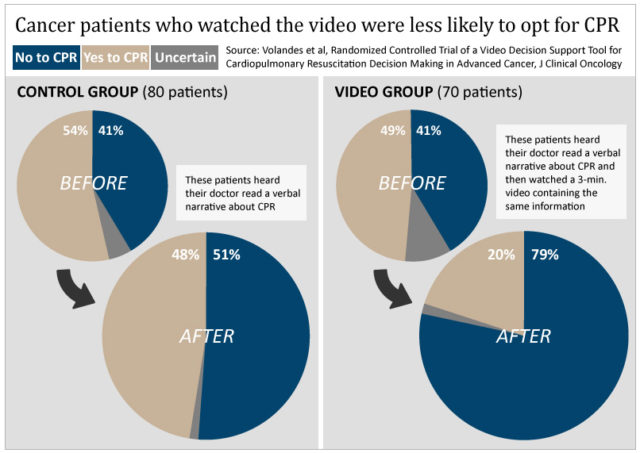

Advanced cancer patients who watched this video in their oncologists’ office were over 50 percent more likely to say they did not want CPR attempted on them, compared to a group of similar patients who heard only a verbal version of the same information. The study, published in January in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, is the latest in a string of trials led by Angelo Volandes examining how informational videos influence patients’ preferences about treatment at the end of life.

The notion that people are entitled to opt out of potentially life-saving care is only a few decades old and still stirs emotions, as evidenced by the noxious controversy that pushed funding for advance care planning out of the 2010 federal health care reform law. Among health care professionals, however, there’s little debate that too many patients nearing the end of their lives are getting aggressive treatment that does more harm than good. A quarter of Medicare’s ever-increasing costs are from treatment in the last year of life, excluding prescription drugs and nursing home care. Volandes, an internist at Massachusetts General Hospital, doesn’t talk much about money, though. He says he wants to empower patients to make informed decisions.

The idea of using visual aids came to Volandes early in his career. A first-year resident at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital, he was admitting a middle-aged patient whose fate had long been sealed by cancer, and he asked what she wanted them to do if her heart stopped beating. But as he described procedures like cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intubation and ventilation, he could tell she was unfamiliar with her options. She needed to see for herself.

Volandes took the patient and her husband on a tour of the intensive care unit, something he later learned he was not supposed to do. She saw first-hand how medical technology could be used to prolong life, and weeks later, she died in her home, having chosen not to spend her last days in a forlorn battle for more time.

Volandes had found his mission. “That’s when it occurred to me that we could recreate this tour to better inform our patients and their families about their options, especially at the end of life.”

For the better part of the last decade, Volandes, who studied filmmaking during medical school, has been producing short videos to inform decision making about end-of-life care. With funding from the federal government and the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making, Volandes and other doctors have tested the videos in controlled studies, and they have been integrated into standard practice at 35 large health care organizations in the U.S.

The results of the studies are remarkably consistent. In each of nearly a dozen papers trying different videos in different populations, including individuals not currently facing illness, the videos turned people off of life-prolonging treatment. In fact, in four of the studies, not a single person said they wanted life-prolonging care after watching the video. Some of the videos include clips of CPR and ventilation contrasted with clips of a person receiving hospice care. Another features a condition rather than a treatment – it shows a woman with advanced dementia who cannot walk, communicate or feed herself.

Physicians asked to weigh-in on the studies appreciated the problem Volandes is trying to tackle, but some weren’t enthusiastic about using the videos themselves. “It may not be appropriate for most patients, frankly,” said Maria Silveira, who practices general medicine and palliative care at the University of Michigan Medical Center. She said that doctors who have established, trusting relationships with their patients wouldn’t need to use a video aid. “Really these videos came into being – this is only my opinion – for the purposes of helping people decide to refuse this care.”

To Volandes, the videos provide accurate images to patients who have no experience with intensive care or who may have learned misconceptions from the media. “Trying to recalibrate expectations of what these interventions do is part of the informational value of the video,” Volandes said. “Because everybody thinks that, you know, your doctor looks like George Clooney and the patient looks really good on a ventilator and they’re just going to stay on the vent for a day.”

A 1996 analysis of popular medical TV programs ER, Rescue 911 and Chicago Hope found that an unrealistically high 77 percent of patients who underwent CPR on the shows survived and nearly all of those survivors were either successfully discharged from the hospital or not shown again. The patients were mostly children, teenagers or young adults. Just a handful had underlying illnesses like heart disease or dementia.

Jeffrey Allerton, an oncologist and hematologist in State College, Pennsylvania, agrees that many patients have a misinformed conception of CPR. “You have to depress the sternum two inches. Now with the cartilage between the sternum and ribs, it’s flexible, but you’re going to be breaking ribs,” Allerton said. “And when you’re doing it, you can hear them, and you can feel them. People around you, even though they’re not actually doing the CPR, they can hear it happening.”

Although more than 40 percent of cancer patients undergoing in-hospital CPR survive the event, most never go home again. Only six in 100 cancer patients are actually discharged from the hospital following CPR, according to a 2006 meta-analysis of 42 studies. For patients with localized disease, the survival rate was higher: 9.5 percent, compared to 5.6 percent for patients with metastatic cancer.

Families that opt for CPR may be also setting themselves up for another difficult decision should their loved one survive and be placed on life support. “You think it’s hard for people to decide whether they want to be resuscitated or not? It’s even harder for a family to decide how long do we keep mom or dad on a ventilator,” Allerton said.

In a study of 332 advanced cancer patients by researchers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, those who received aggressive care in their final week were thought to have poorer quality of life by their family members than those who did not undergo ventilation, resuscitation or admission to the ICU. Six months later, the family caregivers of patients who received aggressive care were at higher risk of depression and were more likely to experience regret. More than 60 percent of the patients had not had a discussion with their doctor about end-of-life care. Standardizing advanced care planning is among the goals of Volandes and his group.

But even if the statistics still point to too much treatment rather than too little, the question remains whether the videos help each individual receive care matching their goals and values. Were the participants in the studies becoming more informed by the videos or were they having a visceral, emotional response?

Bob Arnold, an internist at the University of Pittsburgh, questions such a distinction between emotion and information. Our emotions, he said, help us determine what’s important. “It’s another data stream.”

Emotions may be information, but it doesn’t follow that they produce better decisions. “It’s not obvious that the vivid information that patients made their choice about is the information that ought to be used,” said David Pizzaro, a psychologist at Cornell University. His research has explored how the emotion of disgust can shape our choices and moral judgments.

“Showing women videos [of birth] may very well make them more likely to prefer anesthesia before they go into labor, because of the vividness of the video’s depiction of pain,” Pizarro added. “But the question of what they ought to do is not clear.” He noted that men who watched a video of an amorous couple considering unprotected sex placed less priority on using a condom than did those who read a text description of the scenario.

There are some procedures, like a hip replacement, that you wouldn’t want a video for, said Peter Ubel, a behavioral scientist at Duke University and author of Critical Decisions: How You and Your Doctor Can Make the Right Medical Choices Together. “That video might scare people away from a surgery that they might benefit from. But what Angelo has done is picked out several areas where most people in healthcare feel like people do too much. They ask for too much without knowing what that means.”

Volandes is sensitive to the notion that his videos could be manipulative. The clips clearly aim for an objective account of patients’ options and the visuals are mild when compared to real life. He noted that panels of clinicians and ethicists vetted the videos, and the vast majority of research subjects said they feel comfortable watching and recommending them to others.

Most importantly, Volandes said, we know the videos enable people to make better, more informed decisions because the patients who viewed them had higher scores on tests of knowledge about end-of-life care options, compared to the patients who only heard the verbal description. In the most recent study, subjects in the video arm scored an average of 3.3 out of four questions about CPR. The verbal control group averaged 2.6 correct answers.

Volandes’ studies are not well designed to assess knowledge, however. The primary outcome measured is patients’ preferences for types of care, not their understanding of those treatments. In the studies, the video group receives the information twice – once in a verbal narrative and again in the video – while the control group has only one pass at the facts. It’s unclear, therefore, whether the medium or the repetition accounts for the bump in knowledge scores.

“The reason why we never study the video alone is because the videos are never meant to be standalones,” Volandes explained. “The videos are meant to supplement, not supplant the doctor-patient relationship.”

Video is a powerful tool – it can help you teach and it can help you sell. The choices behind the content can profoundly impact the lives of patients and their families, and they are just that – choices.

Writing at ProPublica about his parents’ end-of-life decisions, health journalist Charles Ornstein said his father’s heart stopped beating last year and after reviving him with CPR, doctors said he was unlikely to make a full neurological recovery. In fact, “he was home within weeks, back to his old self,” Ornstein wrote. Such cases don’t appear often in real life. They don’t appear at all in Voldandes’ videos, and it’s not clear if they should. But what’s included in the videos becomes more salient to the viewer than what’s excluded, so it’s difficult to see them as a neutral source of information.

“It’s not neutral,” said Ubel. “But I don’t think that the words alone are neutral either. I don’t think we can find a neutral way to do this.”

2 Comments

Hi! I could have sworn I’ve visited your blog before but after going through a few of the articles I

realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m certainly

pleased I discovered it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back often!

As an RN of 40 years,I find this exceptionally interesting and wonder where this study is 6 years after this was written. During my 65 years I have moved several times. Currently outside of Phila. However 15 years ago I left this area and moved back to the small town where I grew up(around Gettysburg). I was getting a divorce but wanted to be closer to my parents in case their health deteriorated to prevent them going to a nursing home

When it came to discussing this with my folks,I was in awe that they had no idea.They were open to discussing end of life scenarios. Personally I think this is a Great idea when presented correctly and 1 on 1

Discussion with a knowledgeable caring person. However then you also have people like my ex-husband who wants nothing to do with death and dying or to face mortality and probably desires to allow others to make his decision for him